Excerpt

Death in Focus

Chapter 1

1933

Elena narrowed her eyes against the dazzling sunlight reflected off the sea. It was warm in the late May morning, the light so much softer here in Amalfi than it would have been at home, on the English coast. Brilliant sprays of bougainvillea arched against the sky, burning purples and magentas, vibrant with color but without perfume. They covered parts of the ancient walls; old, mellow stone houses; and flights of stairs down toward the whispering sea. There were glimpses of mosaic pavement, two thousand years old, and children playing marbles. Above them seagulls hovered on the wind, looking for scraps.

Elena was staring at a woman farther down the steep hill. She wore a scarlet dress and was dancing by herself, within her own imagination, perhaps lost in time in this exquisite town on the edge of the Mediterranean, which had lured the Caesars from the wealth and intrigue of Rome to dally here.

“Do you suppose she is real?” a man’s voice asked gently behind Elena, on the edge between pleasure and laughter. “Or could she be a figment of a fevered imagination?”

She turned to look at him. He was noticeably taller than she, and the sun caught the auburn lights in his thick hair. His face was in shadow, but she could see the outline of it, his strong bones.

“Oh, she’s real,” she replied with a wide smile. “Should I be sorry? Would a vision be better?”

“Only for a little while. Reality always comes back. If it didn’t, you’d be considered mad.”

“Oh dear,” she said, keeping a straight face with some difficulty. “And I thought dancing in a red dress was the ultimate sanity.”

He shrugged. “An old woman with a bag of onions would be more interesting than most of the delegates at the economics conference I’m attending!”

Elena laughed outright. “I will tell Margot you said that!”

“Margot? Is that her name?”

“A woman, dancing alone in a red dress? That could only be my sister Margot!” She meant both the implied praise and the exasperation, and yet fleetingly she wished that the figure could have been her.

The man looked startled, as if unsure for a moment whether to believe her or not.

She saw it and laughed again. “Really.”

Margot was her older sister, who had come to this very tedious conference on a whim. She was bored, and she had wanted to go to Amalfi anyway, so she had offered to accompany Elena, who was to photograph the delegates. “It will be more fun to go together,” Margot had insisted. “You can’t take photographs all the time,” she had added in the slightly disparaging way she always used when speaking of Elena’s photography.

For Margot, Elena’s photography was something to do and a way to make a moderate living, but she also knew it was a passion that she herself did not understand.

Elena could not argue. Margot could usually read her too well, at least when it came to uncomfortable things like self-protecting lies. Perhaps because she was four years older.

And of course Margot knew about Aiden Strother. Not all of it. Nobody but Elena knew that, although no doubt others had guessed. Elena had started out after university in a high position in the Foreign Office, due not only to her excellent academic record, but in large part to her father’s position over the years as British ambassador in several of the most important cities in Europe: Berlin, Paris, and Madrid in particular.

Elena had fallen in love with Aiden while working for him. It had been easy to do. He was charming, handsome in a wry, good-humored way, and clever. Very clever. He fooled them all utterly, even Elena. She was too in love to accept the signs, which in hindsight she now saw quite clearly. He had betrayed them all, and she had been stupid enough to help him, albeit unwittingly. Looking back, she burned with shame at her own stupidity. The only good thing was that nobody thought her guilty of complicity, only of being young and incredibly naïve.

All the same, she had been asked to leave, to the acute shame and embarrassment of her father, Charles. He had felt that, of his two daughters, she was the one to follow in his footsteps, perhaps rise as high as a woman could in the Foreign Office. Elena’s brief enchantment with Aiden was still an obstacle between her and her father. She was guilty of gross stupidity and had not denied it. It still hurt when anyone chose to mention it, not out of longing for a love lost—or even an illusion of it—but because she had been stupid and had let everyone down, especially herself.

Charles had never quite understood his elder daughter, Margot, though he had always adored and admired her. Everyone felt the consuming grief that had smothered her life when her husband of one week had been killed in the last month of the war.

Now, alone in the square below, Margot had stopped dancing and was beginning to walk slowly up the steps toward Elena and the young man, every now and again lost to sight by a bend in the walls or an overexuberant bower of colored bracts.

“Don’t tell me she’s an economist?” The young man spoke again, amusement still in his voice, but quieter, as if he were aware of her momentary emotional absence. Fifteen years after the war, everyone still had their griefs: loss of someone, something, a hope or an innocence, if not more. And fear of the future. It was in the air, in the music, the humor, even the exquisite, now fading light.

“Certainly not.” Elena kept the lift in her voice with an effort. “And please don’t ask me if I am.”

“I wouldn’t dream of it.” He held out his hand. “Ian Newton. Economic journalist. Sometimes.”

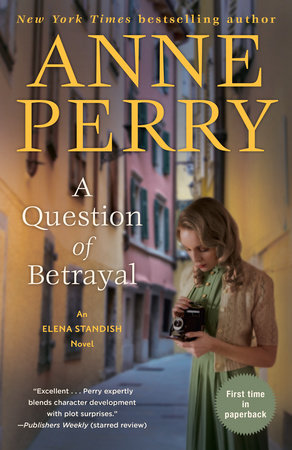

She took it. It was strong and warm, holding hers firmly. “Elena Standish. Photographer. Sometimes.”

“How do you do?” he replied, and then let go of her hand.

“And that is my sister, Margot Driscoll,” Elena said.

“Not Standish . . . she’s here with her husband?”

“Margot is a widow. Her husband, Paul, was killed in the war.”

Ian Newton nodded. Of course . . . This was a situation encountered every day, even now. He looked over to Margot, destined to dance alone in a world populated by superfluous women.

“Will you and Mrs. Driscoll dine with me tonight?”

“I’d like that,” Elena answered for both of them. “Thank you. We’re staying at the Santa Catalina.”

“I know.”

“Do you?”

“Certainly. I followed you here.”

She did not know whether to believe him, but it was, surprisingly, a nice idea. “Eight o’clock? In the dining room?” she suggested.

“I’ll be waiting for you by the door,” he replied, then turned and walked away up the hill easily, straight-backed.

The next moment, Margot appeared on the steps from the square. She was as unlike Elena as sisters could be. Margot had dark eyes and hair like black silk. She was lean and elegant, no matter what she wore. Elena was the same height; she had a certain grace, but she could not match Margot’s. Her eyes were quite ordinary blue, and her hair was nearly blond. She felt insipid beside Margot’s drama.

“Daydreaming again?” Margot asked, exasperation thinly veiled in her voice. She hardly ever forgot her four years’ seniority. “If you want to be a serious photographer, you’ll have to take some decent pictures, which you won’t do standing here.”

“I don’t know,” Elena said patiently. She had been nagged many times before, and although she knew it was true, she also knew Margot said it out of frustration and affection. “I got a couple of a woman dancing alone in the square below, in a scarlet dress. A little crazy, but a nice study.”

Temper flashed in Margot’s eyes for an instant, and then vanished again. “I’ll have them, please.”

“Don’t be daft!” Elena said impatiently. “I’m not wasting film on you. I just like watching you enjoy yourself.” It was the truth.

Margot put her arm round Elena and silently they walked up the hill, toward the hotel.