Excerpt

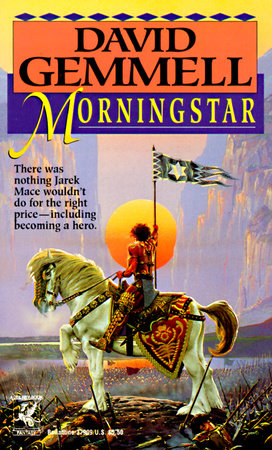

Morningstar

1

IT IS ALL ruins now but back then, under a younger sun, the city walls were strong and high. There were three sets of walls on different levels, for Ziraccu was an ancient settlement, the first of its buildings raised during the Age of Stone, when neolithic tribesmen built their temples and forts on the highest hills of this Highland valley. Hundreds of years later—perhaps thousands, for I am no expert on matters historical—a new tribe invaded the north, bearing sharp weapons of bronze. They also built in the valley, throwing up walls around the four hills of Ziraccu. Then came the Age of Iron and the migration of the tribes that now populate the mountains of the north. The painted warriors of bronze were either killed or absorbed by these fierce new invaders. And they, too, built their homes in the high valley. And Ziraccu grew. On the highest levels dwelled the rich in marble palaces surrounded by fine gardens and parks. On the next level down dwelled the merchants and the skilled craftsmen, their houses more homely yet comfortable, built of stone and timber. While at the foot of the hills, within the circle of the lower walls, were the slums and tenements of the poor. Narrow streets, stinking with sewage and waste, high houses, old and dilapidated, alleys and tunnels, steps and stairways, dark with danger and bright with the gleam of the robber’s blade. Here there were taverns and inns where men sat silently listening for the watchmen.

Ziraccu, the merchant city. Everything had a price in Ziraccu. Especially in the years of the Angostin War, when the disruption to trade brought economic ruin to many.

I was young then, and I could weave my stories well. It was a good living, traveling from city to city, entertaining at taverns—and occasionally palaces—singing and magicking. The Dragon’s Egg was always a favorite, and I am sorry it has fallen into disregard in these latter days.

It was an evening in autumn in Ziraccu, and I was hired to play the hand harp at a wedding celebration in the south quarter. The daughter of a silk merchant was marrying the son of a spice trader. It was more an alliance than a marriage, and the bride was far from attractive. I will not dwell on her shortcomings, for I was, and am, a gentleman. Suffice to say that her ugliness was not so great as to be memorable. On the other hand, I felt great pity for the groom, a fine upstanding youngster with clear blue eyes and a good chin. I could not help but notice that he rarely looked at his bride, his eyes lingering on a young maiden seated at the foot of the table.

It was not the look of a lascivious man, and I knew instantly that these two were lovers. I felt for them but said nothing. I was being paid six silver pennies for my performance, and that, at the time, was more important than true love thwarted.

The evening was dull, and the guests, filled with good wine, became maudlin. I collected my fee, which I hid carefully in a special pocket in my right boot before setting off for my lodgings in the northern quarter.

Not a native of Ziraccu, I soon became lost, for there were no signs to be seen, no aid to the wanderer. I entered an ill-smelling maze of alleys, my heart pounding. My harp was slung over my right shoulder, and any who saw me would recognize the clothes of a bard—bright yellow shirt and red leggings. It would be most unusual to be accosted, for bards were rarely rich and were the only gatherers of news and gossip. We were welcome everywhere—especially those of us who knew a little magick. But—and this is the thought that occupied me—there were always those who knew nothing of tradition, some mindless robber who would plunge his knife into my belly before he realized his mistake.

Therefore, I walked with care through the dark alleyways, drawing myself up to my full height, pulling back my shoulders so as to appear tough, strong, and confident. I was not armed, not even with a short knife. Who would need a knife at a wedding?

Several rats scurried across my path, and I saw a corpse lying by the entrance to a short tunnel. In the bright moonlight it was easy to see that the corpse had been there for some days. His boots were gone, as was his belt.

I turned away my gaze and strode on. I never did like to look upon corpses. No man needs such a violent, visual reminder of his mortality. And there is no dignity in death. The bladder loosens, the bowels empty, and the corpse always assumes an expression of profound idiocy.

I walked on, listening for anything that might indicate a stealthy assassin creeping toward me. A foolish thing to do, for immediately the thought comes to you, the ear translates every sound into a footfall or the whisper of cloth against a wall.

I was breathing heavily when at last I came out onto a main thoroughfare I recognized.

Then the scream sounded.

I am not by nature heroic, but upbringing counts for much in a man’s life, and my parents had always made it clear that a strong man must defend the weak. The cry came from a woman. It was born not of pain but of fear, and that is a terrible sound. I swung around and ran in the direction of the cry; it was a move of stunning stupidity.

Turning a sharp corner into a narrow alley, I saw four men surrounding a young woman. They had already ripped her dress from her, and one of the attackers had loosened his leggings, exposing his fish-white legs and buttocks.

“Stop that!” I shouted. Not the most powerful opening line, I’ll admit, especially when delivered in a high-pitched shriek. But my arrival stunned them momentarily, and the naked man struggled to pull up his leggings, while the other three swung to face me. They were a grotesque bunch, ugly and filthy, dressed in greasy rags. Fight them? I would have given all I had not to touch them.

One of them drew a dagger and advanced toward me, grunting out some kind of inquiry. The language he used was as foul as his look. The strangest thoughts come to a man in danger, or so I have found. Here was a man with no regard for his appearance. His face and clothes were filthy, his teeth blackened and rotting, yet his dagger was sharp and bright and clean. What is it that makes a man take more care of a piece of iron than this own body?

“I am a bard,” I said.

He nodded sagely and then bade me go away, using language I would not dream of repeating.

“Step away from the lady, if you please,” I told them. “Otherwise I shall call the watch.”

There was some laughter at this, and two of the other three advanced upon me. One sported a hook such as is used to hang meat, while the second held two lengths of wood with a wire stretched between them. The last of them remained with the girl, holding her by the throat and hair.

I had no choice but to run, and I would have done so. But fear had frozen my limbs, and I stood like a sacrificial goat waiting for the knife and the hook and the wicked throat wire.

Suddenly a man leapt from the balcony above to land in their midst, sending two of them sprawling. The one on his feet, he of the meat hook, swung his weapon at the newcomer, who swayed aside and lashed out with a sword belt he was holding in his left hand. The buckle caught the man high on the left cheek, spinning him from his feet. It was then that I saw that the newcomer was wearing only one boot and was carrying his sword belt in his hand. Hurling aside his scabbard, he drew his blade, lancing it through the neck of his nearest foe. But the first of the villains I had seen rose up behind the newcomer.

“Look out!” I cried. Our unknown helper spun on his heel, his sword plunging into the chest of his opponent. I was behind the man, and I saw the blade emerge from his back; he gave a strangled scream, and his knees buckled. The warrior desperately tried to tear his sword loose from the man’s chest, but it was stuck fast. The rogue with the throat wire leapt upon the newcomer’s back, but before he could twist the wire around his intended victim’s throat, the newcomer ducked and twisted, hurling his attacker into a wall. As the villain rose groggily, the newcomer took two running steps, then launched himself through the air feet first, his one boot cracking against the base of the man’s neck and propelling his face into the wall. There was a sickening thud, followed instantly by the crunching of bones. The sound was nauseating, and my stomach turned.

The last of the villains loosened his hold on the girl, throwing her to the ground and sprinting away into the shadows. As the girl fell, she struck her head on the cobbles. I ran to her, lifting her gently. She moaned.

“You bastard! I’ll see you dead! You’ll not escape me!” shouted a voice from an upper window. I glanced up to see a bearded man upon the balcony. He was hurling abuse at the newcomer.

It did not seem to perturb the fellow. Swiftly he wrested his sword clear of the corpse, then gathered his second boot, which was lying some distance away against a wall.

“Help me with her,” I ordered him.

“Why?” he asked, pulling on his boot.

“We must get her to safety.”

“There he is! Take him!” screamed the man on the balcony. The sound of running footsteps came from the alley.

“Time to go,” said the newcomer with a bright smile. At once he was on his feet and running.

Armed men rushed into sight and set off after him. The officer of the watch approached me. “What is happening here?” he asked.

I explained briefly about the attack on the girl and of our sudden rescue. He knelt by the still-unconscious woman, his fingers reaching out to feel the pulse at her throat. “She’ll come around,” he said. “Her name is Petra. She is the daughter of the tavern keeper Bellin.”

“Which tavern?”

“The Six Owls; it is quite close by. Come, I’ll help you carry her there.”

“Who is the man you are chasing?”

“Jarek Mace.”

He said the name as if it were one I should know, but when I professed ignorance, he smiled. “He is a reaver, a thief, an adulterer, a robber—whatever takes his fancy. There is no crime he would not commit if the price were worth the risks.”

“But he came to our aid.”

“I doubt that. We had him cornered, and he ran. I would guess he jumped from the window to escape us and landed in the midst of a fight. Lucky for you, eh?”

“Extraordinarily lucky. Perhaps it was fate.”

“If fate is kind to you, bard, you will not meet him again.”

That was the first time I saw the Morningstar.