Excerpt

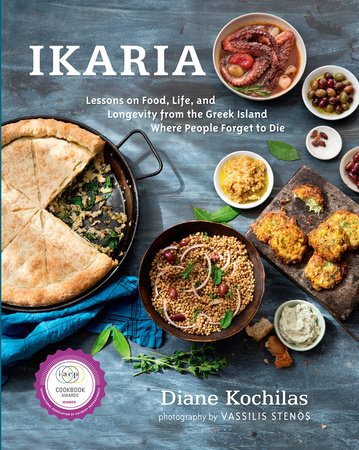

Ikaria

Introduction

Ikaria Feeds the Soul

I first touched foot on the island in 1972 as a 12-year-old New York City kid inured tosticky urban summers, insipid American food, and strict curfews. My Greek was nonexistent, but somehow it didn’t matter. I felt at home, as though Ikaria was in my bones. It was, I guess. I grew up with it all around, the child of Ikarian immigrants. My father left his village, Raches, in 1937 and never was able to make it back, settling instead, right after the war, in New York City. Despite our physical distance from it, Ikaria was woven into the texture of our lives. We lived in an Ikarian enclave in Jackson Heights, Queens, and all my parents’ friends were from the island; by default and design, we kids were also friends. Now, so are our own children. Bonds among islanders from Ikaria cross oceans and generations. We never thought these ties and our roots to the island to be anything but the norm, even in a society as mobile as America.

Historically, Ikaria has always been isolated and poor, a speck of rock 99 miles long in the middle and roughest part of the Aegean, where political undesirables were exiled from the Byzantine era to the 1960s. But in remoteness and want, islanders learned to be self-reliant, independent of thought, and close-knit, to disdain the pursuit of material acquisition and live simply and essentially, to pay little heed to the zeitgeist of the times, indeed, to pay no heed to time at all. Ikaria is known as the island where people do not live by the clock, where punctuality is not necessarily a virtue, where the time of day is always “late thirty,” a kind of running joke. Yet, they outlive most clocks, for the island is home to some of the longest-living people on earth, a demographic and statistical anomaly that has catapulted Ikaria and its people to unexpected fame in the last few years.

Ikaria is one of the Blue Zones,® a term coined by the Belgian demographer Dr. Michel Poulain, who together with Dr. Gianni Pes of the University of Sassari in Italy and Dan Buettner, author of the book

The Blue Zones, have been studying the planet’s pockets of longevity since 2003, under the aegis of the National Geographic Foundation and, in the case of Ikaria, the AARP as well as a series of other corporate funders. Poulain, blue pen in hand, literally drew circles (in blue) on the map one day around places such as Ikaria, Okinawa, Sardinia, Costa Rica, and a community of Seventh Day Adventists in Loma Linda, California, where people seem to live an inordinately long time. His blue-circled zones gave birth to the term that has become synonymous with longevity, but the trademark is owned by Buettner.

What sets Ikarians apart, even from other nonagenarians around the world, is that they live well—with little cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia, or other age-related ailments—drinking wine, enjoying sex, walking, gardening, and socializing, in other words, being very much alive, in their veritable, modern-day Shangri-La. Since 2008, a battery of scientists, journalists, demographers, and others has been trying to figure out the secrets to this seeming paradise. Food, lifestyle, and such a deep-rooted disregard for living by the clock that there is really no stress have all, somehow, played a role in giving Ikarians good, long lives.

In this book, a tribute to the place and to our countless friends there, both of which have given me and my family more than words can ever express, I set out not to codify Ikaria’s diet or lifeways in hopes of uncovering some key, but, rather, to honor them and shine a loving, and, I hope, knowing, light on this once-forgotten piece of rock, that looks like a wing and is named for the Icarus of Greek myth. I hope that anyone who picks up this book might glean a few lessons for how to live more essentially and less anxiously, by cooking and eating simple, real food that is largely plant-based, by ignoring the clock’s reign, if even for a bit, and by forging relationships that defy generations and are both meaningful and long-lasting. Those are the things Ikaria has given me and that I hope to share with others.

Grape Leaves Stuffed with Rice and HerbsDolmadakia

This is a traditional recipe for stuffed grape leaves, with one local touch in the use of fennel fronds,preferably from wild fennel.If you have access to fresh grape leaves in the spring, by all means collect and use them. You canblanch and freeze the fresh leaves. Trim off the tough stems, blanch in batches, cool in an ice bath,and pack them in stacks of 50 in plastic zip-seal bags, pressing out all the air, then freeze.As a general rule, dolmadakia may be stuffed either with rice and herbs, as in this recipe, in aversion often referred to as yialantzi, or with a combination of rice and ground beef or lamb. Thesweetness of so many onions in the filling counters the innate acidity of the leaves.

Makes 6 to 8 servings

1/2 pound (220 g) fresh grape leaves, or 1 jar (16 ounces [450 g]) brine-packed grape leaves

1/2 cup Greek extra virgin olive oil

5 large onions, finely chopped

1 cup finely chopped scallions

2 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 cup long-grain rice

1 scant teaspoon ground cumin

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

4 to 5 cups water

1 cup finely chopped fennel fronds

1/2 cup finely chopped fresh dill

1/2 cup finely chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

1/3 cup finely chopped fresh mint

Juice of 2 lemons, strained

Plain Greek yogurt (optional)

1. If using brined grape leaves, rinse them very well and blanch them in scalding water for 2 to 3 minutes to soften. Remove with a slotted spoon, and place in a bowl of ice water. Drain and rinse several times.

2. If using fresh grape leaves, trim the stem and use directly.

3. In a large, heavy skillet, heat 1/4 cup of the olive oil over medium heat. Add the onions and scallions and cook until completely soft, 8 to 10 minutes. Add the garlic and stir for 1 minute. Add the rice and cook, stirring constantly, for 5 minutes. Add the cumin, salt and pepper to taste, and 1 cup water. Cover and simmer until the rice is softened but not cooked completely and the water absorbed, about 10 minutes. Remove and cool. Toss in the herbs.

4. Separate the grape leaves that are too small or too irregular to roll. Pour 2 tablespoons olive oil in the bottom of a medium saucepan and spread 4 or 5 of the irregular leaves over the oil.

5. To assemble the stuffed grape leaves, take one leaf at a time, and snip off any remainder of a hard stem. Place 1 teaspoon of the rice mixture in the center bottom of the leaf. Fold the left and right sides over the filling and roll up, gently but tightly, from bottom to top, until a bite-size log is formed. Place seam-side down in the pot. Repeat with remaining stuffing and leaves. Pour the remaining olive oil, lemon juice, and enough water to cover the leaves by about 3/4 inch (2 cm) into the pot. Place a piece of parchment paper then a plate over the grape leaves so they don’t loosen while cooking. Cover the pot and cook over low heat until the leaves are tender and the rice is thoroughly cooked, 40 minutes.

6. Serve warm or cold, with yogurt on the side, if desired.