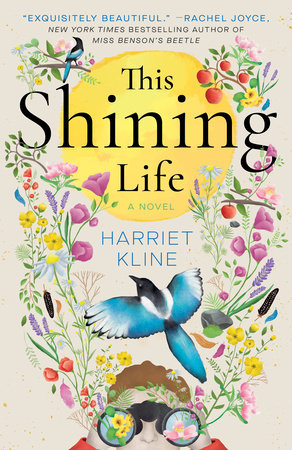

Excerpt

This Shining Life

OllieMy dad died. He gave everyone a present before he died. He gave me a pair of binoculars. They smell of books that haven’t been read for a very long time. When I put them against my face they feel heavy. I can feel them pressing on my bones. My dad hasn’t got any bones. We burned them all and threw the ashes around by the river. When we’d finished we saw a heron flying out of the woods. Auntie Nessa sighed and said: “There he goes.”

She said the heron was my dad, but it wasn’t. I looked at it through the binoculars and saw its beak and some feathers sticking up on its head. My dad didn’t have a beak, or feathers. He had yellow curly hair and big lines in the skin around his eyes that Angran calls crow’s feet. Everyone stood there watching the heron and Mum did that thing of crying and smiling at the same time, while she held on to Auntie Nessa’s hand. I didn’t really think it would be him. I knew it must be a turn of phrase, but I didn’t know what it meant. When Mum says my bedroom is a bomb site I know she means it’s messy, but I’ve never heard a saying about dead people and herons and that made me nervous. I was scared to say anything about it in case I got something wrong. I hate getting things wrong.

Mum had come to sit on my bed at the beginning of the school holidays and she said: “Dad’s dying.”

I thought she meant he was dying for a cup of tea or a bit of peace and quiet. It didn’t seem likely that he was actually dying. I could hear him washing up in the kitchen, opening the cutlery drawer and not shutting it again. He wasn’t in a bed with blood coming out of him, he was singing to the Beach Boys. So I said: “Dying for what?”

She said: “The brain tumor they found last week, love. They can’t take it away.”

So that time it wasn’t a turn of phrase. I’d got it wrong. Mum had got it wrong too because I didn’t ask what he was dying of, and she answered as if I had. People get it wrong all the time. But I don’t like it. Especially not when people are crying and holding each other’s hands. Then I know that getting it wrong makes things worse.

Prognosis DayRuthNessa drove them to the hospital, hurtling them there, it seemed, with the shadows of the trees on the valley road flickering through the car. They lived eight miles out of town at the end of a narrow lane, and the journey started slowly enough, with Nessa pipping the horn at the corners, giving one-finger waves to other drivers who had pulled into gateways to let them pass, but once they met the two-way road that followed the crease of the valley, she seemed to yank the car around each bend, hurling it over the humpback bridges.

“Please, Nessa, slow down,” Ruth murmured to her sister from the back seat. She didn’t really want her to hear, or to admit to anyone that she was feeling sick. It seemed wrong to voice her own needs at a time like this. She looked over at Rich, gazing quietly out of the window in the passenger seat, and she curled her fingers around her seatbelt. Heat built up in the car as they approached the town and she watched the steamy prints of Nessa’s hands blooming and fading on the steering wheel.

“I’ll come in with you, right?” Nessa said, swinging them swiftly into a parking space outside the oncology center. “I’ve got a list of questions for the doctor.”

Rich climbed out of the car and stretched his arms above his head. “The more the merrier.” He grinned, as if it were a party ahead of him, not a pronouncement on the rest of his life. Ruth stood beside him and reached for his hand. He’d been so frightened on their first trip here, at midnight, after their party at the end of term. He’d held a bucket between his knees then, and he’d rocked and groaned the whole way. Now, as they made their way along the corridors, he seemed to be giddy—high on the relief that steroids and anti-nausea medication had brought him. Giddy was better than scared, Ruth reckoned. She was terrified herself and glad to have Nessa with her, striding purposefully ahead of them into the consulting room. Someone, she thought, needed to concentrate on what was being said.

Ruth was actually thinking about hair, whether Rich would look old or broken if he lost his blond curls, and why her own hair, reflected in the windows, looked so much like a nest of spider’s legs or a bulge of weedy foliage. Dr. Ahmed’s hair, she noticed, was sleek and black, pulled into a gleaming chignon. She looked worthy of the serious facts that lay hidden in the file on her desk. Ruth felt too mad to comprehend them, too ugly to make sensible plans on Rich’s behalf.

Dr. Ahmed showed them a patch of darkness on the brain scan. The tumor was sitting, she said, on the brain stem itself. Crouching, Ruth thought, not sitting. She was almost offended that Dr. Ahmed would use such a dull word to describe something so horrible. She glanced at Nessa, scribbling away in her book, and hoped her notes were closer to the truth. A menacing shadow lurking on the scan.

Rich leaned forward. He was wearing a Hawaiian shirt, pink with silhouetted palm trees, and he smiled at Dr. Ahmed. Ruth noticed a tiny quiver in his jaw.

“There will be chemotherapy, I suppose,” he said.

Dr. Ahmed folded her hands. Ruth thought about her kitchen, the way the lids of her Tupperware boxes spilled out of the cupboards if she opened them too suddenly. It made her laugh, usually, or swear in creative ways. Now she wondered if others would begin to think badly of her. People undergoing chemotherapy had to live in spotless homes to eliminate the risk of infection. Nessa, in particular, would suspect her of failing Rich on this.

Dr. Ahmed put a hand to her perfect hair and explained that there would be no chemotherapy in Rich’s case. She said that although there were treatments he could undergo to reduce the size of the tumor and to make the rest of his life more comfortable, what they really needed to consider was a plan for his palliative care. She let her eyes rest on each person in turn, to check that her message had been understood.

Ruth doubted that the comprehension was evident on her face. She was holding her mouth too rigidly, her tongue dry against her teeth. It came to her that this was all her fault. She had never let Rich rest. He was first out of bed each day, and if she heard Ollie stamping or shouting downstairs she didn’t always go to help. Every morning was a rush for him—no clean cups for his coffee, his clothes crumpled in the washing basket, Ollie calling for fingertip checks of his socks lest the toes had turned crispy or any threads had come loose. On a good day, Ruth told herself there was something glorious in the chaos, but what if Nessa was right, and it was merely a symptom of her failure? What if, by hiding in her sewing room in the mornings, drawing up designs for a new sofa cover or searching out embroidery threads on eBay, she had scuppered him? She had withheld her everyday support and he had withered under the strain.

Rich turned to her and stroked her knee. His jawline quivered as he smiled. “It’ll be all right,” he said.

She put her hands to her face. “How can it be? You’re going to die.”

He didn’t want to know how long he had left. He said he would take a walk in the sunshine while Dr. Ahmed gave her estimates.

No, Ruth wanted to say. Don’t leave me with this on my own. Her breath stuttered in the hollow of her hands and she wanted to say it over and over—no to the illness and no to the dying, to her stupid jumbled thoughts about her hair and the state of her house. But she didn’t dare with Nessa’s eyes on her. She’d always told Ruth she was a quitter and it was true that, as a child, she’d been the one to faint in assembly, then later, as a student, the one begging for extensions in the tutor’s office. She had abandoned her work at the theater wardrobe not long after Ollie was born, and still she left a stack of greasy plates in the sink at the end of the day. Ruth had never been able to persuade Nessa that washing the dishes didn’t matter to her, or that her strengths lay elsewhere. What Nessa saw was Rich, rolling up his sleeves and gushing water into the washing-up bowl. She saw him dancing and whistling as he lifted the plates onto the drainer, bubbles popping merrily on his forearms, and she loved him for it. Everyone did. His blue eyes crinkled when he smiled, and he smiled all the time. He invited friends for dinner, to stay the night, to come camping with them on a sunny weekend. But he never knew if there was food in the house, any bedding for them to sleep in, or room in the car for all the tents and children he had gathered on the way. It was Ruth, supposedly so feeble, who made it all work.

Now she pictured him walking from the hospital in his ridiculous shirt, a breeze lifting the curls from his forehead. For a moment it seemed as if dying was just another of his misbegotten plans. It was almost reckless the way he had left her here in this airless room. He was keeping it all vague as usual, with only a broad fantasy of how things would be. She was the one with the details: she would have to plan it all out and make it work for everyone.