Excerpt

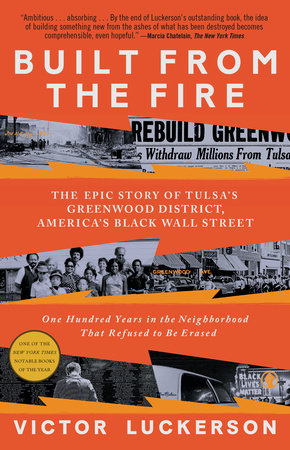

Built from the Fire

Prologue

Jim Goodwin remembers the symphony of the old Greenwood well. The blues mingling with smoke as it wafted out of hazy juke joints, the sizzle of beef on the open grill at hamburger stands, the seductive murmurs of hustlers in back alleys peddling their pocket addictions, the

click-clack of women’s heels on the sidewalk when all the maids crowded the street on their Thursday nights off. Greenwood was loud. Boisterous. It was a ritual of improvised celebration and emotional release, the same kind black people had carved out in shacks, shotgun houses, and white-picket-fence homes across this nation since our involuntary arrival on the eastern shores.

For generations, Greenwood was something more than a collection of black-owned homes and businesses just north of downtown Tulsa. Perhaps it started that way, in 1905, when Emma and O. W. Gurley first opened a grocery store north of the Frisco Railroad tracks on land once owned by the Creek Nation. But as the number of people living, loving, toiling, and thriving in the neighborhood grew, so did its mystique. George Washington Carver and W.E.B. Du Bois visited Greenwood early on, when it was, in Du Bois’s words, “impudent and noisy.” When the neon signs adorning all the cafés, nightclubs, and stately churches were lit up on warm summer evenings, folks would say it looked like a fairyland. By the time Jim was roaming the street in the 1940s, the neighborhood chamber of commerce described Greenwood as more than an avenue—“It is an institution.”

In the daily symphony, Jim had contributed his own instrument. Standing at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street as a young boy, clutching a stack of newspapers, he would yell out his sales pitch: “

The Oklahoma Eagle! Only five cents!” It was the paper his father, Edward Goodwin, Sr., purchased in 1937, just two years before he was born; Ed Sr. let him keep the money from each sale.

Jim and his siblings took on dozens of roles over the years to get the paper out the door each week. Edwyna was the first woman to serve as managing editor. Jo Ann proofread pages. Ed Jr. understood the intricacies of the printing press like no other. Daughter Jeanne penned the fiery columns quoting Du Bois and Malcolm X that reminded their father every day that he had raised black children. The Goodwins had their own internal orchestra going, anchored by the whirring of a clamorous press, one of the few in the whole country owned by a black family.

By January 2020, though, the rhythms of Greenwood have changed. Cars and semis barrel over the neighborhood on an interstate overpass that has cleaved the community in half since 1967. The monotonous clanging of bolts driving into steel beams marks the steady rise of luxury apartments occupying more and more of the area. These days Greenwood Avenue comes alive only when the Tulsa Drillers, a minor league baseball team, takes the field on land once owned by black people—some of it once owned by the Goodwins themselves, in fact. Suburbanites from Broken Arrow and Jenks drive across the roaring highway for a pleasant night out in downtown Tulsa, not even realizing they are in Greenwood. They don’t think too much about who or what might have been there before.

There are a handful of squat brick buildings from old Greenwood left standing, lined up on both sides of Greenwood Avenue as luxury towers and stadiums sprout up around them like weeds. These are managed by the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce; one other building on the south side of Archer Street is owned by Jim Goodwin and his family. There the

Oklahoma Eagle continues to publish a weekly newspaper. Neither Jim nor his children have ever taken stock of how many

Eagle editions the family has published, but an issue every week for eighty-three years equals about 4,316 newspapers.

Jet and

Ebony and the

Tulsa Tribune didn’t last as long, and most of the publications that did were acquired by corporations with headquarters far removed from the communities they covered. By holding on for so long, the

Eagle has become one of the ten oldest black-owned newspapers in the United States.

Keeping the business afloat wasn’t easy. A series of articles outlining the newspaper’s 1996 bankruptcy are framed in an office hallway labeled the “Wall of Faith.” But the

Eagle had no intention of selling out or closing down. It was entrenched on a literal cornerstone of black history. Jim often recalled a conversation he had with his father when he was still a young lawyer. “Always keep this newspaper,” Ed Sr. told him. “It will be a source of influence.”

And so the

Eagle continues to sit there, in a refurbished auto garage just off the main drag of Greenwood Avenue. Wandering its halls feels a bit like exploring the underbelly of an old church, where the gloss of the transcendent sanctuary gives way to the weary world of daily human toil. The weathered white tile floors have faded to gray. In the cavernous room, big enough to house a printing press, reams of unsold

Eagle issues and abandoned newspaper racks occupy every crevice, and stains from a weathered roof are splotched across the pockmarked ceiling.

The building has seen better days, but those days are preserved, like amber, everywhere you look. In the lobby, behind the reception desk, four large framed pictures trace the paper’s history under the Goodwins. In a bright watercolor painting, Ed Goodwin, Sr., wears a warm grin, his brightly jeweled hand covering a Bible. The jovial pose belies the many traumas he witnessed in life. His wife Jeanne, in a brown blazer, looks off frame with a sly smile, contemplating some secret she might tell you if you gain her trust. Ed Jr., Jim’s older brother and former Eagle co-publisher, wears a black leather jacket with fur lining and a brown fedora; he was always young at heart. Jim, the adult in the room since he was a child, smiles the least in his picture.

He works in an office in the back of the building, concerned more with his law practice than with the daily operations of the paper. The space certainly looks the part—plush red carpet, mahogany furniture, plaques and community awards occupying every shelf. On his desk are a brown accordion folder stuffed with case files, a Catholic pamphlet titled

Cathedral News, a bronze statue of a blind angel balancing the scales of justice, and a funeral program for Luther Elliot, Jr., an old friend who has just recently died.

Jim clacks away at emails on his computer, facing out toward Greenwood Avenue, while a West Highland white terrier named Annie scurries around his feet. He is wearing a pair of thin-framed glasses while another pair dangle from the V in his gray polo shirt. It is lunchtime. Besides the two of us, the building seems to be empty.

Shortly after I arrive, he slides a recent issue of the

Eagle across his desk. On the front page is a picture of the block outside his window, targeted in the scope of a sniper rifle. is greenwood at the crossroads or crosshairs? wonders a headline streaming clean across the width of the paper. The opening paragraph is as blunt as the illustration: “Presently, in some Tulsa boardrooms and offices, individuals are quietly discussing further development plans for the strategic gentrification but ‘legal’ usurpation of the Greenwood District.” It is one of the rare editorials in the paper Jim actually wrote himself. He once told me he was ambivalent about the changes descending upon Greenwood—he’d seen so many changes already—but the years of disregard for what neighborhood folks actually wanted wore on him. “Millions of dollars have been spent in planning of this community by residents of this community,” he says, “only to be mothballed and forgotten with the passage of each of the political influences that are in vogue at the time.”

As he is discussing how Greenwood’s story represents “quintessential Americana,” his phone rings. It’s a reporter for the

Washington Post. Earlier in the week, Jim recorded a podcast with another journalist. He’d spent decades discussing the history of his hometown for authors and documentary crews, but the interview requests are increasing now with each passing month. Over time he developed certain pithy adages that distilled his views on Tulsa, Greenwood, and race relations into fantastic quotes. The old Greenwood was a place where “on one end of the street you get heroin and on the other end of the street, you get the Holy Ghost.” Segregation was a legal and moral scourge, but it also created the underpinnings of black economic self-sufficiency—or as Jim likes to say, “What man intends for evil, God intends for good.”