Excerpt

I'll Be Seeing You

October 30, 2010

The failing of an aging parent is one of those old stories that feels abrasively new to the person experiencing it. At eighty-nine years of age, my father has begun, in his own words, to “lose it.” This is a man who was for so many years terrifying to me. He was tall and fit, a lifer in the U.S. Army whose way of awakening me in the morning when I was in high school was to stand at the threshold of my bedroom and say, “Move out.” He was never quick to smile, he put the fear of God into every young man I dated in high school, and if he said to do something, you did it immediately, no excuses. He yelled at us a lot, and, like many men of his generation, he believed in corporeal punishment. Over the years he mellowed, though he was still quick to rise to anger if the occasion seemed to call for it. But he mellowed, and none of us who really knew him could help it: not only did we love him, we liked him. The most striking thing about him was his truthfulness: the man would never lie. And he was a big softie when it came to animals and to my mother: she was the place where he put his tenderness. He had a dry sense of humor, and he was vastly intelligent.

But now. My mother says he sits sometimes with his hands over his face, unmoving, and she thinks he is depressed. Also, she has noticed things happening more and more often: a repetition of questions that she has already answered many times over. A kind of paranoia: he claims things have been taken from the glove compartment of the car he no longer drives. My mother finds him in the closet of the TV room and he says he is looking for someone who came out of there to mess with things on his TV tray. When the lid of the garbage can goes missing (after a day of high winds), he says it must be hooligans in the neighborhood—better call the police. The last time I talked to my mother on the phone, she said, “This is the best one yet. The other day, your father said, ‘What’s the matter with us? We don’t get along like we used to. Are you seeing someone else?’ ” My mother and I laughed together, but I think it’s safe to say that her heart was breaking a little, too. She said, “I asked him, ‘Have you seen my wrinkles lately?’ ”

It wouldn’t matter if he didn’t have macular degeneration and could see every line in her face. My father continues to adore my mother. Always has, always will. On every occasion that called for gifts, he lavished her with beautiful things: clothes, jewelry. On one memorable Christmas Eve, he gave her a full-length white mink coat. She didn’t want it, but how could she tell him, him grinning and taking pictures of her wearing it as she stood next to the Christmas tree? She rarely wore it after that day, and when he asked why, she said, “It’s too warm.”

They kiss when they wake up in the morning, they kiss before they go to sleep. When my father worked, they kissed when he left and they kissed when he came home. He’s a man whose mother died when he was around three years old, and he was raised by an emotionally bankrupt father and a cruel housekeeper. He found everything he needed in my mother, and that was always clear to me: she was his love. His pal. His partner. His confidante. His North Star. He does not want to be without her, not in the daytime and not at night. When I once suggested that my mother should probably have time away from him every now and then, he said, “I don’t have much time left. The time I do have, why, I want to spend it with her.”

My mother’s views are somewhat different: when my parents stayed with me in a house where the guest room had twin beds, my mother exclaimed, “My own bed!” Her absolute delight was kind of heartbreaking.

Over twenty years ago, when my father had a heart attack, it was a whopper—his heart stopped twelve times in the ambulance on the way to the hospital, and at first it wasn’t clear that he’d make it. I flew to Minnesota with a black dress in my suitcase, and went directly to his bedside. He was sleeping, surrounded by monitors, hooked up to IVs, pale in his hospital gown. When he opened his eyes, he said, “What are you doing here?” “Oh, I was just in the neighborhood,” I said, and he smiled. Then he said, “Where’s your mother?”

I have heard this question all my life. It is like a brain tattoo, my father wanting to know where my mother is, because he wants her near him always.

These days, my mother says, he follows her around the house. She will say, “I’m going in to change the sheets,” and he will come in the bedroom and watch her. She doesn’t get out much, but she does have a standing weekly date to go shopping with her sisters. When that happens, he sits by the kitchen window, where there is a view of the street, to wait for her. She brings home his dinner; he will not eat without her. She worries about what will happen if he becomes more compromised, if she cannot leave him alone.

But my father’s question, “Are you seeing someone else?” Oh, that was a good one. My mother later said, “You know, when I was in high school, I went out with Bob Harrington—I think we went to a powwow or something. And that was it. One date. I saw his obituary in the paper last week, and today your father said to me, ‘You haven’t been the same since you found out Bob died.’ ”

“Oh, God,” I said, when she told me that. Tenderly.

It was on my mother’s birthday when I spoke to her, and she said, “Your father felt so bad that he didn’t get me a gift. And I told him, ‘You know what you could give me for my birthday? Go in the den and do your Sudoku, or a crossword puzzle, or listen to one of your books on tape.’ ”

“Did he do it?” I asked.

“I don’t think so,” she said.

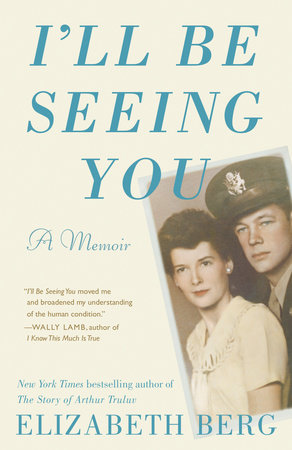

When my mother told me how bad my dad felt about not getting her a gift, I thought, Whatever was I doing that would have been more important than taking my dad out to get his wife of sixty-seven years a birthday present? I should have driven up from Chicago, or flown up, and taken my dad to the fanciest department store in town. I should have stood near him, guiding him as unobtrusively as I could; I should have said, “So whaddya think, Dad? What do you want to give her?” Apart from the full-on adoration you’ve given her since the day you met her. 1942. The back of the dime store. By the parakeets. You home on leave from the service. An introduction by a mutual friend.

Growing up with a father who was besotted with his wife lay down the gauntlet. I have not met the challenge. I failed in my marriage, and I have failed in relationships since, including the one I am in now; I fail a lot in the one I’m in now, but my partner, Bill, is patient. Sometimes I sit quietly to ponder why I have such trouble in relationships. “You just want to be free,” an old boyfriend I’d run from told me when I saw him after many years. It was true then. I guess it still is, in a way. I want to be with someone and I want to be free, too. But sometimes I look at the fantastically outsized and romantic love I witnessed all my life between my parents and I think, That’s the reason. Who could measure up?