Excerpt

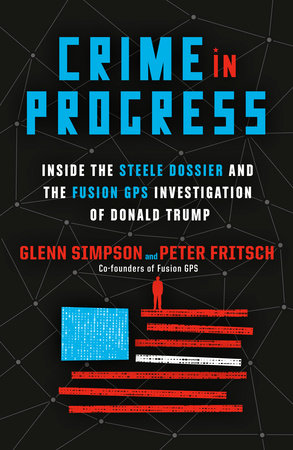

Crime in Progress

CHAPTER ONE

“I THINK WE HAVE A PROBLEM”

The surest sign the dam was about to burst came in the form of an encrypted call, on the afternoon of January 4, 2017, from a number in the 646 area code. A New York cellphone. Glenn Simpson and his business partner at Fusion GPS, Peter Fritsch, had been getting their share of blind calls since Donald Trump’s election.

The inauguration was just weeks away, and reporters from all the major media outlets were desperate to catch up on a story many had fumbled or simply ignored: how to explain the bizarre relationship between Trump and Russia.

By then, Simpson and Fritsch were deep into that story. Few outside of a small group of journalists and lawyers knew of their work during the campaign, but word had started seeping out after Trump’s upset victory. Their Washington-based research firm had been digging into Trump’s ties to criminal elements in the United States and Russia since September 2015. Month after month the project had grown in scope, starting with a review of his business record and expanding to a full excavation of his many dubious real estate projects, from Panama to Azerbaijan. Fusion worked with a global network of sources and sub-contractors to examine Trump’s dealings with an array of oligarchs and convicted criminals from the former Soviet Union as well as his decades of mysterious trips to Russia in pursuit of real estate deals that never got off the ground.

Fritsch swiped his phone to answer. “Hello, Peter?” a voice said. “This is Carl Bernstein.” The legendary former

Washington Post Watergate reporter was now working with CNN. He had something urgent to discuss. Bernstein was polite and affable, far from the aggressive, take-no-prisoners reporter Fritsch imagined from

All the President’s Men.

After exchanging a few pleasantries, Bernstein said he wanted to discuss some information he came across that suggested Trump might be entangled with Russian president Vladimir Putin in ways virtually no one knew or even suspected. If true, Bernstein said, this was a situation as dire as Watergate—maybe more so. He was also eager to get to a former British spy working at a company based in London called Orbis. He asked if Fritsch could help put him in touch.

Fritsch, a former

Wall Street Journal reporter and editor, fished a bit, trying to gure out how Bernstein had known to call Fusion. Hardly one to give up a source, Bernstein made vague reference to mutual friends. “I’m pretty sure what I’m hearing is more than just rumor,” he said.

Then he got to the point. He had heard some documents existed that painted an alarming portrait of the ways in which Russia may have compromised the incoming president. Could Fritsch help flesh out his understanding, off the record? Could he help him get in contact with the ex-spy who had produced the documents? Fritsch answered in general terms that, yes, Trump’s relationship with Russia was important, but he begged off any deeper discussion. At least for now.

After hanging up, Fritsch called Simpson on an encrypted line. Simpson was wrapping up a year-end holiday in Mexico. “Hey, I think we have a problem,” Fritsch said. “I think Carl Bernstein may have Chris’s reports.”

Chris was Christopher Steele, a former intelligence officer with Britain’s MI6 who once served in Moscow and went on to run the spy service’s Russia desk. A highly respected but low-profile Russia expert, Steele was about to become famous in ways he never expected. “Ugh,” Simpson said. “That’s not good.”

After delving into Trump’s Russia dealings for nearly nine months, Fusion had hired Steele in May 2016 to supplement its research. By then, Fusion had many reasons to harbor suspicions about the Trump campaign. Months earlier, they had uncovered court filings in Virginia seeming to show that Trump’s campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, owed tens of millions of dollars to Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch who wanted his money back and had close ties to Putin. Simpson and Fritsch had also gotten wind of a closely guarded secret: The FBI suspected that the Russian government had hacked into the computer system of the Democratic National Committee. Fusion began to wonder if these events were related.

Steele’s task was to tap his Russian source network to answer some nagging questions arising from the information on Trump that Fusion had already gathered: Why had Trump made so many trips to Russia over the years, without ever getting a single development project off the ground? Why did so many threads in the Trump story lead to Moscow and figures close to Putin? And why was Trump so smitten with Putin, who seemed fond of Trump in return?

Simpson had spent fifeen years in Washington and Europe as a

Wall Street Journal investigative reporter, focusing much of his work on the emerging scourge of transnational crime. To his surprise, some of the characters from the ex–Soviet Union who surfaced in the initial phase of Fusion’s investigation of Trump were people he had written about a decade earlier while investigating Russian corruption and organized crime for the

Journal, stories Fritsch had edited while the two worked in Brussels.

Simpson wasn’t completely surprised by the news of the Bernstein call. He told Fritsch that he had recently heard from a friend at

The Washington Post that Fred Hiatt, the paper’s editorial page editor, was talking about some sensational memoranda that sounded a lot like Steele’s work.

Someone was leaking—that was clear. This had the potential to be a big problem.

The Steele reports—soon to be known as “the dossier”—were field intelligence from one of the West’s most senior Russia watchers. The memos he produced were never meant to be viewed outside of a tiny circle of people, much less shared with the public. In unredacted form, the reports could expose Steele’s sources and jeopardize lives. Steele took great care to mask those sources in his reports to Fusion. Still, the information clearly came from people with extraordinary access in Russia, and Russian intelligence could figure out who they were and track them down. Those sources included a number of people inside Russia and field operatives outside the country who needed protecting at all costs. Unredacted memos flying around among the Washington press corps risked exposing people to real danger.

Given the control Fusion had maintained over the memos, there was only one likely suspect for the leak: David Kramer, a longtime adviser to Republican senator John McCain.

At Steele’s urging, Simpson had provided a set of the memos to Kramer a few weeks after the election. This was done for the sole purpose of passing them to McCain, who would then provide them to the head of the FBI. Steele had been secretly working with FBI agents for months, trying to sound the alarm, while Simpson had provided updates to a longtime contact at the Justice Department. Still, the feds seemed to be slow on the uptake, and Steele, Simpson, and Fritsch were concerned that the information was not getting through to the top brass. An alarmed McCain had promised to fix that.

Senator McCain, still many months from a dire brain cancer diagnosis, wanted to put a copy of Steele’s memos in front of FBI Director James Comey—a decision his friend and fellow Republican senator Lindsey Graham encouraged. McCain wanted to know if the FBI was doing anything about credible information from a trusted ex–intelligence offcial in the U.K. that a hostile foreign power might have influence over the U.S. president-elect.

Simpson agreed to entrust Kramer with a copy of the Steele memos, for McCain’s eyes only, because he knew that Kramer’s dislike of Putin ran deep. While still a reporter, Simpson had turned to Kramer as a source a decade earlier for stories on Russia’s growing political influence in Washington. But Kramer’s alarm was so acute that he could easily do something rash. Lately, he had been telling associates that he still hoped to find a way—any way—to stop Trump from being inaugurated. He thought that exposing Trump’s Russia ties might just be the answer. How he planned to do that was unclear.

Kramer’s theory was about to be tested.