Excerpt

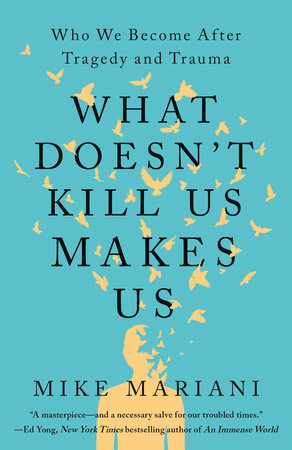

What Doesn't Kill Us Makes Us

Chapter OneDiminishment

Sophie Papp and her family had a ritual for the recently departed. Whenever a relative died, she and her brother and cousins would all squeeze into a car and drive to Koksilah River, an hour north of their homes in Victoria, British Columbia. There, they would spend the day swimming in the glassy jade water, letting the current drag them along the squishy riverbed and gazing at the native arbutus trees, whose red bark peeled like crinkly snakeskin in the summer months. On September 1, 2014, shortly after her grandmother passed away, Sophie—a sweet, reserved girl with gray-blue eyes and freckles—joined her younger brother, Alex, her cousin Emily, and a close friend. They packed themselves into a navy-blue Volkswagen Golf and headed up island to the banks of the long, twisty river.

On the way, the group made a quick stop at a Tim Hortons for coffee and breakfast before pulling back onto 1 North. That’s the last memory Sophie, who was nineteen years old at the time, has of that day. It would also be the last memory she would form for the entire next week of her life. Over the years, she’s cobbled together the facts from those who were with her in the VW that morning to create an account of what happened next.

About forty-five minutes after the stop, Emily, who was driving, spilled her iced coffee. It started dripping onto her seat, her clothes, even trickling into her shoes, and as she scrambled to clean it she let her attention slip from the highway. The car drifted to the right, eventually veering into the gravel shoulder. The sound of the tires rumbling over the carpet of rock fragments made Emily finally look up, and when she saw how far the car had slipped off the road she panicked, yanking the steering wheel to the left. The wheels struggled to gain traction on the gravel, though, and at a speed of around seventy miles per hour, she lost control. The sedan skidded across multiple lanes in both directions before somersaulting into a ravine on the opposite side of the road.

The force of the impact knocked Sophie and Emily unconscious. Hoisting themselves from their seats, Alex and Sophie’s friend were able to push the doors open and escape the mangled Golf. After around fifteen minutes, Emily regained consciousness, but Sophie remained unresponsive. When first responders arrived at the scene, they used the Jaws of Life to pull her out of the back seat. She was immediately transferred to a helicopter and medevaced to Victoria General Hospital.

Sophie was rushed into the hospital’s trauma center, designated for treating the facility’s most severe, life-or-death injuries. The large, high-ceilinged room was filled with beds, ventilators, and defibrillators; snakelike surgical lights swooped overhead and bathed the metallic tables and color-coded medical cabinets in bright fluorescent light. Within an hour, Sophie’s parents arrived. After rushing through the automatic front doors and heading for the trauma center, they were met in the hallway by a grave-faced cluster of doctors, nurses, and paramedics attending to their daughter.

During the accident, Sophie had suffered a traumatic brain injury. At the crash site, EMTs gave her a score of six on the Glasgow Coma Scale, indicating profound trauma. She had also fallen into a coma. Standing in the trauma center, her parents, who were both doctors, canvassed their daughter frantically for any signs of encouragement. Instead, they observed how her body had assumed an unusually stiff posture—arms ramrod straight against her sides, hands tightly clenched, toes flexed upward—with minimal response to stimuli. They both knew this condition, called decerebrate posturing, was a frightening sign, one that often suggested severe and potentially fatal brain damage. Neither, however, acknowledged their observation to the other. Instead, they sat on either side of Sophie’s hospital bed, stroking her curly brown hair and gently gliding their fingers over her arms. “Sophie, Mom and Dad are here,” they whispered, unsure whether their reassurances were getting through. “You’re going to be okay.” They’d both developed the emotional poise required of physicians navigating the chaos of ER departments, and that self-possession helped during those immeasurably bleak, desolating hours. Underneath their masks of composure, though, they were scrabbling to absorb the worst day of their lives, scanning their daughter’s motionless body and desperately hoping she would survive.

Sophie was eventually wheeled to the intensive care unit, where she would spend the next several days. Initially all but lifeless, she grew increasingly restless as she fluctuated between varying states of consciousness. Though still in a coma, Sophie would thrash around in her hospital bed, pull at her IVs, and mumble indecipherably to herself. At one point, while still unconscious in the neurology wing’s ICU, she even attempted to stage an escape from her hospital room. Wresting off her wires, pulling out her tubes, and dragging herself out of the disheveled bed, she clambered over the rails before collapsing onto the floor.

Her mother, Jane, remained by her side nearly twenty-four hours a day. Though non-staff were technically not permitted to stay in hospital rooms overnight, Jane found crafty ways to evade the hospital’s rules, and often slept a few feet from Sophie’s bed, on a faux-leather chair that converted into a cot. By her fourth day in the hospital, Sophie was moved to the neurology wing and placed in an acute care unit that specialized in brain injuries. Her condition had stabilized somewhat, but her physical state remained disconcerting. Behind the glass walls of her private room, she was hooked up to a snarl of medical equipment: Wires measuring heart rate and oxygen saturation dangled from her body; an IV delivered a steady stream of fluids through a butterfly needle in her forearm; and nasogastric tubes snaked through both her nostrils, which reminded her mother of a “very disturbing” plastic bull-ring. She thrashed under the hospital bedding, and her legs were often splayed at odd angles over a rumpled tangle of papery white sheets. Because she tugged at her wires and tubes so often, staff tethered her hands to the bed railings with wrist restraints.

But Sophie survived those precarious first few days, when the extent of her brain damage was entirely unclear and her stiff, contorted posture evoked her parents’ worst fears. By the end of her first week in the hospital, she was gradually emerging from her coma, her mind surfacing in short, erratic bursts. Sophie would awaken for brief, bleary snatches, offering monosyllabic responses to her parents and nurses—her first three words were “blanket,” “pee,” and “head”—before slipping back into a fretful, tumultuous sleep. Due to a phenomenon in the brain called neural storming, her body temperature swung dramatically, and staff cooled her down by wrapping cold compresses around her legs. When she got too hot, she fell into episodes of delirium, growing agitated and disoriented and sometimes even hallucinating conversations with people who weren’t in the room. Still, she was starting to communicate regularly with the family, friends, and staff checking in on her throughout each day, something her parents found extremely heartening. Sophie, it would seem, had been spared a traumatic brain injury’s grimmest scenarios.

As Sophie moved into her second week at Victoria General Hospital, though, her convalescence began to assume more perplexing qualities. Just days after regaining the most rudimentary communication skills, she was engaging in extended, in-depth conversations with everyone around her. “One day she spoke a sentence, and then not long after, she was talking endlessly, about everything,” Jane recalled. She asked staff how old they were, whether they had children, what their most interesting cases had been. She peppered doctors with questions about both her condition and their personal lives. She slipped effortlessly into sincere, heartfelt exchanges with the floor’s nurses’ aides.