Excerpt

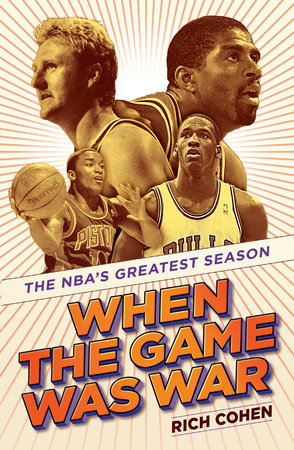

When the Game Was War

Pre-GameYou wouldn’t think a single basketball game could turn a person into a fanatic, but that’s what happened. Of course, it wasn’t just any game. It was Game 6 of the 1988 NBA Finals. I was nineteen years old, and the Los Angeles Lakers, the great and godly Showtime Lakers of Kareem and Magic and Worthy, were trying to deliver on their coach Pat Riley’s promise, made twelve months earlier in a champagne-filled locker room, to repeat as NBA champions. But it was looking like Riley was about to make a fool of himself: By Game 6, the Detroit Pistons, the so-called Bad Boys made up of Isiah, Laimbeer, and Rodman, were threatening to spoil the Lakers’ dreams of a repeat.

It was clear the oddsmakers had underestimated Detroit, a team that had thwarted two dynasties, one of the past (the Celtics) and one of the future (the Bulls) on their way to the finals. The Pistons, up three games to two in the best-of-seven series, were looking to finish off the Lakers in their own arena, the “Fabulous Forum,” in front of their own celebrity fans, which in this world is akin to getting stomped in front of your parents.

I spent the afternoon preparing for the game by playing one-on-one, twenty-one, and HORSE in the driveway with my father, a Brooklyn-born basketball coach and the man who taught me to admire the Pistons. “L.A. is class and flash,” he explained, “but Detroit knows how to win.”

Having spent his childhood on outdoor courts in Bensonhurst and Coney Island, he recognized in the Pistons what he called the “playground” or “Brooklyn” style. He demonstrated this style during our driveway contests by moving me around with his butt, hitting from the same spot again and again, and getting into my head by spewing a series of not-very-nice comments about my mother and my manhood. “Hey, Mama’s boy. I think you’ve got a little drool on your collar. Want me to get Mama to wipe it up?”

He recognized the same ethos in the Pistons, and that’s what he admired. There were no easy layups against Detroit. That team made certain that, when morning came, you’d remember you’d been in a fight. They lived by the Avenue X maxim: “If we ain’t gonna beat you, we’re at least gonna beat you up.”

It did not hurt that the Pistons were led by 27-year-old Isiah (Zeke) Thomas, who was not only great-looking and charismatic but was also, in the relative terms of the NBA, small. Five-ten in shoes, Isiah was a short man in a tall man’s game, which meant, my father explained, he did not have to be merely as good as the others; he had to be better. Most fans today don’t remember Isiah as he was in the late 1980s, when he was the best player on the best team. Say what you want about Michael and LeBron, but, pound for pound, inch for inch, grading on a curve, Isiah was the GOAT.

And he was local, a Chicago area product just like me, and so, though my home team wasn’t in the finals that year, Isiah—a short, underestimated, baby-faced Chicagoan—became my avatar. The Pistons were looking to close out the defending champions in six games, eager to inaugurate their own dynasty (they would go on to win in 1989 and 1990). Pat Riley trademarked the term “three-peat” for the Lakers, but the Pistons would have used it first had they also won in 1988, putting them among the all-time greats instead of the not-quites. Today, the Bad Boys are remembered mostly as a foil—what, in the world of pro wrestling, they call a “heel.”

That night, Isiah and the Pistons were hanging in midway through the second half, when, on what looked like an otherwise routine play, Isiah ran over the foot of L.A. guard Michael Cooper, turning his ankle ninety degrees. Isiah fell to the floor, reached for his foot, and screamed.

The Forum got quiet—it was the kind of uncanny silence only a crowd can make. Jack Nicholson was on his feet. Barbra Streisand looked concerned.

A trainer helped Isiah to the bench, where he sat, leg extended, as trainers and doctors worked all around him. The injury capped off what had been a punishing postseason for Zeke, who had been cut, tripped, banged, and knocked out over the course of the last seven weeks. The game continued. The announcer said Zeke was probably done for the night; my father—we were watching on the Magnavox in the family room—agreed. “You roll an ankle like that,” he said, “it blows up, then you can’t put any weight on it.”

Isiah, who seemingly had the same thought—I’ve got to do what I can while I can still walk!—somehow got his busted self back onto the floor. It was as if, knowing his ankle would soon triple in size, he decided that this was his best chance to push his team across the finish line.

He took an inbound pass, then went to work. Though hobbled—he moved like a supermarket cart with a punk wheel—he set up plays, delivered pinpoint passes, hit shots from all over the floor, and now and then, in that third quarter that seemed to stretch into a lifetime, even drove the basket, going one-on-one with players who were a foot taller and a hundred pounds heavier, including Magic Johnson, who had been (but would soon no longer be) one of Isiah’s best friends.

The Detroit Free Press later ran a list of all the shots Isiah hit in the third quarter.

11:01 2 free throws Lakers 56–50

10:31 Follow up 5 footer Lakers 56–52

10:06 18 foot jumper from the key Lakers 58–54

9:37 12 footer from the right side off drive Lakers 62–56

8:14 14 foot bank shot from left side Lakers 64–58

7:38 12 foot jumper on left side, from Dumars Lakers 64–60

6:22 Breakaway lay-up, from Dumars Lakers 66–62

3:29 12 foot jumper on left baseline from Dantley Lakers 74–68

2:59 14 foot bank shot from [Vinnie Johnson], Cooper fouled on play—Zeke missed free throw Lakers 76–70

1:13 26 foot 3 pointer, from Vinnie Johnson ties score at 77

0:46 Breakaway lay-up from Rodman tied 79–79

0:02 20 footer from left corner, from Johnson Pistons 81–79

Isiah’s 25-point third quarter remains a postseason record. But it wasn’t just the numbers that dazzled. It was the grit, the determination, the way this small man at play in a world of giants put his team on his back and nearly delivered them: The Pistons came up just short, and many believed they were hosed by the refs with a bad call at the end.

Isiah became a symbol in those twelve minutes, an embodiment of everything that a person who wants to live ecstatically should be. He played with fury and joy. He loved his teammates and his opponents—you could see it in every move. He never gave up, never stopped trying. He did this not in spite of his injury but because of it. As a professional athlete, he knew it would only get worse, that it was now or never, that the pain did not matter if he did not notice it, that, in this league, there is only today, this quarter, right now. He was like a protagonist out of a Camus novel—I’d taken existentialism in college that year—who is free because he knows he will die.

That’s the night I fell in love with the NBA.