Excerpt

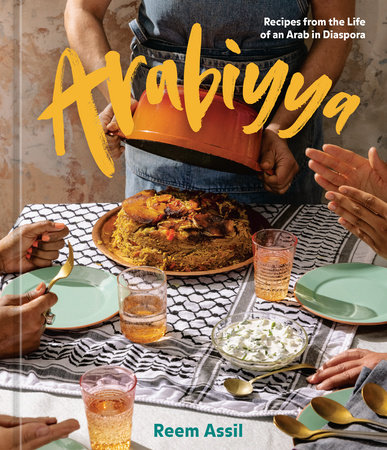

Arabiyya

IntroductionI was born in Waltham, a little town twenty minutes outside of Boston, in the hottest month of the year. Forty-eight hours had gone by since labor pains had interrupted my mother’s birthday picnic beside the cooling breezes of the Charles River, where she had spread a blanket to behold the July Fourth light show. She often pointed out the irony of a birthday greeted each year by the haunting sound of pyrotechnics. A child of war, my mother had fled Gaza, Palestine, in 1967 only to land in the crossfire of an oncoming civil war in Lebanon that would fully erupt several years later. Fire-filled skies were nothing new to her.

Growing up, whenever I put up a fight, she was quick to remind me of her long, hard labor, and that from my very birth, I insisted on doing things on my own terms. Crossing the street as a toddler, she’d tell me I needed to hold her hand. “I’ll hold my own hand,” I would reply, clasping my hands in front of me.

From the time I could sing, I picked up refrains from Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got to Do with It” and Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach,” sending ripples of discomfort through my Syrian father and Palestinian mother. From their telling, I never chose the easy way. When I was upset, our entire apartment complex would hear about it. Neighbors reported that my cries could be heard from the McDonald’s parking lot across the street. Sympathetic to the struggles of new parents, they laughingly called me the neighborhood terrorist. It never occurred to my parents to take offense.

My parents started me on toasted pita for teething and garlicky hummus as my first solids. However, my own earliest food memory was not of these Arab staples but rather of eating chocolate cake with my first crush, my neighbor and best friend David. Dressed only in Pampers, we dove into that cake headfirst, bathing ourselves in frosting, sucking fistfuls of the sweet goo from our hands.

One day, after learning that David’s family had moved away, I escaped from our apartment to sob at the foot of his door, where I’d so often gone to find him. Soon after, we, too, would move.

My parents chose Sudbury, a woodsy suburb known for its outstanding schools and its role in the American Revolutionary War. Our home was nestled in the historical footpaths of American legends such as Babe Ruth, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau and served as a perfect staging ground for my magic shows and theatrical performances. In elementary school, I won a starring role as Mary Poppins in the first-grade play and tested my parents’ patience, practicing the songs from the moment I woke in the morning until lights-out at night. It was my dream to broadcast into people’s living rooms like Julie Andrews.

Inside our home, my parents established a strong foundation of Arab culture. But outside, the customs of our well-to-do, largely white town inevitably won out. I learned to code-switch at an early age. While we spoke Arabic at home, we were encouraged to speak only English in school. Early on, my teachers pushed my parents to switch to English, worrying that my reading and writing would fall behind. My sister often joked I switched into my “white voice” on the phone or in the store, when I wanted to blend in: upbeat and high-pitched, demonstrating good vocabulary, and offering a disarming smile, especially when someone pointed out I had a “slight accent.” I learned American idioms such as “the cat’s out of the bag” and tried to use them correctly. Every once in a while, I would mix them up, as in “I can read him like the back of my book.”

I planted a foot in both worlds. One weekend, I’d slip into my Girl Scout vest to sell cookies door-to-door, followed by memorizing verses of the Quran with my father on the way to Sunday school. The next weekend, I’d sneak into parental controls to watch Salt-N-Pepa’s “Let’s Talk about Sex” on MTV and later ride along with my uncles to live orchestral concerts to hear iconic Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife’s brilliant political ballads saluting Palestine.

My food memories are etched with morning bowls of Kix cereal and afternoon snacks of Chips Ahoy! cookies dipped in milk; the only time you’d find me over a stovetop was to boil instant ramen packets and to make Kraft macaroni and cheese from a box. These memories also include long potluck dining tables, extended with desks and folding tables dragged in from other rooms, stacked with olive oil–drenched mezze dips, mountains of rice, cardamom-scented ground meat casseroles, herbed salads, and, inevitably, a box of supermarket cookies added by a family that had run out of time.

By high school, identity began to weigh large. My Arab features and olive skin tone were mistaken for every imaginable ethnic identity—from Indian to Puerto Rican. Though I didn’t develop race consciousness until college, my awareness of racial injustice was born at Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School. We were but a handful of Brown kids. While I felt uncomfortable being misidentified, I was even more fearful of saying where my family came from. I had few friends and spent lunch, book in hand, nestled into a corner of the cafeteria, lost in a world created by George Orwell and other grimly imagined futures that matched my mood.

My distress was lifted by teachers of color, few though they were, and one lefty Jewish teacher from the Bronx, whose obsession with Jack Kerouac inspired field trips to New York to hit the highlights of the Beat Generation. Taking his lead, I helped organize a trip to the Deep South, visiting places that had changed the course of American history—from Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three civil rights workers had been murdered, to Birmingham, Alabama, where a church bombing by the Ku Klux Klan had killed four young Black girls. Meeting with civil rights activists and hearing their stories helped channel my angst. I learned to question the world and imagine how I, too, might help make another, better world possible.

In each place, I became more enraged at America’s legacy of white supremacy and more inspired by people who put their bodies on the line for nonviolent resistance. I began to make connections between the conditions in Mississippi and Gaza, the Montgomery bus boycott and the Palestinian intifada, and the forced migration of Black folks from the South and my own parents’ migration from Palestine and Syria. I wanted to be like the changemakers who inspired me on that trip.

I set off for college, hoping to solve the issue of “peace in the Middle East.” I felt a new sense of possibility, and I even told my professors that I would become the first Palestinian Muslim woman president. But soon, I recognized a familiar discomfort. Diplomacy, I learned, mostly meant maintaining US influence over the fate of countries like the ones I came from. With anti-Arab fervor erupting following the September 11 attacks my first week of college and with war looming, I fell into a deep despair. I feared for the safety of Arabs both in America and in our homelands. I couldn’t imagine how it might feel to experience justice in the midst of such darkness (and cold Boston winters). I dropped out of school and found my way to sunny California. Like many before me, I fell in love with the Bay Area for its diversity and rich history of social movements. I discovered that you could actually get paid to knock on a door, walk inside, drink some tea, and inspire someone to stand up to a local corporate landlord to lower the rent. To be a part of that transformation was life-changing.

When I was not at work, I was helping transform a decades-old Arab political nonprofit into an organizing hub for working-class Arabs. Through it, I built my own Arab community. We made the streets of Oakland and San Francisco our second home, amplifying our power through bullhorns, calling for an end to the US-backed war and occupation of Iraq and building deep alliances with like-minded Black and Brown activist groups. My mother has often jokingly reminded me that when she used to visit, her itinerary often involved locating me at the intersection of a protest march route.

While I honed my skills as an organizer, I also built the kind of community I had always yearned for on a soccer team that proudly called itself anti-imperialist. On the field, I met my husband, an impassioned literacy educator, along with other teachers, artists, cultural workers, and activists, each contributing to social change in their own way. We built up our running skills to evade the police in the city’s anti-war street protests and countered burnout with laughter, dance parties, and mountains of home-cooked food.

For self-care, I built an aptitude for mental calculus and straight-faced trash talk through playing poker. I represented my league at the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas and dreamed of going pro. And, at the very same time, I fell into Buddhism at Oakland’s first people of color–led Buddhist center.

Yet none of these things, even when put together, fully satisfied me. Throughout my ups and downs, between episodes of burnout and heartache, I gradually recognized that working with food had become a source of emotional, even spiritual, comfort. The sense that food might provide a vehicle to connect me with my life’s purpose grew, and I recognized I needed to find ways to explore it.

So, I left my job as an organizer to see whether life as a baker might nourish my spirit and connect me to my ancestors.