Excerpt

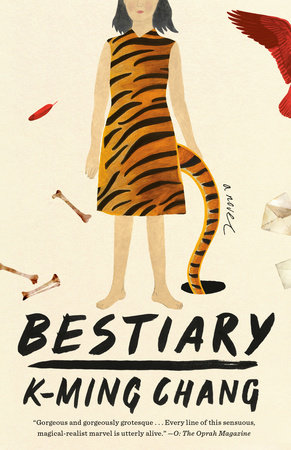

Bestiary

Chapter 1Mother

Journey to the West (I)

Or: A Story of Warning for My Only Daughter

Moral: Don’t Bury Anything.

Ba doesn’t know where he buried the gold. Ma chases him around and beats him with her soup ladle. You’ve never been to a funeral, but this is what it looks like: four of us in the backyard, digging where our shadows have died. A shovel for Ba, a soup ladle for Ma, a spoon for me and Jie to share. We dig with what we don’t want—piss buckets, a stolen plunger, the hands we pray with. We even use the spatulas gifted to us by the church ladies, after their days-long debate about whether Orientals even used spatulas. It was decided that we didn’t but that we should. Hence our collection of spatulas, different sizes and metals and colors. Ma mistook them for flyswatters. She used them to spank us, selecting a spatula based on the severity of our crime. Be glad I use only my two hands on you.

I see the way you wear your hands without worry, but someday they’ll bury something. Someday this story will open like a switchblade. Your hands will plot their own holes, and when they do, I won’t come and rescue you.

You’ve never been to this year, so let me live it for you: 1980 lasts as long as it rains. It rains the Arkansas way, riddling the ground like gunfire. Years after this story, you’re born in an opposite city, a place where the only reliable rain is your piss. You ask why your grandfather once buried his gold and forgot about it, and I say his skull is full of snakes instead of brains. He’s all sold out of memories. One time, he pees all over the yard and we follow his piss-streams through the soil. Pray they convene at the gold’s gravesite. The gold in his bladder will guide us toward its buried kin. But his piss-river runs straight into the house and floods it with fermented sunlight.

When the church wives come to give us dishes of sugar cubes and a jar of piss-dark honey, my ma tells them that Orientals don’t sweeten tea. Don’t sweeten anything. We prefer salt and sour and bitter, the active ingredients in blood and semen and bile. Flavors from the body.

Ba says he’ll find the gold soon. Ma beats him again, this time with a pair of high heels (also a gift from the church wives). Ba says the birds will tell him where he buried it all. Ma throws a flowerpot at his head (seeds via the church wives). Ba dances the shovel too deep and hits water. Except it isn’t water, it’s a sewage line, and the landlord tells us to pay for the damage. The rest of the month, we wade the river of everyone’s shit, still convinced Ba can remember, still convinced memory is contagious. If we stand close enough to him, we’ll catch what he lost.

The gold was what Ba brought from the mainland to the island. That’s how soldiers bribed the sea that wanted to steal their bodies. He paid his passage with one gold bar the width of his pinky and swallowed the rest, the gold bleached silver by the acidity of his belly.

In wartime, land is measured by the bones it can bury. A house is worth only the bomb that banishes it. Gold can be spent in any country, any year, any afterlife. The sun shits it out every morning. Even Ma misreads the slogans on the back of American coins: in gold we trust. That’s why she thinks we’re compatible with this country. She still believes we can buy its trust.

After twenty years of gambling on the island, Ba lost all the gold and tried to win it back and back and back again. When they met, Ma already had three children and one dead husband who returned weekly in the form of milk-bright rain. The local men said she was ruined from the waist down but still eligible from the waist up. She wore a heavy skirt that tarped her like a nun. Ma donated her three daughters to her parents and birthed two new ones with Ba.

I’m the second of the new ones. We’re the two she kept, brought here, and beat.

When Ma married him, he was twenty years older. Take the number of years you’ve lived outside of my body and plant them like seeds, growing twice as many: that’s the thicket of years between your grandmother and grandfather. Except Ma doesn’t measure her life in years but in languages: Tayal and Yilan Creole in the indigo fields where she was born blue-assed and fish-eyed, Japanese during the war, Mandarin in the Nationalist-eaten city. Each language was worn outside her body, clasped around her throat like a collar. Once, Ba asked her to teach him to write the Tayal alphabet she learned from the missionaries. But she said his hands were not meant to write: They were welded for war, good only for gripping guns and his own dick. Jie thought this was funny, but I didn’t laugh. I have those hands. When you were born, I saw too much of your grandfather in you: rhyming hairlines and fishhook fingers, the kind that snag on my hair, my shadow, the sky. You made a moon-sized fist at every man, even your own brother, who tried to bury you in a pot of soil and grow you back as a tree. You think burial is about finalizing what’s died. But burial is beginning: To grow anything, you must first dig a grave for its seed. Be ready to name what’s born.

Decades ago in Yilan, Ba shat out his last bar of gold, along with a sash of seawater and silt. He buried it here, in this yard we never owned and that you were born far from. Ma liked Arkansas because it sounded like Ark, as in Noah’s. All of Ma’s words are from the Bible. Most are single-syllable: Job, Ark, Lot, Wife, Smite.

The only way we’ll find the gold is if we shoot Ba’s skull open, extract the memory of where he buried it. Ma tried it once. She pointed the shotgun at Ba’s head and stomped the floorboards while saying Bang, believing the memory would evacuate from his head. Instead, Ba wet himself and Jie had to mop the floor with a dress. Apparently Ba needs a war to motivate him. Ba won’t unbury anything unless there’s a boat to be bought and married. We have a week to hire a war to come to our house. Or else, Ma says, the gold will stay buried and we’ll have fed all we own to the trees that grow moss like pubic hair.

Jie suggests we hang Ba by his feet, upside down, so that all his memories flee upstream and pool in his skull. We’d have to unscrew his head somehow. I tell her it doesn’t work that way, but Jie’s been taking anatomy lessons at the high school ten miles away, meaning she knows how to diagram a body, meaning she’s drawn me a penis with veins and everything, shown me a hole or two it could go in. She pulls down her pants so I can see. I ask her to show me where all my holes lead to, and she says if I dig into the dark between my legs, I’ll find a baby waiting to be plucked like a turnip. (Don’t worry, I didn’t scavenge for you. You were conceived the carnivore way.)

Ma shaves soft wood from our birch tree and skunk-sprays the strips with perfume to make incense, burning it in bunches. The smoke keeps mosquitos from marrying all our blood.

We pray to god and Guanyin, in that order. Pray for Ba’s gold to fall as rain or grow a hundred limbs and shudder out of the soil like metallic shrubbery.

We consider other strategies: If we borrow a bulldozer, we can flip the whole yard like a penny. But we need our money for that, and our money is buried like a body.