Excerpt

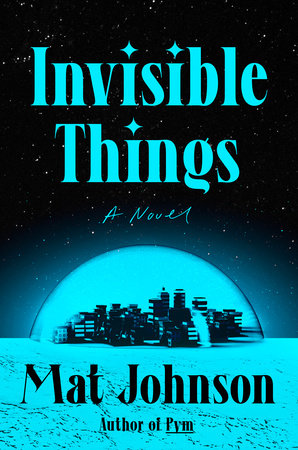

Invisible Things

Part One

Chapter 1After months in deep space conducting an intensive field study of social dynamics aboard the cryoship SS Delany, Nalini Jackson, NASAx Post-Doctorate Fellow of Applied Sociology, D.A.Sc., came to an uncomfortable conclusion: She didn’t really like people, on the whole. It was an embarrassing realization, given that her life’s work was studying them. Sort of like a dentist who hates teeth, she feared. It was incredibly isolating as well, as the universe lacked any other intelligent life to talk to.

There were several human beings, among the (likely) millions she’d encountered, whom Nalini appreciated on an individual basis, which is why she didn’t consider herself a true misanthrope. She even loved some of them, sometimes. Individually, people could be great. Studies showed that even the most antisocial primates made similar exceptions; all the data were clear on this. When feeling particularly optimistic, Nalini would advocate for the theory that, if limited to very small bands, people could even be enjoyable. In limited doses. But the unavoidable truth was that, when people were given the chance to form groups of significant size, tribalism erupted among them like recurring blisters, and thus Homo sapiens’s true nature was revealed. Because with the tribes came the bickering, the rancor, the fighting among polar opposites, the infighting among ideological twins, the rejection of empirical evidence in favor of the soothing myths and partisan lies. Nalini could list the faults of humanity all day; it was all rather predictable, but still fascinating. Sometimes, Nalini wished she could simply enjoy the study of her own species solely for the comedic exercise it was, without the haunting knowledge that these same traits would likely result in their extinction. For, though humanity had faced a myriad of existential questions over the course of its enlightenment, Nalini had the misfortune of coming of age during an era when there was really only one: Would we destroy our planet before we figured out how to escape it?

If humanity achieved interstellar migration, it could pollinate the universe with sentient life for millennia, avoiding extinction via diversification of location. If humans didn’t accomplish this goal, the only unanswered question would be which combo of consequences for humanity’s collective sins would deliver the fatal blow. Climate devastation, nuclear Armageddon, systemic xenophobia, virulent partisanship, pandemics man-made or man-fault—they were all strong contenders. The range of cataclysms was dazzling, but as an academic, Nalini was most impressed with humanity’s ability to embrace the delusion that everything was fine.

In her application for NASAx’s advertised “Open Social Science Astronautic Research Position,” Nalini proposed examining whether the Delany’s crew, consisting, as it was, of society’s most capable, intelligent individuals, could overcome humankind’s known social limitations. “Effects of Prolonged Interstellar Expedition Isolation on Group Dynamics,” she’d titled her proposal, then submitted it on a lark, inspired by hubris, free time, and a depressed job market. But someone must have agreed with the argument she made in her cover letter: that, as a sociologist with an undergraduate degree in planetary science, she was uniquely qualified to study humans beyond their Earthly habitat. This undergraduate focus was a mere vestigial tail of a long-abandoned dream that lived solely on her résumé, but it was enough to give her an advantage. Within a year, she was bidding farewell to her life on Earth—her great-aunt; her studio apartment; her younger sister, whom she didn’t really get along with—surprised by how little there was to say goodbye to.

There were so many potential career benefits to her participation in the Delany’s mission that Nalini failed to note the fact that the trip itself sounded like her worst nightmare. That this honor wasn’t another abstract academic fellowship, but something she really had to do. Something she actually didn’t want to do. On paper, cryosleep sounded straightforward, almost relaxing: You simply sleep through the most dangerous parts of the journey. But as soon as her cryopod’s lid clicked shut, it became immediately obvious to Nalini that underplaying her claustrophobia during the interview process had been shortsighted. Locked into place and still wide awake, Nalini noticed for the first time how much the pods looked like coffins. Before losing consciousness, Nalini realized she’d been snared by a branding trick: This was not “cryogenic sleep,” it was temporarily induced cold death.

Yet it was still worth it, Nalini tried to remind herself the second she woke back up. A historic mission, the first humanned mission to Jupiter’s orbit. Traversing the Solar System with a dozen crew members contained within the 7,827 square feet for over eighteen months. From a research perspective, this offered a priceless opportunity for discovery. A chance to compile the raw sociological data that might one day improve interpersonal dynamics for the long-haul space travel needed to escape the planet they were currently destroying. Or perhaps her work could even address humanity’s carcinogenic social tendencies in general. So that one day, if they ever did manage to reach another exoplanet in a habitable zone, they wouldn’t screw it up like they did their first one.

In those first weeks of floating in Jupiter’s orbit, Nalini began to fear that the crew’s wariness of her openly monitoring them would contaminate the process. But over time they grew tired of holding up their façades, just as she’d predicted they would. Nalini’s probing eyes became no more conspicuous to them than those of a portrait on a wall. It wasn’t complete invisibility—they saw her socially. Sometimes they even targeted her as the subject of pranks, behavior she referred to in her notes as “Group Masochistic Bonding.” Whenever they were successful in the act of pranking her, the perpetrators’ habit was to laugh and encourage others to laugh with them, a tool to define in-group membership. It was that signature human maneuver: forming social bonds around opposition to an almost arbitrarily defined outsider (in this case, her).

On the day-to-day, Nalini functioned as a full member of the crew. Because of the ship’s limits on physical space and weight, everything on the Delany had multiple uses and purposes—Nalini was no exception. In addition to her core mission to observe crew dynamics, she also served as an assistant to Senior Astrogeologist Dwayne Causwell, coincidentally the only individual on the ship who seemed to like her. Whereas the majority of the crew was conducting research on the planet Jupiter, Dwayne’s solitary focus was on just one of its seventy-nine moons: Europa. Its name had always reminded Nalini of some failing nightclub in Prague, but the moon was infinitely more interesting. A bruised ball of ice that hid a revelation: an ocean of liquid water just beneath its scarred crust. The moon was famous for being a possible intrasolar colonization target, but at this stage, even getting near enough to conduct drone surveys of its surface took a miracle of technology and finance. The base on Earth’s own moon was only thirteen years old and still had that new-car smell; an In-N-Out Burger on Europa was a long way off. Still, even the smallest step was a move in a glorious direction.

Researching Jupiter itself was the focus of Bob Seaford, overall mission leader, and his “band of merry pranksters,” whose idea of humor included switching the sour cream with toothpaste, then laughing when Nalini bit into her burrito. All ten of “the Bobs”—as she’d come to think of them—were from M.I.T. “The Engineers,” they called themselves (even M.I.T.’s nickname lacked imagination, in her opinion). Representing rival Caltech (go, Beavers!) was a two-person partnership consisting of just her and Dwayne Causwell, with whom she also shared the research assignment of mapping Jupiter’s most promising moon.

On paper, and as was clear to whatever algorithm assigned them to be lab partners, Dwayne was Nalini’s perfect match. Nalini was an applied sociologist with a background in planetary geology; Dwayne was an astrogeologist with a personal history of sociopolitical engagement—a rarity in his field. In addition to an alma mater, they shared the distinction of being the only crew members of African descent. They also shared an intense dislike of Bob; Nalini struggled for scholarly distance, but Dwayne didn’t bother to hide his contempt. And they both leaned on humor to combat personal frustrations.