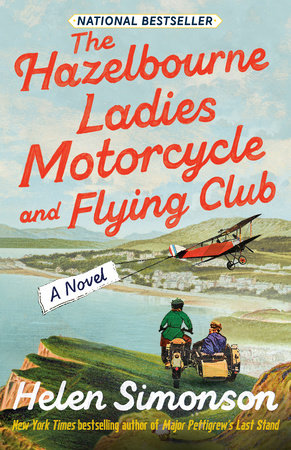

Excerpt

The Hazelbourne Ladies Motorcycle and Flying Club

Chapter 1In the first place, it did not seem quite right that a girl that young should be free to wander the hotel and seaside town without a chaperone. She looked respectable enough, though she was pale as alabaster and thin as a wet string. She was clothed in a brown wool dress, perhaps a bit too big, that fell decently to the ankles, and her leather boots still had a shine of newness on them. She was some sort of connection and companion to Mrs. Fog, an old lady from a grand family in the shires, but it seemed to Klaus Zeiger that the old lady encouraged far too much independence. Since her arrival at the Meredith Hotel, the girl was always to be found tripping through the grand public rooms alone, or curled up in an armchair deep in a book, oblivious to all. And now, with the old lady having ordered dinner in her room again, the girl wished to be seated in the Grand Dining Room alone.

“I hoped, because it was early . . .” she said, peering past Klaus into the high-ceilinged room, which functioned as both restaurant and ballroom. She spoke respectfully but there was a firmness to her tone and a faint lift of the chin. “A quiet corner somewhere?” Only two tables were occupied; each with a pair of elderly ladies nodding their hats at each other. The room echoed a little. Silverware pinging against glass, shoes loud against the parquet floor. The tall potted palms stirred in an unknown draft and from beyond the tall French windows came the murmur of voices from the seafront and the low booming of the sea against the pebbled shore. Later would come the dancing crowds, the loud hotel orchestra, and the crude drunken Saturday night carousing—all things that would never have been countenanced before the war.

“I’m very sorry, miss,” Klaus repeated, drawing himself up. He was the lone waiter at this hour, and in the absence of the headwaiter, who was having his own dinner in the kitchen, he felt keenly the need to defend the ragged standards that were left. “Can I arrange to have something sent to your room?”

“Please don’t be sorry,” the girl said. “We are all bound by our duties, are we not?” She gave him a brief smile and walked away down the long marble floor of the glass-enclosed Palm Terrace. Her smile made him ashamed. Not answering him about the dinner tray made him irritated. Turning away a hotel customer added a new string to the vibration of anxiety that hummed in his veins.

He tugged down surreptitiously at the sleeves of his black jacket, now a little stiff from age and mothballs, and rubbed the arthritis in his knuckles, wondering if he should have relented. Would this quiet young woman eating tonight’s chicken quenelles behind a potted palm have been more scandalous than the women who would come later in the evening to dine intimately or in great parties, with men, laughing openmouthed over champagne and bending the fringed edges of their décolletages into the mock turtle soup?

He cast a discreet eye over his tables, looking for the dropping of hands, the setting down of cutlery that would signal he was needed, and sighed. Everything was confusing now. He had recognized one of the pair of diners from before the war, the widow of a wealthy brick manufacturer and her spinster sister, who lived in a large villa on a hill above the town. Kind women who appreciated fine service, who blushed at a carefully dispensed compliment, who always left a little gratuity hidden under the napkin. He had made a mistake today, exclaiming at seeing them after so long, trying to kiss their gloved hands. They had responded with squeezed lips, their eyes darting and anxious. Like a blow to the ribs, he understood why the hotel manager had been hesitant and cruel in hiring him back. Two months’ trial only and an instruction to keep his mouth shut as much as possible. Klaus had been hurt, almost to the point of refusing.

Before the war, a German waiter commanded the greatest respect. But what was the point of standing on his pride? After six humiliating months in the internment camp, and banned from returning to the coast, he had nearly starved in London, scratching for whatever job they would give to a German. He remembered the long steaming hours at the sink, washing dishes in a men’s hostel; waiting tables at an asylum where an inmate might thank you for the supper or throw it in your face; a pallet on the cellar floor in exchange for working in a boardinghouse dining room. To return home to Hazelbourne-on-Sea he needed this job and the room that came with it. He wondered, as a tremor ran down his spine, where he would go now if the two women, or the young girl, made a complaint.

In the lobby of the Meredith Hotel, Constance Haverhill paused, pretending to admire the flowers in the towering urn on a marble table at the foot of the grand staircase. The reception desk seemed busy with a large party arriving and two or three gentlemen chatting to the concierge. Her rejection from the dining room fresh, she felt too humiliated to push herself forward to the center where the clerk would offer her the menu of the day and she would be forced to publicly decide between broth or fish paste on toast and then accept the plain dinner and one of the three rotating puddings, most of them custard. On their first night, she and Mrs. Fog had dined together, but dinner had been taken in her room these last three days and Constance was tired of the lingering smell of gravy and the awkward waiting for the used tray to be removed.

There would be plenty of time in the years to come to feel the limits of a life as a spinster. Lady Mercer, who fancied herself Constance’s patron and had sent her to the seaside to look after Mrs. Fog, her mother, had been loud in her opinion that now, with the war over and women no longer needed in men’s professions, Constance would be well advised to take up as a governess. Joining the family once a week for dinner with the children, trays in one’s room when important guests came to dine, sharing one’s room on occasion if there were too many ladies’ maids at a weekend party. Constance shivered at the thought. As a young girl, she had seen the governesses come and go, for Lady Mercer couldn’t seem to keep one. And when one left, Constance’s mother would be called in to help during the transition. On those occasions, Constance would go with her mother to the big house and join in the lessons with Rachel, their daughter.

Her mother and Lady Mercer had been schoolgirls together, and though the former married a farmer and the latter a lord, they maintained the fiction of a lifelong affection of friends and equals by never allowing the crudeness of money to come between them. Constance’s mother had never received a wage for the many services she had provided under the guise of friendship and the patronage of the Clivehill estate. Instead there was always a small velvet bag of sovereigns at Christmas, the discarded dresses of prior seasons, a supply of preserved fruit that she and Constance helped the kitchen put up every summer. There were invitations to hunt balls and to fill out the numbers at some of the less distinguished dinners held in Clivehill’s magnificent dining room. Constance herself had plenty of training in working for, and being grateful to, the Mercer family, including having run their estate office for most of the war. But with the Armistice, it had been made clear she was surplus to requirements and her need for paid employment was now pressing. As a thank-you, she had been promised these few short weeks at the seaside, during which she might float in the luxurious anonymity of hotel life. But her rejection from the dining room made her uncertain future seem all the more immediate.

Her reverie was interrupted by the slightest ripple of tension in the lobby. There were no raised voices but only the urgent cadence of a disagreement being conducted discreetly by the open French windows. The hotel’s undermanager, a shy youth of some relation to the hotel manager, was bent to converse with a woman about Constance’s age who was sitting half-concealed on a settee, reading a newspaper. There seemed to be some issue regarding the woman’s ordering tea and Constance drifted closer with all the natural curiosity of someone fresh from her own humiliation.

“Oh, don’t turn me out, Dudley. I’m having dinner here with my mother later,” said the young woman. “Just bring me a tea table and I’ll promise to hide behind the tablecloth.”

“But we cannot serve you, Miss Wirrall . . .” said the undermanager, his face reddening at her familiarity. He seemed like a man on the third or fourth round of saying exactly the same thing. Constance could see that the young woman, though discreetly tucking her ankles under the seat and partly covered by the day’s headlines, was wearing slim brown wool trousers tucked into the tops of thick black knee boots. A green tweed jacket and white silk scarf completed the ensemble. A leather helmet and goggles lay abandoned on a low table. The woman’s chestnut hair was fuzzy and loose in its pins, no doubt from wearing the helmet, and gave her a slightly disreputable look.

“Take pity on me,” said the girl, but the undermanager shook his head. She seemed to catch sight of Constance in that instant and grinned before tossing the newest of her long list of arguments. “I’m liable to die of thirst, Dudley.”