Excerpt

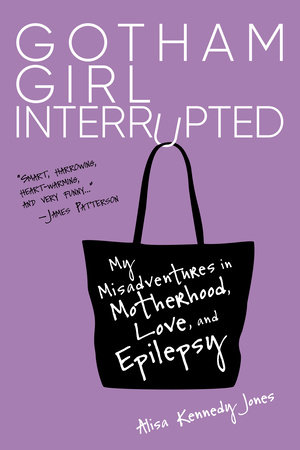

Gotham Girl Interrupted

Hello friend! Thank you for picking up this book or for borrowing it from some well-intentioned acquaintance. And thank you, well-intentioned acquaintance, for foisting it upon some unsuspecting reader!

In 2010, at the age of forty, I was diagnosed with a severe form of epilepsy. The cause was a mystery. What is epilepsy, you ask? Simply put, it’s an overabundance of electricity in the brain. Less simply put, it’s a serious chronic neurological disorder characterized by sudden, recurrent episodes of sensory disturbance, loss of consciousness, or convulsions, associated with atypical electrical activity levels in the brain. With more than forty different types of seizures, epilepsy affects sixty-five million people worldwide. Because of the complex nature of the brain, epilepsy can strike at any age and manifest differently depending on a variety of factors.

My seizures are the kind most often portrayed in the media, meaning the afflicted person falls to the ground and thrashes around until some brave-hearted Samaritan comes to the rescue. They’re dramatic. I look totally possessed when my eyes roll back into my head. If I’d been born during any other era, I’d likely be institutionalized or burnt at the stake by some angry white guys. Over the years, I’ve had hundreds of seizures. They tend to involve four phases: the first is the prodromal phase, which means before the fever. This is the emotional or intuitive voice that whispers, “Some shit’s about to go down.” The second phase is the aura. Sometimes an aura can be as subtle as a shimmer of light at the edge of my field of vision. Other times, it’s more hallucinogenic and has me asking, “Whoa, what kind of Donnie Darko movie is this?” Then, there’s the third ictal phase—that’s the seizure itself, the electrical storm in my brain where I’m usually on the ground in convulsions. To those around me, it may look agonizing but I’m actually not feeling any pain at this point—just a gorgeous black bliss. Lastly, comes the post-ictal phase where the convulsions have stopped and I’m out cold. In the moments when I’m regaining consciousness, I might be confused or frightened, but mostly I can really only focus on what’s directly in front of me—often it’s the smallest things.

Seizures tend to put one in a constant state of disaster preparedness. Picture a pilot fixing an airplane engine while it’s flying or, in my case, as it’s crashing. Some of the preparations I’ve made over the years might seem ridiculous, but then I’ve never claimed to be the most logical girl. Still, epilepsy is about having a plan, a “Here’s what we’re going to do . . .” and then improvising as things with the condition evolve.

People tend to think of epilepsy as something that primarily impacts children, but it can strike at any time, no matter how healthy you are. As with so many stigmatized chronic conditions, I tried to keep mine under the radar for years for fear that people might misjudge, mock, or withdraw. If I wasn’t having seizures all the time, I reasoned, not everyone had to know.

Then, in 2015, I had “the big one” that nearly destroyed me, laid me flat and left me the most vulnerable I’ve ever been. It was brutal. It changed almost every aspect of my life, forcing me to start completely over from zero—I couldn’t speak, eat, or work. I couldn’t go out in public without frightening people. The experience led me to believe that people do need to know more about this condition and that perhaps they also needed a different narrative approach. I know I certainly did.

For years, I’ve called myself a spaz. Why? Because when you are a nerdy, too-tall, introverted, single girl-mom with chunky glasses, who has epilepsy, anxiety, and depression, at a certain point you want to take the derogative term back from the historically mean asshats of the world—primarily people who say epileptics are spastic freaks who are addicts, junkies, drunks, crazy, dangerous, deranged, possessed, demonic, divine, incontinent, unreliable, unable to hold down a job, unable to care for children, and so on.

Whether you have epilepsy or not, chances are you know someone who is affected by it. I happen to think we are all a little neurodiverse—meaning we are all uniquely neurologically wired. Where one person is the quintessential extroverted life-of-the-party, another is an introvert completely overwhelmed by people, chatter, and music. Everyone experiences the world according to her/his/their neurological makeup, and we shouldn’t have to go around faking “normal” all the time.

Epilepsy is certainly not all that defines me, but it’s also a thing that’s not going away anytime soon. To go around hiding the fact is not only exhausting; it’s totally missing out on the richness and hilarity that comes when we are all put together, as people, side by side and forced to understand and deal with difference. And I’m with Carrie Fisher on this one; I am constantly perplexed by the stigma attached to mental illness, the various chronic neurological conditions and the differently-abled.

If you are walking (or rolling) around New York City or any town with epilepsy, living your life, connecting with people and able to feel compassion for friends, family, and your fellow humans, or to feel even slightly productive in your own right, you deserve a standing ovation—not a kick in the teeth.

We need to stop being such uptight weenies and admit that it’s high time the world learns to adapt, make room for, and embrace all kinds of people along the spectrum of ability and neurodiversity instead of everyone always tiptoeing around topics of neurology, mental illness, autism, epilepsy, and so many other chronic conditions governed by our brains and genetics.

Over the years, people’s questions about my conditions have ranged from “Do seizures hurt?” to “How come you’re not completely developmentally delayed and/or traumatized?” More often than not, the questions are more a reflection of the person asking them than anything to do with me. My answers are typically, “No, my seizures don’t hurt” and, “Actually, they can be quite beautiful.” Indeed, some of the instances when I’ve felt most intellectually inspired, most human, and often most creative in my life happen when I fall, thrash around, and then get back up. For me, it’s like the ultimate system reboot—a vibrant Technicolor awakening each time. I won’t pretend that it isn’t a doozy or not complicated, but my family (and Oprah) raised me to believe that my ideas, thoughts, and opinions mattered, that they were grounds for more inquiry, and that it’s only when we are able to connect the dots between our deepest points of vulnerability and tell our stories that we can change things.

So, this is my story about not tiptoeing around the difficult dots. Little did I know (as I was writing this) how much the concept of neurodiversity would come to matter, the idea that whether you have anxiety, depression, addiction, bipolar disorder, autism, or epilepsy, the point is your own individual neural wiring might in fact be your magic rather than a tragedy, that it might allow for finding meaning in places you never expect it to and with people you’d never anticipate having in your life. Yes, you may be different; you may be in a chronic waltz to feel at home in your head or in your body. You may even feel trapped in there for a long stretch (as I was), but it doesn’t make you less; it makes you magic.

That’s what this book is about.

The one superpower epilepsy (or any chronic condition for that matter) shouldn’t give you, however, is invisibility, so I wanted to write stories about loveable weirdos with all different types of wiring to ask, Why can’t the awkward, spazzy nerd win after all? Why can’t she/he/they end up with the good, funny, amazing person who is her/his/their own equal and opposite counterpart? What’s to say they can’t live out a truly great rom-com? Why can’t they have a full tribe of kooky friends and family who have their back? Why can’t they have a rich, rewarding career? Why, with technology, science, and modern medicine should there be any hindrance?

For my part, I have told these stories as I remember them, which means salted and peppered with truth and exaggeration, with names changed to protect the guilty and the innocent, starting with my parents. At times, it’s more of a rescue-and-recovery operation than a memoir because I’m filling in certain blanks with reflections, bad ideas, and inappropriate metaphors. I wrote them in a kind of fever dream, my own series of seizures, a lightning-bolt flipbook of time-lapse photography on a hyperloop. Factor in a few grim flashbacks, select absurd hypotheses, and misunderstandings made funnier with prescription drugs, and there might be a book in it.

Epilepsy can lure you into powering down your whole self— especially your funny side—and I believe this is a mistake. Some things are out of my control. Others, well . . . let’s just say are a self-made mess. Some are absurd. The breezy humor you find in this book may be a defense mechanism, but I believe it’s a necessary one at times and an excellent self-care tool when you can tap into it. By taking a comedic approach to these stories, please know that there’s never any intention to trivialize or diminish the suffering people experience as a result of epilepsy. It’s a devastating condition, but we don’t have to stay devastated.

Okay, time to get to your safe space, people. This is how it always begins. Here comes the shimmer . . .