Excerpt

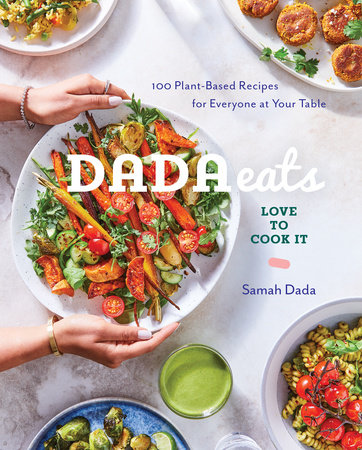

Dada Eats Love to Cook It

Introduction How can I adequately sum up what it means to me to be here, sharing with you what is not just my food, but my heart? On one level, food might look like my job. It manifests as a carrot cake with a peanut butter frosting, or hummus so smooth you get emotional. It can disguise itself as tahini used with a heavy hand right to the edge of social acceptability. It is undoubtedly all of these things. But reducing food to just a merging of ingredients would be doing a disservice to myself and to you. For me, food is not simply the end result. It is my hobby that accidentally turned into a career. It is the language I taught myself so I could be better understood. It’s how I share myself with others, and ultimately how I became more, well, me.

My parents immigrated to the United States from India when they were in high school, bringing their values and respective parents’ recipes with them. Sometimes I wonder how they grappled with raising my sister and me in California after experiencing an upbringing that was so wildly different from ours. Though they instilled cultural values and practices in us both, the reality is that I didn’t grow up as part of an Indian community, and as a result, the color of my skin and my Arabic name have constantly made me feel like an aberration.

Though I had friends, it was pretty obvious that I didn’t look like the other kids in school, making it even more jarring when I brought

sukha gosht sandwiches for lunch when my peers whipped out Lunchables and Pop-Tarts. I never felt sure of where I belonged, and my only certainty at the time was that I didn’t. I was straddling a line of not being Indian enough, yet ultimately not completely American—and I often still feel that way.

To cope, I became exceptionally skilled at being an accommodating human, friend, and classmate—a perfectionist at being a perfectionist to ensure that, well, if I stuck out, at least it would be in a praiseworthy way. I was, above all, a people-pleaser. And although this innate tendency may have subconsciously given me grief back then by prohibiting myself from failing in any way, I realize now that being wired this way has led me to one of my greatest strengths. It led me to cooking, to pleasing people and their palates. Cooking has become my language for expressing my identity and my confidence in it. Nothing has ever made more sense to me.

I have taken mental notes my entire life, watching my mom cook Indian food every night, wondering if I’d ever be able to comprehend, let alone replicate, the ease with which she’d toss together unmeasured ingredients to yield an unfailingly delicious result. She has taught me so much, yet my path to cooking has materialized as much outside of the kitchen as within it. While a student at the University of California, Berkeley, I assumed the role of unofficial restaurant critic for my friends, always prepared to rattle off a ranked list of my favorite places. Looking for a place to take your parents? Impress a friend? Ethiopian food? The best ice cream? I had everyone and everything covered. I started an obscenely long note on my phone, listing all the restaurants in the Bay Area that I wanted to visit, with asterisks next to them if I had successfully made the trek. I took pride in the street cred my restaurant expertise had bestowed upon me. It was one of the first times in my life that I felt recognized for something that felt like my thing.

It was during college that I became interested in the minutiae of food as it pertained to my well-being. I started taking boxing classes, practicing yoga, and working out at the gym. I also began to pay more attention to ingredients, studied restaurant menus like they were the hottest literature around, and visited the Berkeley Student Food Collective, a nonprofit grocery market dedicated to stocking unique fair-trade health products and local produce. My appetite for information came second only to my appetite for food itself.

After my junior year at college, I moved to New York for a summer internship at CNN, following my dream of working in television. To say I consumed New York voraciously would be a gross understatement. Though my heart knew I’d return to New York again, my brain clearly didn’t get the memo. I walked miles to Brooklyn to eat Roberta’s pizza, and then a million miles in the opposite direction to get the Salted Crack’d Caramel ice cream at Ample Hills Creamery. I learned the hard way that fresh coconuts from the summer food market Smorgasburg were not worth the price, but definitely worth the photo.

I started running in Central Park, and consequently getting lost in Central Park too many times, almost beginning to enjoy the way my feet hit the pavement. I earned the coveted “local coffee shop,” the one where the baristas knowingly smile at you when you swing the door behind you, already prepared to hand over your almond milk au lait, extra hot. I tried vegan sushi for the first time—not the kind with imitation meat, but with ripe mango, avocado, black rice, and a spicy sauce that you want to drown your entire life in. I started checking all of these things off my list, all while watching my phone’s camera roll overflow with photos upon photos of food. I decided to put them on Instagram. A part of me thought no one would care, but it wasn’t for anyone else but me. My page came into existence as a hobby, and I had no intention of it being anything else.

After coming back to Berkeley with more restaurants checked off my list, I dove deeper into conscious eating and intentionally sourced food that made both my body and my soul feel good. At the same time, I ran up against an all-or-nothing mentality. If I care about what I’m putting into my body, am I not supposed to have a chocolate chip cookie? I need cookies to function, and I don’t think I’m alone in this sentiment. What about a creamy pasta or chips with queso? Is that not “good”? Who is making these rules? Why are there a million ingredients on the wrapper of this granola bar, and is it just me or do these supposedly “healthy” crackers taste like sawdust? All of these persistent questions and realizations served as the catalyst behind my desire to start developing recipes that sacrificed neither “indulgent” nor “real.” If I was disillusioned by the options I found, then I could make my own dishes, simpler ones that used whole ingredients.

After graduating from college and traveling for a month, I ended up moving to New York for my dream job in the NBC Page Program. Armed with my own kitchen for the first time in my life, I discovered that there’s a lot you can do in there, even when your arm span takes up the entire width of the kitchen itself. Any way you slice it, the demanding nature of the Page Program should have limited my capacity or desire to cook in my minimal spare hours, but it didn’t.

I would go to work six days a week, show tourist groups around the NBC studios for hours a day, work the Tonight Show, and come home to bake brownies. I’d wake up at 3:30 a.m. to get to work at 4 a.m. for my assignment at the Today show, change into my stiff Page uniform (you’d love to see it), and head to my wobbly desk in the studio’s green-room. I would book cars for our talent and escort guests from their dressing rooms to the set and proceed to come home in the afternoon to immediately blitz spinach and basil in my blender to make a five-minute pesto.

With a new set of best friends in my Page cohort to feed, I had accidentally acquired a second job that I enjoyed just as much as the dream one I had at the network. Beyond that, I became someone in my class who was known for something. I had never felt a sense of belonging like I did in this program. And while that could very well have been because I brought cookies to work every other day, I think it ran deeper than that. Cooking for others without occasion or reason gave me a sense of confidence that finally allowed me to feel seen.

Funnily enough, it was never my aim to make my recipes fall into a specific diet or lifestyle. But a lot of my dishes happen to be vegetarian, vegan, gluten-free, and dairy-free. I don’t lead with these labels because they can seem clinical or trendy—I mean, no one is calling broccoli “vegan broccoli.” The truth is, by using minimally processed and real ingredients, the results often come with the potential to satisfy a wider audience, including those who battle with dietary restrictions or simply want to follow their preferences.

The accidental plant-based energy of this book, and of my style of cooking, has been just that, an accident—but I couldn’t be more thrilled about it. These recipes represent all the ways you can be creative with a short list of ingre- dients. It’s about doing more with less. Sure, I love boast- ing that the ridiculously soft and chewy cookie you ate was mainly made up of almonds, coconut, and maple syrup. Or that the creamy pasta had no cream in it at all, but was created using just ripe avocados, fresh basil, and olive oil. It can be a flex, definitely, but it’s more than that. The fact that my recipes can be relished by individuals who never thought they could enjoy a gluten-free brownie or a slice of dairy-free carrot cake represents the inclusivity that I both chase and seek to shine on every aspect of my work. This is something that I am extremely proud of.