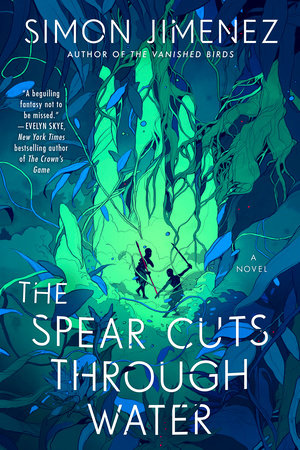

Excerpt

The Spear Cuts Through Water

Before you arrive, you remember your lola, smoking. You remember the smell of her dried tobacco, like hay after a storm. The soft crinkle of the rolling paper. The zip of the matchstick, which she’d sometimes strike against the lizard-rough skin of her leg, to impress you. You remember the ritual of it. Her mouth was too dry to lick the paper shut so she had you do it, the twiggy pieces of tobacco sticking to your tongue like bugs’ legs as you wetted the edges. She told you it was an exchange. Your spit for her stories. Tales of the Old Country; of ruined kingdoms and tragic betrayals and old trees that drank the blood of foxes foolish enough to sleep amongst their sharp roots; any tale that could be told in the span of one quickly burning cigarette. “It was all so very different back then,” she’d begin, and you’d watch the paper curl and burn between her fingers as she described the one hundred wolves who hunted the runaway sun, and the mighty sword Jidero, so thin it could cut open the space between seconds. Her words forever married to the musk of her cigarette and her bone-rattling laughter; so much so that whenever you think of that place, long ago and far away, you cannot help but think of smoke, and death.

When did she first tell you of the Inverted Theater?

You were thirteen, you think; it was around that age that she often seemed startled by you, offended even, her lip curling whenever you came into the room, as if an untoward stranger had just tripped into her on the street. You thought her distaste was because of your body odor, your oily skin, your shy hunch, but the truth was she was just surprised by how quickly time had passed. Your youth wounded her. It made her want to protect you, and to kick you out the door.

“Sit,” she said, when she saw you passing the kitchen. “Listen. I have a tale to tell.”

The warm, breeze-blown night came in through the propped-open window, playing at the sheer curtains and the smoke from your lola’s fingers, as she told you of the theater that stood between worlds.

“Once, the Moon and the Water were in love.” She lingered on that word, love, just as the smoke lingered in the air. “You can imagine it was not the most convenient affair. One was trapped in the heavens, the other the earth. One was stillness itself, the other made only of waves and tempests. But they were happy for a time. The Moon would bathe the Water in its radiance, and the Water would dance, with its ebb and flow, to the Moon’s suggestion. And though they occupied different spheres, they were able to visit one another through less direct means, for there is no barrier in this life that love cannot overcome. The Water would send up to the skies plump storm clouds, swollen with its essence, its cool mist and salty breath kissing the Moon’s dry and cracked surface. And the Moon, when it wished to visit the Water, would cast its reflection into the Water’s surface, and in the Inverted World that lies suspended below our own, in glass and still water, they would meet, and dance, and make love.” Your lola paused, and stared at you from between curls of smoke, in study of your expression. There was a time when you would be squeamish at the mere hint of intimacy in her tales, but not this time; this time you simply sat in rapt attention—a sign of maturity that both heartened and depressed her. “Anyway,” she said, after a rasped inhalation. “It was in that world of reflection where they built the theater that is the locus of our tale.

“Being the patron gods of artists and dancers, the Moon and the Water both loved the stage, which is why they created their own: a pagoda so tall its height cuts through the heavenly bands, within which the performances of the ages would be hosted. The telling of tales beyond even my knowing.” She coughed. “Even after the Moon and the Water parted ways, the theater remained, run by their love-child, a being of immense beauty who took to inviting even mortals such as us to come visit their arena.”

You asked her how mortals could reach such a place.

“Through dreams,” she said, the cigarette butt ash in her hand. “A deep sleep, in waters deeper than your dreaming spirit has ever swum before. That’s all. Dreams, and luck. And when you arrive, you are told a tale of the Old Country; the right tale at the right time. And when you leave—when your body comes up from that deep slumber—you will feel satisfied, whole, though you will not remember why, the memory of your visit forgotten, slipped from the mind like soapy water, the way any good dream might the more one tries to recall it. You will try to remember it. With great effort.” She smiled, wistful. “But you will fail.”

Your lola began rolling another cigarette.

“Perhaps before the end,” she said, “I’ll finally remember my own time there.”

There was giggling from the other room. As your lola worked the tobacco through the rolling paper, you leaned back in your chair to better look at your brothers, who were listening to the radio in the living room. All nine of them were crowded around the radio like stray cats at a butcher’s shop—a leg draped over the arm of the couch—a head lolling off the side of the love seat—chins propped on fists on the coffee table as the weekly serial neared its climax—all of the inquisitor’s men aiming their rifles at the church windows, ready to shoot Captain Domingo dead, wondering as they aimed down their sights why the jackal dared to smile at the hour of his death—the reason clear, once the good captain revealed with a wink the detonator in his gloved hand—and as you looked at your brothers, you felt both envious that you were not sitting with them and also glad that you were apart from them. That you could see them all from your chair in the kitchen. That you could hold them all in your eye and keep them there.

“We might try to go back,” your lola said, staring out the window with her large, wet eyes, “but we only get one turn. One invite. So do not waste it. If nothing else, remember that.”

The night air came in through the small kitchen window. A horn from an old car blared down the road. Your father would be home soon with the day heavy on his shoulders. The table still needed to be made. But your lola was unconcerned with time, her drags deep and unhurried. “You will not know the Inverted Theater has called for you until you are already there,” she said as she let the paper burn, and the years burn with it. “It is a place you cannot plan for.” The shutters trembled against the coastal breeze. “And when you arrive, dream-tripped and unexpectedly, in that amphitheater, the best thing you can do is sit, and watch, and listen, for you are not there by accident.”

She sucked on the paper, the tip now an orange rose. The cigarette was just about finished when the front door slammed open. Your brothers scattering from the radio as your father came inside with his mood and all the outside world—your lola gripping your wrist, before you too could go to greet him.

“The tale is for you,” she said.

The tobacco burning in her lungs.

“So let the dreaming body go.”

She exhaled.

And the smoke, blown in from the dark, envelops you until all you can see are the curls of gray matter swirling around you, the thick fog seeming to lift you, to cradle you, bearing you gently downward until you light upon a smooth, hard surface, and the smoke clears—the memory of your lola in the kitchen fading as day does to dusk, before you find yourself standing before the very place she had once spoken of, all those years ago.

Welcome to the Inverted Theater.

You step out of the smoke and you see it: the towering pagoda on a still lake at night, its reflection in the water perfect, its many levels at once rising high above you and, in its watery likeness, falling endlessly below. Lanterns hang off its curved eaves like earrings, lighting up its ornate facade against the darkness of the black-carpet sky. The structure looms, made up of an infinite stack of balconies, each one painted a different color. From a purple balcony high up a herald leans over and shouts that the performance is soon to begin, to please enter and take your seat.

A stone path begs you to cross the dark water. As you begin your crossing, you realize you do not walk alone. You walk amongst a river of other dreaming shades, who pass through you like gusts of wind, their thoughts coming in and out like radio signals. They are thinking about work. About lost loves. The hours they wasted in rooms darkly lit by stubbed tallow candles. I was keeping the books for a madman. I knew I needed a new job, but I couldn’t risk the downtime—who can risk the downtime? Some you understand, others are beyond you. They speak in languages you do not recognize, or in terms that, stripped of context, mean nothing. Thread-ripping down the runner of stars, was in the midst of my third weft, fast a-tumble in my sleeper’s mitt, when my dreaming self was coaxed here, to this dark lake shore. Shades of people from everywhere and everywhen. Faceless, out of focus, loud. And as you cross this lake, their noise comes all at once and overwhelmingly, sounding like nothing less than the vast ocean’s roar—a collective hum, breathed out by the mouths of thousands, indistinct and infinite. An infinity in which you now sit.

Eighth row, dead center.