Excerpt

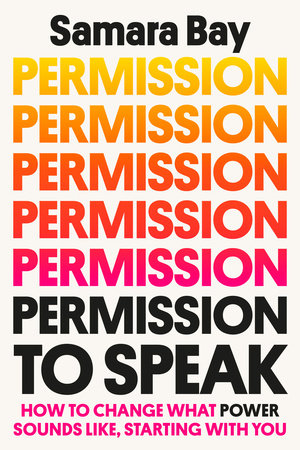

Permission to Speak

1Breath

I am willing to be seen.

I am willing to speak up.

I am willing to keep going.

I am willing to listen to what others have to say.

I am willing to go forward even when I feel alone.

I am willing to go to bed each night at peace with myself.

I am willing to be my biggest, bestest, most powerful self.

These seven statements scare the absolute shit out of me. But I know that they are at the crux of it all.

—Emma WatsonHold on a second and just breathe. There’s the regular ol’ in-and-out rhythm that prevails while we sleep or perform mundane tasks; maybe you feel it now. And then there’s the sort of breath that accompanies moments of true surprise in our lives—a warm touch, a punch line, the unexpected sighting of a friend. The rhythm changes and we take in more air than usual. It’s an instinctive response to what’s new and original. It’s the moment I read aloud the pregnancy test pamphlet to my husband to figure out the symbol on the little stick—and stopped mid-word with a gasp. It’s the shaky sigh that followed, full of possibility and pure vulnerability. This breath is life on the move.

But breath is something else too. For almost a decade, “I can’t breathe” has been a rallying cry against the policing of Black bodies, a reminder of how easily a delicate windpipe—or a human—can be mishandled. And when the coronavirus hit, desperate cries for breath resounded in hospitals around the world, in every language humans speak. In order to avoid getting sick we locked ourselves away from others and covered our noses and mouths to literally keep our breath to ourselves. Gathering in a public space, mingling our aspirations and inspirations together, had become dangerous. That very first weekend of the lockdown in the United States, I remember sitting up in bed reading everything I could. Hyperventilating. Thinking, My God, sharing breath might now mean death.

Against this backdrop, it’s no small thing to start to notice your own breath, in trivial moments as well as in moments that scare the absolute shit out of you. Breathing is the easiest thing to do; it sort of just happens, like blinking. And breathing is the hardest thing to do when you’re taking a risk, when that in-breath is preparing to let a feeling or an idea from inside of you out, and the outcome is uncertain.

But in a way, sharing these breaths in public has always been dangerous. For those of us with fresh perspectives who are inevitably drawn to question conventions, the public has never entirely welcomed our feelings or ideas. We’ve been threatened and discredited and ignored. We’ve lost our jobs and been tried as witches. We’ve not been believed. For anyone outside traditional positions of power, to take a deep breath and speak requires undoing thousands of years of messaging about who gets to have a voice in public and how they get to sound. There’s a whole mythology to reckon with.

Because here’s the deal: when you take a real and full breath, air from outside your body is sucked in and then emerges a fraction of a second later as you—as your hopes and dreams, your furies and joys. Your demands. Of course we each need air simply to stay alive, but we each need air to activate our furies and joys as well, and we must activate them if we want to change the story—it’s how we reshape the mythology about who gets to speak in public and how they get to sound. It’s how we become our own new heroes. My dream for you is that when the stakes are enormously high, you step into the moment ready to breathe deeply and let yourself out.

But sometimes we find ourselves in rooms where we are the only one—the only member of our race, or the queer community, the only woman, only person in a wheelchair, only one wearing flashy colors or secondhand clothing or visibly pregnant or speaking with a different accent or willing to lose money to do what’s right. Sometimes we find ourselves in an arena that’s not designed for us to conquer, as Black Lives Matter activist Tamika Mallory says. That’s when we feel the deep desire to shrink or hide our difference, and a great way to accomplish this disappearing act is to stop taking real breaths.

But sometimes that room is due for a renovation—and maybe you’re feeling up for blueprinting the new design. I’ve seen it over and over, with the clients I’ve coached, with outsiders on big stages everywhere: we are ambitious and bold, on a mission and powered by purpose, primed to conquer the world. But then we get up in front of those whose lapels we are so ready to grab, and . . . we hold our breath, forcing air through a constricted throat that’s trying to both let us out and keep us in. We speak, but we stifle, and our voices come out raspy or flat. We sound halfhearted. We’re ready to change the story, but our voices haven’t gotten the memo. Maybe we’ve braced ourselves for so long—against not belonging, not being enough, against being misunderstood, discounted, or booed off the stage—that we do it now out of habit. And those lapels remain untouched.

I am here to help you break this habit, which is as much about giving yourself permission as it is about reacquainting you with your breath. You have to trust, truly trust, that your body belongs there, and invite yourself into spaces that scare you, wholeheartedly. This kind of trust takes practice, and I’ve got exercises that will help you get there.

And I’ve got some perspective, too, because you are not alone. You are not the only one who senses you don’t belong and whose breath hitches at the thought of declaring what you believe. Our discomfort with speaking in public, which is really discomfort with being public, is a story that belongs to so many of us, and to our mothers, and grandmothers, and all the black sheep, misfits, and dreamers. None of us were invited to the table when social conventions were drafted eons ago. It helps to keep an eye out for each other now, to notice the other “onlys” and make them feel welcome, allow them to breathe easier. Let yourself imagine us as a collective, let the camaraderie dance on your cheeks, and when you catch each other’s eye perhaps you will see your reflection and breathe easier yourself. There’s nothing like the power of solidarity to pick up the pen and rewrite old conventions. For all of our sakes.

When Vice President Kamala Harris accepted the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in the summer of 2020, she was at times fiery, at times playful. She was conversational and intimate but also drummed up the weight of ceremony and spoke with purpose. It’s worth rewatching as a master class on breath. She starts with “Greetings, America!” in a room devoid of the buzz of a crowd, without any of the organic feedback politicians relied on in a pre-pandemic world. But she nonetheless takes in a hearty breath before speaking further—as though breathing in everyone who has helped her get to that stage, as though breathing in her own sense of belonging. She could have shortchanged herself and sped on ahead without breath support, but she didn’t. “It is truly an honor to be speaking with you tonight,” she proceeds, breathing again after this thought. She centers herself with this pause, and uses the air to prompt the next thought, and the next.

You could call this pacing—but I don’t care about a measured tempo. I care that you’re breathing for the thought you want to convey, and for the people who need to hear it—which means that you must be present enough to continually read the room and read yourself. Some statements call for a deliberate delivery with silence at the end so the meaning can reverberate as you look out at your expectant audience. Maybe even a full cycle of breath, in and out and in again, before proceeding. Silence and nothing but a room breathing can be surprisingly powerful. But some statements deserve a hastening rhythm because the momentum itself lends meaning to the statement—often near the end of a speech or the end of an argument, as you build triumphantly toward your conclusion. And you can accomplish this with a speedier, more athletic in-breath. Kamala did it all: she took up space, she honored her message with the right-sized breath for the size of her thoughts, and she was deeply, keenly present.

When we take responsibility for our breaths like that, we have a shot at fully showing up. We have a shot at creating moments of true surprise, life on the move. Rebels take deep breaths; in fact, I believe we need breath support in order to rebel. Deep breaths allow us to be audible and visible in our full glory. Deep breaths allow us to bring our whole, human selves into rooms that may not be ready for us and then teach them what they’ve been missing. That’s what changes the story.

And so, this first chapter in a book about the voice is actually about the quiet moment before there’s a voice. It’s about the moment when you’re about to step onstage and you tell yourself, Breathe! only to find that you lift your shoulders or puff out your chest and your body responds with more panic, not less. It’s about the moment you reach the mic, look out at your audience, and shortchange yourself by attempting to breathe into a body too sticky from stress or habit to accept the full breath. Or the moment you hold your breath in anticipation and then forget to let it go. It’s about everything that can go wrong and how swiftly, with a bit of help, it can go right.