Excerpt

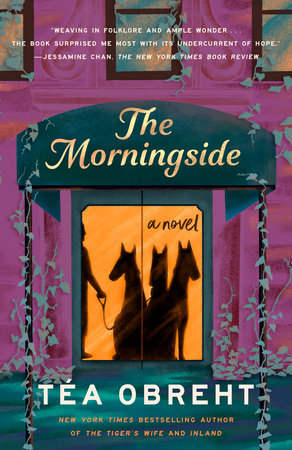

The Morningside

Long ago, before the desert, when my mother and I first arrived in Island City, we moved to a tower called the Morningside, where my aunt had already been serving as superintendent for about ten years.

The Morningside had been the jewel of an upper-city neighborhood called Battle Hill for more than a century. Save for the descendants of a handful of its original residents, however, the tower was, and looked, deserted. It reared above the park and the surrounding townhomes with just a few lighted windows skittering up its black edifice like notes of an unfinished song, here-and-there brightness all the way to the thirtythird floor, where Bezi Duras’s penthouse windows blazed, day and night, in all directions.

By the time we arrived, most people, especially those for whom such towers were intended, had fled the privation and the rot and the rising tide and gone upriver to scattered little freshwater townships. Those holding fast in the city belonged to one of two groups: people like my aunt and my mother and me, refuge seekers recruited from abroad by the federal Repopulation Program to move in and sway the balance against total urban abandonment, or the stalwart handful of locals hanging on in their shrinking neighborhoods, convinced that once the right person was voted into the mayor’s office and the tide pumps got working again, things would at least go back to the way they had always been.

The Morningside had changed hands a number of times and was then in the care of a man named Popovich. He was from Back Home, in the old country, which was how my aunt had come to work for him.

Ena was our only living relative—or so I assumed, because she was the only one my mother ever talked about, the one in whose direction we were always moving as we ticked around the world. As a result, she had come to occupy valuable real estate in my imagination. This was helped by the fact that my mother, who never volunteered intelligence of any kind, had given me very little from which to assemble my mental prototype of her. There were no pictures of Ena, no stories. I wasn’t even sure if she was my mother’s aunt, or mine, or just a sort of general aunt, related by blood to nobody. The only time I’d spoken to her, when we called from Paraiso to share the good news that our Repopulation papers had finally come through, my mother had waited until the line began to ring before whispering, “Remember, her wife just died, so don’t forget to mention Beanie,” before thrusting the receiver into my hand. I’d never even heard of the wife, this “Beanie” person, until that very moment.

For eight long years I’d been conjuring Ena out of nothing— and I’d come up with a version of her that really suited me: a tall, flowing, vulpine sort of person, generous and chuckling and mantled in benevolence. Imagine my disappointment when she turned out to be short, loud, and incredibly illpracticed at speaking to eleven-year-old nieces.

“My God, Silvia” was the first thing she said to me face-to face, standing out there by the Morningside gate with her camera while my mother and I dragged our suitcases up the hill. “Are we going to have enough rations for you?”

It was impossible to tell whether she felt I should have more or less than I was already getting. Something about her tone implied that she might be able to secure a grander breakfast than I was used to, the kind I’d only ever read about—pastries and jam, maybe even eggs. But, of course, Island City was adhering to its own version of Posterity measures, and breakfast here was a roll of the dice, just as it was in every other place we’d ever lived. Sometimes it was government tea and canned mush. Sometimes a loaf of bread and a suspect egg to share between two or three or four people. Whatever your ration card happened to say when it refreshed in the morning—assuming your local convenience store could even fulfill the request.

Ena lived in the battered little two-bedroom superintendent’s suite on the tenth floor of the Morningside. The place was furnished with scrounged items: a haphazardly reupholstered sofa, a small dining table surrounded by chairs in different states of refurbishment, a jungle of ferns and ivies Ena had found abandoned on the sidewalk and nursed back to abundance. The bay, gray and brackish, filled the view from our window. On low-tide days you could see the old freeway, which had once run just west of the building. Every now and again, a barge would get stuck between the submerged guardrails, and the whole neighborhood would descend to the waterline to watch its rescue, reminding you that the city was not as empty as it seemed.

My mother and I shared a cot in the room that had served as Beanie’s study. Our first night under that greening roof, I lay awake, watching unfamiliar lights rove the ceiling. You could have fit our whole Paraiso flat in just this room, but that smallness had felt safe. Upstairs, downstairs, all around us, neighbors had been laughing and quarreling, playing music, tromping up and down the ancient, echoing stairs. But here, the only noise seemed to come from the occasional lighthouse horn, and a strange clatter and screech that periodically sounded through the window. My mother didn’t seem to hear it, which made things worse.

I hadn’t felt the urge to make a protection for us in a long time. I was proud of that—not just because I had followed through on my decision to leave all that behind in Paraiso, but because doing so meant that I had managed to conceal the habit from my mother. For years, I had lived in fear that she would find the talismans I’d hidden around our flat, mistake them for trash, and throw them away without my knowledge, thus nullifying their effect. Or, worse, confront me about them.

“What the hell is this?” she would say. I, having imagined this precise moment, would be ready. “Looks like your old perfume bottle.”

“What’s it doing behind the stove?”

“I have no idea.”

“I could have sworn I threw it out years ago.”

“Huh.” That was meant to be my innocent, ignorant closer—because what else was there to say? “You actually

did throw it out, Mama, but I dug it out of the trash because you really loved that perfume, and Signora Tesseretti said that I need at least three meaningful objects to make a good protection”?

Anyway, that was all behind me now. The Morningside could be as looming and empty and laden with unfamiliar noises as it liked. I didn’t have three items to make a protection with anymore. I had deliberately thrown away the fragment of a photograph of a person I suspected might be my father, breaking the necessary triad. All I had left were a pair of scissors and the perfume bottle my mother had continued to spray in the vicinity of her neck long after it was empty. And I was determined that nothing would compel me to use them.

Besides, Ena was a kind of protection in and of herself. There was nothing she couldn’t explain or abate. When I asked her about the clattering and shrieking the next morning, she pointed out a huge nest that crowned the roof of a neighboring townhouse.

Rook cranes had begun migrating through the city only about ten years before, so they were still a novelty—though to even more recent newcomers like us, they seemed as much a fixture of its rooftops as the water towers where they made their nests. We had a few breeding pairs up-island, but their big rookery was sixty blocks south, in what had come to be known as the Marsh, that impassible waistline of the island that separated its upper and lower reaches, newly narrowed by the river on one side and the bay on the other. Callers to the Drowned City Dispatch radio station were equally divided between the opinion that Island City must honor its place on the birds’ migratory route and the belief that the whole flock should be exterminated. Ena leaned toward the latter view—though, in truth, she would probably have felt differently had the birds just bypassed the surfaces she was responsible for maintaining.

Anything that hindered Ena’s work was a liability. She was getting too old to serve as superintendent, and was keenly aware of it. She was prideful about her endurance, her mind stretched by the constant tally of what she had done, was doing, and had yet to do. On matters not pertaining to the Morningside, she cultivated a cool neutrality. Had she spent the past few years fervently praying that my mother and I would number among the lucky few accepted by the Repopulation Program? Not really—but she was glad we had made it. Did she have a lot of optimism about the Posterity Initiative—did she believe that ration cards and tidal mitigation and everyone pulling together would actually work, and that we would, as promised, be rewarded with a new townhouse on South Falls Island for doing our part to revive the city? Perhaps. She would believe it when she saw it. For now, she ate breakfast by the pale light of five a.m., leaning over the sink, locked in a onesided argument with those callers to the Drowned City Dispatch whose opinions enraged her the most. To supplement our rations, she foraged in the park at the bottom of our street, returning with bags full of nameless greens, which she boiled, pinned between flat disks of dough, and stacked in the back of the freezer. She smelled of metal and soap. Her right thumb stuck out from the rest of her hand at an odd angle, and when she felt like f***ing with me, she pretended she’d just broken it anew.