Excerpt

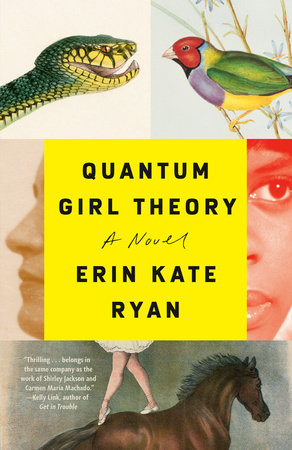

Quantum Girl Theory

Chapter 1

Spells for Sinners, Part OneBladen County, North Carolina, 1961

Mary missed her connection in Fayetteville and, still marked from the creases in the bus seat and stinking of diesel, sweet-talked her way into the pickup truck of a lanky Dublin kid headed home for supper. The boy moved to scooch his little brother out of the cab to make room. Mary patted her palm on the open window and leaned against the door to keep the younger boy from opening it.

“I like the fresh air,” she said, and tossed her twine-tied valise into the empty truck bed. She dug through her pocketbook for a scarf. “I will take a hand up, though.”

The pickup was newish, still shiny under the bus depot streetlamp. Mary settled herself atop her case and tied the scarf over her wilting French pleat. She used a folded reward poster to clean the road grime from beneath her nails, then ate a mealy apple from her pocketbook, the last of her travel food. She threw the apple core into a field of great black crows and swiveled the band of her watch—5:46. The boy was a conscientious driver and took her the whole way to the Starkings’ house in Elizabethtown. After he hoisted her down from the back, Mary offered to write a note to his ma to help explain his tardiness for dinner, to which he aw-shucks’ed and that’s-mighty-nice-but-no-thank-you-ma’am’ed. She waited for the truck to turn the corner before she approached the Starkings’ door.

Mary would normally have figured a way to take a room in town, to brush her teeth before landing on the doorstep of the family of a missing child. With her ancient broken bag, she looked the part of traveling salesman, a closer cut than she cared for. Mary slid the valise behind the grayed porch swing. A layer of lace and the reflection from the setting sun blocked her view into the front window. She caught movement, though, the brush of a skirt hem. Mary rang the doorbell.

She let up on the bell at the creak of advancing footsteps. Her hand was in her cardigan pocket, gripping the rolled reward poster. An unease was building in her gut. The door cracked open.

It was so black inside the house that at first Mary couldn’t see who had answered the door. Her eyes at last found a lined and sun-browned face wearing a neutral expression. The man, white, dressed in a rolled-sleeve work shirt, opened the door a bit wider, filling the gap with his chest. He was chewing, Mary realized, and he didn’t offer a greeting.

“Mr. Starking?” She spoke clearly, not trying to hide her New England accent. “I’m Mary Garrett. I’m hoping I can help you find your daughter.” She reached out her hand to shake his, and the man slowly returned the gesture. His palm was a deep brown in the creases, not dirty but stained, and he smelled of meat and melted butter.

“You down from Raleigh?” he said through his mouthful, hand still on hers. Mary could hear the scrape of fork on plate inside the house, a woman clearing her throat.

“No, sir. I was traveling in Baltimore and I read about your girl. I have experience with these cases, and I’d like to be of assistance in looking for Polly.” The reward poster, pulled down from a bus shelter in Richmond, noted a seven-thousand-dollar reward. Enough to set her right for three full years.

Starking held her hand still and finally swallowed his mouthful. “What kind of assistance is that?”

“I have a deep women’s intuition, Mr. Starking, and dozens of families have found my services quite valuable. With time to acquaint myself with Polly, I’ll be able to provide a great deal of insight to the case. Bring Polly home safe.” Mary no longer needed to think as she ran through her customary speech and focused instead on the tension in Mr. Starking’s jaw, fluttering like moth wings.

Starking stepped forward, crowding Mary on the porch. She minced back and pulled her hand free from his.

“You telling me you’re a lady detective or that you’re a clairvoyant?” he asked, so tall above Mary’s head that she settled her gaze on his Adam’s apple. The evening’s stubble was poking forth from his ruddy skin, sharp black hairs that would burn with hard contact, that could rub soft cheeks and necks raw from the friction of it.

“I wouldn’t put it in those terms, Mr. Starking.” But if he paid her, she’d let him call her whatever he wanted.

“My grandmama was clairvoyant,” he said over her, and palmed at his neck. “She had a real gift—burdened her tremendously. Angel at her back, she called it.”

Mary waited, hand over wrist, clasped at her waist. She shifted back to give herself more room from the man, swiveled her watch with pointy fingers.

“You can help find our Paul?” Starking’s gruffness gave way to a pleading tone.

The name hit Mary like an electric shock, a hard pinch on the bridge of her nose. A wash of warmth crept down her arms. Of course some other girl might have that name, her name, the name she’d shed fifteen years earlier when she became Mary Garrett. Mary tried to reason away her body’s reaction before she blew her chance here, but she couldn’t stop feeling the clench of resentment, of having something ripped from her. An arm thrown across her shoulder, heads tilted toward each other, a sigh of oh, my Paul, a swallowed sob.

“What’s that, Gurnie?” A woman’s voice called from inside the house, weak and impatient at the same time. The woman herself appeared in the open door, fingers smudging an empty water glass. Medium height, moderately plump, flushed pink skin, nondescript but for the grief that Mary felt swirling around her. Her housedress was stained along the skirt, and Mary suddenly saw the tumble of the gravy boat as the woman’s fingers lost feeling when she noticed she had set a place for her daughter at the dinner table. A flickering newsreel behind Mary’s eyelids, the vision lasted less than a second, but it gave her the beat she needed to recover.

“Mrs. Starking, ma’am,” Mary began, extending her hand. “I—”

The man, Gurnie, held out his hand to keep the woman behind him. “You seen my Paul?” he asked, leaning toward Mary. “You get dreams? Visions? You see her?” His voice deepened as he bent, until he nearly swallowed the final word. His demeanor, more expressive now than when he’d opened the door, was still controlled.

My Paul. The sour smell of his dinner turned Mary’s stomach. “No, sir, not yet. I’ll need some time with you, that’s why I’m here—” Mary stopped as she heard the woman draw a breath.

“What’s this?” the woman asked, twisting her hands on that water glass, looking mostly at the man. “There’s news?”

“Bernice, Mrs. . . . Garrett, was it?” He looked back for confirmation. “Says she’s got the Sight and might could find our girl.” His voice broke on the word girl, and he straightened and leaned back to the chipped clapboard siding. “My brother—”

“Lord, not this story, Gurnie,” Bernice said. She tugged at his shirtsleeve. “God knows I don’t have it in me for this right now.” A plea in her tone shortcut to the whole of their relationship—Gurnie with the wild hairs, Bernice with her deep desire for calm, for happiness in measured teacups. Bernice won most of the time. Mary didn’t need a vision to see that.

The text from the reward poster nearly a poem to Mary now, so many times she had read it: Polly Starking, last seen six days back in camp shirt and dungarees, riding a horse from the family farm out past Jones Lake. Horse found, girl missing. The overexposed photo: soft smile breaking a wide face, a short dark pixie cut, white browline glasses tipped up and to the right of the yearbook’s photographer. Exposing a tender neck, still pliant and plump as unkneaded bread dough. While worrying at the poster in Fayetteville, Mary had gotten a flickering vision—the horse, swampy and flustered, wandering the trail alone—that she’d followed all the way to this barely-there town. She was unlikely to get anything more without a visitation to the girl’s room, an interview with her parents, a chance to shut out the other noise and focus her mind on Polly. At least half the time, the parents offered up the missing girl’s bed for the duration; at others, she was happy to accept a nest of blankets in the parlor. But she’d been without success the past few months, and her savings had dwindled to less than eight dollars.

Nauseated and road-weary, Mary needed time to ingratiate herself; she needed the offer of hospitality to be their own idea. Otherwise, they would expect too much too soon.

“I don’t mean to impose on your time so late in the evening,” Mary said, voice smooth as glass. What a distance there was, between her ragged insides and her measured demeanor. “Why don’t I make an appointment to come back tomorrow a little before lunch? I can telephone, if you’d like. I’ll just be staying at the motor inn over”—she took a stab—“near the bank.”