Excerpt

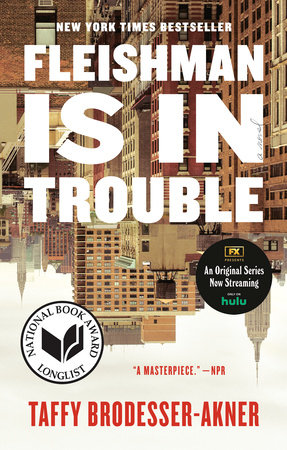

Fleishman Is in Trouble

Toby Fleishman awoke one morning inside the city he’d lived in all his adult life and which was suddenly somehow now crawling with women who wanted him. Not just any women, but women who were self-actualized and independent and knew what they wanted. Women who weren’t needy or insecure or self-doubting, like the long-ago prospects of his long-gone youth—meaning the women he had thought of as prospects but who had never given him even a first glance. No, these were women who were motivated and available and interesting and interested and exciting and excited. These were women who would not so much wait for you to call them one or two or three socially acceptable days after you met them as much as send you pictures of their genitals the day before. Women who were open-minded and up for anything and vocal about their desires and needs and who used phrases like “put my cards on the table” and “no strings attached” and “I need to be done in ten because I have to pick up Bella from ballet.” Women who would fuck you like they owed you money, was how our friend Seth put it.

Yes, who could have predicted that Toby Fleishman, at the age of forty-one, would find that his phone was aglow from sunup to sundown (in the night the glow was extra bright) with texts that contained G-string and ass cleavage and underboob and sideboob and just straight-up boob and all the parts of a woman he never dared dream he would encounter in a person who was three- dimensional—meaning literally three-dimensional, as in a person who wasn’t on a page or a computer screen. All this, after a youth full of romantic rejection! All this, after putting a lifetime bet on one woman! Who could have predicted this? Who could have predicted that there was such life in him yet?

Still, he told me, it was jarring. Rachel was gone now, and her goneness was so incongruous to what had been his plan. It wasn’t that he still wanted her—he absolutely did

not want her. He absolutely did

not wish she were still with him. It was that he had spent so long waiting out the fumes of the marriage and busying himself with the paperwork necessary to extricate himself from it—telling the kids, moving out, telling his colleagues—that he had not considered what life might be like on the other side of it. He understood divorce in a macro way, of course. But he had not yet adjusted to it in a micro way, in the other-side-of-the-bed-being-empty way, in the nobody-to-tell-you-were-running-late way, in the you-belong-to-no-one way. How long was it before he could look at the pictures of women on his phone—pictures the women had sent him

eagerly and

of their own volition—straight on, instead of out of the corner of his eye? Okay, sooner than he thought but not immediately. Certainly not immediately.

He hadn’t looked at another woman once during his marriage, so in love with Rachel was he—so in love was he with any kind of institution or system. He made solemn, dutiful work of trying to save the relationship even after it would have been clear to any reasonable person that their misery was not a phase. There was nobility in the work, he believed. There was nobility in the

suffering. And even after he realized that it was over, he still had to spend years, plural, trying to convince her that this wasn’t right, that they were too unhappy, that they were still young and could have good lives without each other—even then he didn’t let one millimeter of his eye wander. Mostly, he said, because he was too busy being sad. Mostly because he felt like garbage all the time, and a person shouldn’t feel like garbage all the time. More than that, a person shouldn’t be made horny when he felt like garbage. The intersection of horniness and low self-esteem seemed reserved squarely for porn consumption.

But now there was no one to be faithful to. Rachel wasn’t there.

She was not in his bed. She was not in the bathroom, applying liquid eyeliner to the area where her eyelid met her eyelashes with the precision of an arthroscopy robot. She was not at the gym, or coming back from the gym in a less black mood than usual, not by much but a little. She was not up in the middle of the night, complaining about the infinite abyss of her endless insomnia. She was not at Curriculum Night at the kids’ extremely private and yet somehow progressive school on the West Side, sitting in a small chair and listening to the new and greater demands that were being placed on their poor children compared to the prior year. (Though, then again she rarely was. Those nights, like the other nights, she was at work, or at dinner with a client, what she called “pulling her weight” when she was being kind, and what she called “being your cash cow” when she wasn’t.) So no, she was not there. She was in a completely other home, the one that used to be his, too. Every single morning this thought overwhelmed him momentarily; it panicked him, so that the rst thing he thought when he awoke was this:

Something is wrong. There is trouble. I am in trouble. It had been he who asked for the divorce, and still:

Something is wrong. There is trouble. I am in trouble. Each morning, he shook this off. He reminded himself that this was what was

healthy and

appropriate and the

natural order. She wasn’t

supposed to be next to him anymore. She was

supposed to be in her separate, nicer home.

But she wasn’t there, either, not on this particular morning. He learned this when he leaned over to his new IKEA nightstand and picked up his phone, whose beating presence he felt even in those few minutes before his eyes officially opened. He had maybe seven or eight texts there, most of them from women who had reached out during the night via his dating app, but his eyes went straight to Rachel’s text, somewhere in the middle. It seemed to give off a different light than the ones that contained body parts and lacy bands of panty; it somehow drew his eyes in a way the others didn’t. At five a.m. she’d written,

I’m headed to Kripalu for the weekend; the kids are at your place FYI. It took two readings to realize what that meant, and Toby, ignoring the erection he’d allowed to flourish knowing that his phone was rife with new masturbation material, jumped out of bed. He ran into the hallway, and he saw that their two children were in their bedrooms, asleep.

FYI the kids were there?

FYI? FYI was an afterthought; FYI was supplementary. It wasn’t essential. This information, that his children had been deposited into his home under the cover of darkness during an unscheduled time with the use of a key that had been supplied to Rachel in case of a true and dire emergency, seemed essential.