Annie Hartnett is the author of

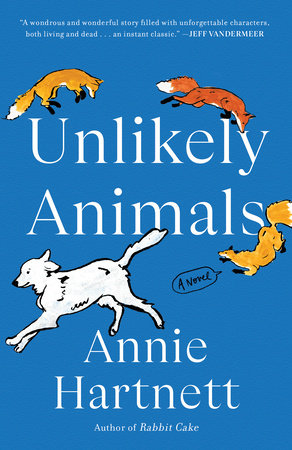

Unlikely Animals, which won the Julia Ward Howe Prize for fiction and was longlisted for the Joyce Carol Oates Prize.

She is also the

author of

Rabbit Cake, a finalist for the New England Book Award and a

Kirkus Reviews best book of the year. Hartnett has been awarded fellowships and residencies from the MacDowell Colony, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Associates of the Boston Public Library. Along with writer Tessa Fontaine, she co-runs the Accountability Workshops for writers, helping them commit to routines and embrace the long, slow, joyful, terrible process of doing the work. She lives in Massachusetts with her husband, daughter, and dog.

More by Annie Hartnett