Excerpt

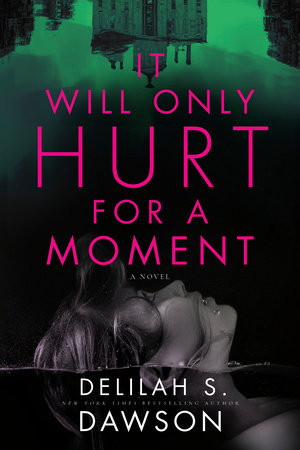

It Will Only Hurt for a Moment

1The leaves have not yet begun to turn, but the mountains hold their breath. Sarah Carpenter has been driving for three days, from Denver to north Georgia, past craggy peaks and flat cornfields, chaotic cities and verdant forests, and she still can’t relax, can’t stop checking her rearview mirror to see if she’s being followed. The map says she’s only half an hour away from her destination, and if her informational packet was accurate, she’ll lose all signal soon and have to navigate solely based on the directions she scribbled off the website. Slightly terrifying, but also the point. When you’re running away from someone, it’s best to be utterly inaccessible.

Her phone rings from its stand on the dashboard of her crossover, startling her. It’s an unknown number, an area code she doesn’t recognize. She normally wouldn’t answer it, but right now, she’s not leaving anything to chance. If someone besides Kyle is trying to find her, she needs to know why. When she mashes the green button, she is further startled to realize that she’s now on speakerphone—because yes, of course, her phone is hooked up to her car’s audio system.

“Hello?” she says, over-loud and annoyed.

“Sarah?”

The voice blaring through her car’s speakers is like nails on a chalkboard, and Sarah has to jerk the wheel to stay on the winding mountain highway. Gravel grinds under her tires in perfect tune with her grinding teeth.

“Yes, Carol? Is something wrong?”

“You haven’t called. You should call more. Kids are supposed to take care of their mothers. Tit for tat.”

If Sarah wasn’t driving along a treacherous road overlooking a deep fall into a sweeping valley, she would close her eyes and pinch the bridge of her nose, where a small but persistent, familiar pang has begun to throb.

She hasn’t called her mother in five years, and her mother hasn’t called her. When she moved out west, it felt good, leaving Carol behind in Savannah. Sarah knows that addiction is a sickness, not a choice, but she still refuses to forgive her mother for choosing alcohol. Given the option to go to rehab and remain in her only living relative’s life, Mom dove deeper into the bottle. And she doesn’t even drink good wine.

Judging by the fact that she’s calling and her voice is slurring, Carol has not stopped drinking—or gotten treatment for whatever sickness is nibbling at the edges of her once-sharp mind.

“Is there a problem?” Sarah asks again. “This isn’t your phone number.”

“Mine got turned off. Jean let me borrow hers. I always remember your number. Where are you?”

Sarah looks at the cracked blacktop ahead, winding under the summer-gold trees. She doesn’t want her mother to know where she is. There’s a chance she might tell Kyle, and then . . .

“What do you need, Mom?”

“I wanted to know what I should bring for Thanksgiving. Jean will drive me over to your place, but I can pick up a pie at the store, first. You always liked sweet potato.”

Sarah realizes she’s not breathing, top teeth sunk into her lower lip. She wants to scream at her mother, remind her what a failure she is, how horribly her mother’s drunken outburst and arrest at a River Street bar messed up both of their lives, how they don’t speak. She wants to tell her that she moved across the country to Denver five years ago and after hitting the block button, it was a revelation, never having to see her mom’s phone number flash up on her phone a single time. She wants to tell her about Kyle.

But none of it matters. Her mother wouldn’t remember it. If she was able to understand, she’d just say that the breakup was Sarah’s fault for not being a more supportive girlfriend. That’s another deep wound—when Dad was alive, Mom always treated him as her top priority. First Dad, then Chardonnay. Then work, volunteering at the animal shelter, church, that phone game with all the little diamonds, watching golf on TV. Sarah is always last.

“We’re not doing Thanksgiving together,” Sarah says. “You do it at the assisted living center.”

“Their turkey is always dry,” Carol complains. “I prefer a ham.” There’s a pause where the sound of an old woman sipping wine from a coffee mug fills Sarah’s car like thunder. “Where are you?”

Nowhere. Sarah is nowhere. She’s on her way to somewhere, on her way to the only thing that’s felt like hope in years, but she’s not going to tell her mom that. The thing about a broken brain is that all sorts of things slip through the cracks. Maybe Carol remembers Kyle’s number, from when they’d just started dating. Maybe she remembers how to get on Facebook. Maybe she accidentally tells someone where Sarah is going.

It’s none of her business. When she chose the bottle, she chose a life apart.

“Driving,” Sarah says, as she’s not a good liar.

“You should come get me,” Carol whines. “I want to look at cars.”

“You can’t drive, Mom. They took your license. Don’t you remember going to jail after you assaulted an officer?”

Carol’s voice is tentative and cagey. “What? Jail? Me? Of course not. I just can’t find my wallet right now. This place you put me in is full of thieves.”

It’s the nicest place in the area, which her mother can afford thanks to a fat inheritance from her teetotaling parents. The license is in Sarah’s bag, hidden in the pages of her planner. The old woman has no excuse to be on the road. Sarah should’ve hidden her keys long ago, before she put Lucy Zimmerman in a coma and slapped an officer.

“Bye, Mom,” Sarah says, deflated and tired.

“No! No! You listen here. I’m your mother. You—You leave me in this dump, you never call, you won’t give me grandbabies. Won’t even invite me over for Thanksgiving. I raised you! Gave you a good life! I did the best I could. And this is the thanks I get?”

The speech would be a lot more dramatic if Carol hadn’t yet again paused to take a slurping sip.

But Sarah is done. She’s made a clean break from her old life, and she might as well sever the last tendon, even if her drunk mother will forget they ever spoke.

“Mom, you were a shitty mother. You’ve always been a drunk. You promised you would quit, and you never did. You knocked your best friend off a barstool and broke her skull because she tried to take your keys. This is the first time we’ve spoken in three years, but you don’t remember because in addition to the drinking, you’re developing dementia. You’re toxic, and we’re done.”

There’s a gasp, and then her mother starts sobbing. Sarah blinks back her own tears, waiting breathlessly to see what her mother has to say to the truth she can only express because she’s three hundred miles away and already on the run.

“That’s crazy,” Carol finally says. “You’re crazy. None of that is true at all. You just don’t want me at Thanksgiving.”

“I’m hanging up now.” Sarah reaches for the phone.

She’s done being called crazy.

“Honey, wait. I need to tell you something.”

Sarah pauses, her fingertip hovering over the red button as she struggles to stay in the lane. The line is quiet, nothing but an old woman’s labored breathing. There’s a rough dirt turnoff up ahead, the kind blocked off with a rusted gate that probably leads to someone’s hunting land, so she pulls off the road and parks. She can’t focus on staying between the lines when she’s this upset. Whatever her mother says next, it’ll be over soon, and Sarah can go back to pretending that Carol doesn’t exist, just like she’s learning to pretend that Kyle doesn’t exist.

There’s a terrible weight to this kind of grief, to letting go of someone who’s still alive but not who they used to be, maybe not ever who you thought they were. It comes back like migrating birds, stupidly descending again and again to feed on skeletal bushes already stripped of berries. It leaves Sarah so, so tired, so emotionally barren, talking to her mother.

Maybe she’ll push the button anyway.

It’s not like her mother will remember.

She never does.