Excerpt

Wingfeather Tales

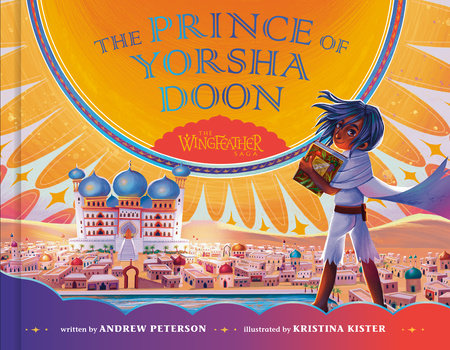

The Prince of Yorsha DoonSouth of the Killridge Mountains, west of the Chasm, north of the Jungles of Plontst, and east of the Dark Sea of Darkness lay the broad and blighted wasteland of white stone and red sand called the Woes of Shreve. The Woes were lethal. Humans couldn’t survive there because the blistering sunlight would sizzle their skin and bake their bones in a matter of minutes—none, that is, except those who managed to slather themselves with bloodrock dye, which was very expensive and very hard to come by. Hard to come by, unless of course you owned one of the few bloodrock mines that were well guarded by all manner of deadly things like assassins and mad Fangs (who survived the war) and packs of slidder vipes whose needle teeth could skin a tahala whole in the time one could say, “Oh my, I’m all out of bloodrock dye and we’re hours from shelter. It was nice knowing you.”

But there was no need to venture into the Woes of Shreve if you had the sense enough to live in Yorsha Doon. West of the Woes, on the edge of the Dark Sea of Darkness, the sprawling city of Yorsha Doon adorned the desert with bright spires and the blues and greens and purples of flags fluttering and robes billowing and turbans bobbing along the thousands of narrow streets.

Butaar music played, tahalum gruttled, merchants shouted, and children laughed in the streets, while in the nearby maze of piers, hundreds of ships creaked as waves slapped hulls and gullbirds squawked and eels shrieked. Historian and basket critic Hodar von Voodicum described Yorsha Doon as “that chaotically exquisite collision of the Doonlands.” It was hot and sandy, but close as it was to the sea, no bloodrock was needed there, and so the city was quite safe. Safe, that is, except for the clandestine guilds of thieves and assassins, the constant crush of traffic, the danger of being trampled by a tahala or lost in the labyrinth of passages and alleyways and high rope bridges slung between windows. A dagger, a steady hand, and a quick eye were quite useful in Yorsha Doon, though it must be said that not every one of the millions of people, trolls, and occasional ridgerunners was a wicked thief—some of the thieves were, in fact, quite friendly.

There in the heart of Yorsha Doon, somewhere south of Prince Majah’s palace, a boy in black leggings and a billowy blue patchwork shirt climbed barefoot through the second story window of a pleasant white building and woke a wrinkled old woman from her midday nap.

“It’s me,” whispered the boy.

“Safiki,” the old woman said as she stirred. “Where have you been?” The boy glanced out the window at the dusty city and the spires of the palace. He wouldn’t know where to begin, and he didn’t want to worry her. “All over,” he said, grateful that today she remembered who he was. Some days she greeted him as a total stranger.

“You would tell your grandmother if you were in trouble, wouldn’t you?” She lifted her trembling hand and touched his face. Her white eyes looked in his direction, but he knew they couldn’t see a thing. “Have you bathed?”

“Yes,

Mamada,” he said. What he didn’t say was that he’d done so four days ago and only because he had been hiding from the port warden.

Surely, he thought, leaping from the deck of a ship and swimming under the pier with my pockets stuffed with plumyums counted as bathing. He had at least entertained a passing thought about his grandmother’s insistence on cleanli- ness after he had climbed out of the sea and spread out on the roof of the warden’s

badaan, listening to the gullbirds and the shouts of the shipmates as they searched hopelessly for him among the many ships. The plumyums had been delicious. “That reminds me,” Safiki said. “I have something for you.”

His grandmother grinned, revealing her single tooth and her wonderful rumple of tanned wrinkles made deep and soft after years of smiling.

“I brought you this.” He removed a plumyum from one of the folds in his shirt and offered it to her with a bow of his head.

“Safiki, my dear one, you are so kind to your mamada!” She took the fruit and smelled it rapturously. “These

umamri only feed me soup,” she grumbled with a glance in the direction of the door. “What they don’t know is that I have the most fearsome tooth in all of Yorsha Doon.” She winked a blind eye at Safiki and reached into her mouth, wrenching the old yellow tooth to and fro a few times before removing it altogether with a crunch that made the boy wince even as he stifled a laugh. She wiped the false tooth on her sheets and held it up to Safiki as if he had never seen it before. The bottom end of the tooth had been ground to a point, and its edge was sharpened like a blade. “Ha!” she crowed, and then she clapped a hand over her mouth and lowered her voice to a whisper. “Your mamada could eat a flank of charred tahala rump if she wanted!”

“Then next time I will hide a whole rump of tahala in my shirt.” Safiki laughed as he sat on the edge of the bed and watched her arthritic hands make deft work of the plumyum, slicing it into tiny pieces with the tooth and popping them into her mouth. “Will one be enough?”

“Yes, my boy.” She sucked noisily on the fruity chunks. “Whatever you bring me is always enough.”

“The umamri are treating you well?”

“Well enough,” she said between slurps. “They are good people. But they don’t give me plumyums.” She finished eating, replaced her tooth, folded her hands, and faced him as if she could study his features.

Safiki adjusted her pillow and stood to leave.

“What will happen to you, my boy?”

“I’ll be fine.”

“Why don’t you stay here? The umamri will give you a home.”

Safiki sighed. “You know what I’ll say.”

“That you don’t want to spend your life in a robe, caring for old women like me?”

“I care for you, Mamada. But I would go crazy here. All they do is sing and read. My

papada was the same. You said so.”

“Ah, your

papada was a fool.”

“But you loved him.”

“I loved a fool.” Her face softened and she looked with unseeing eyes out the window toward the spires of Yorsha Doon. “A wonderful old fool. All he did was talk about everywhere else. The Killridge Mountains, the troll kingdoms, the Chasm. He never stood still long enough to see the beauty under his boots.” She closed her eyes and flexed her fingers. Safi- ki’s heart swelled for her. How many sarongs, how many turbans, how many draperies and quilts and pillow fringes had she fashioned with those hands—how many tunics and leggings for Safiki?—while her wonderful fool of a husband peddled them day after day at the markets, always re- turning home with rumors of the faraway, always with another map or sea chart? Now, her memory was fading and her sight was gone. She was too feeble to work, her husband was dead, and Safiki’s parents were dead—and all she had left was this boy who only came to see her when the noise of his conscience was too loud to bear.

“Mamada, will you tell me about my parents?”

She worked her jaw and squinted her eyes for a moment, then shook her head. “I’m sorry, dear boy. I have tried and tried to remember. But my mind is like a broken mirror. I cannot see their faces anymore. Sometimes I dream that I remember who they were, what they were like, how they died, but when I wake, the memories vanish. I was already very old when you were born, and that part of my memory is gone. That is why the umamri must care for me.”

She took his hand, and they sat for a while without speaking. The silence was broken by the sound of voices on the other side of the door.

“Go!” said the old woman, shooing him away and brushing the sheets to be sure there were no remnants of the plumyum. “And be

safe, Safiki. Find a home. Maker knows I won’t always be here to love you.”

Safiki hopped to the window and perched on the sill.

“I’ll be back soon, Mamada,” he said.

The door opened. A man and woman in white robes entered with a pitcher of water and a bowl of soup, and with a flutter of the drapes, the boy was gone.