Excerpt

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau

Chapter 1

CarlotaThey’d be arriving that day, the two gentlemen, their boat gliding through the forest of mangroves. The jungle teemed with noises, birds crying out in sonorous discontent as if they could foretell the approach of intruders. In their huts, behind the main house, the hybrids were restless. Even the old donkey, eating its corn, seemed peevish.

Carlota had spent a long time contemplating the ceiling of her room the previous night, and in the morning her belly ached like it always did when she was nervous. Ramona had to brew her a cup of bitter orange tea. Carlota didn’t like when her nerves got the best of her, but Dr. Moreau seldom had visitors. Their isolation, her father said, did her good. When she was little she’d been ill, and it was important that she rest and remain calm. Besides, the hybrids made proper company impossible. When someone stopped at Yaxaktun it was either Francisco Ritter, her father’s lawyer and correspondent, or Hernando Lizalde.

Mr. Lizalde always came alone. Carlota was never introduced to him. Twice she’d seen him walking from afar, outside the house, with her father. He left quickly; he didn’t stay the night in one of the guest rooms. And he didn’t visit often, anyway. His presence was mostly felt in letters, which arrived every few months.

Now Mr. Lizalde, who was a distant presence, a name spoken but never manifested, was visiting and not only visiting but he’d be bringing with him a new mayordomo. For nearly a year since Melquíades had departed, the reins of Yaxaktun had been solely in the hands of the doctor, an inadequate situation since he spent most of his time busy in the lab or deep in contemplation. Her father, however, didn’t seem inclined to find a steward.

“The doctor, he’s too picky,” Ramona said, brushing the tangles and knots out of Carlota’s hair. “Mr. Lizalde, he sends him letters, and he says here’s one gentleman, here’s another, but your father always replies no, this one won’t do, neither will the other. As if many people would come here.”

“Why wouldn’t people want to come to Yaxaktun?” Carlota asked.

“It’s far from the capital. And you know what they say. All of them, they complain it’s too close to rebel territory. They think it’s the end of the world.”

“It’s not that far,” Carlota said, though she only understood the peninsula by the maps in books where distances were flattened and turned into black-and-white lines.

“It’s mighty far. Makes most people think twice when they’re used to cobblestones and newspapers each morning.”

“Why did you come to work here, then?”

“My family, they picked me a husband but he was bad. Lazy, did nothing all day, then he beat me at night. I didn’t complain, not for a long time. Then one morning he hit me hard. Too hard. Or maybe as hard as every other time, but I wouldn’t take it any longer. So I grabbed my things and I went away. I came to Yaxaktun because nobody can find you here,” Ramona said with a shrug. “But it’s not the same for others. Others want to be found.”

Ramona was not quite old; the lines fanning her eyes were shallow, and her hair was speckled with a few strands of gray. But she spoke in a measured tone, and she spoke of many things, and Carlota considered her very wise.

“You think the new mayordomo won’t like it here? You think he’ll want to be found?”

“Who can tell? But Mr. Lizalde’s bringing him. It’s Mr. Lizalde who’s ordered it and he’s right. Your father, he does things all day but he never does the things that need done either.” Ramona put the brush down. “Stop fretting, child, you’ll wrinkle the dress.”

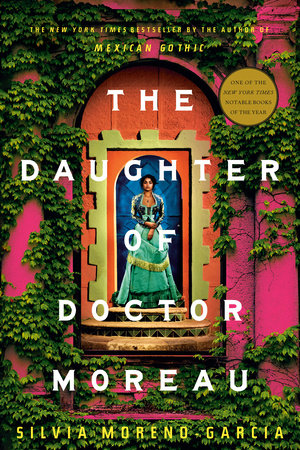

The dress in question was decorated with a profusion of frills and pleats, and an enormous bow at the back instead of the neat muslin pinafore she normally wore around the house. Lupe and Cachito were giggling at the doorway, looking at Carlota, as she was primped like a horse before an exhibition.

“You look nice,” Ramona said.

“It itches,” Carlota complained. She thought she looked like a large cake.

“Don’t pull at it. And you two, go wash your faces and those hands,” Ramona said, punctuating her words with one of her deadly stares.

Lupe and Cachito moved aside to let Ramona by as she exited the room, grumbling about all the things she had to do that morning. Carlota sulked. Father said the dress was the latest fashion, but she was used to lighter frocks. It might have looked pretty in Mérida or Mexico City or some other place, but in Yaxaktun it was terribly fussy.

Lupe and Cachito giggled again as they walked into the room and took a closer look at her buttons, touching the taffeta and silk until Carlota elbowed them away, and then they giggled again.

“Stop it, both of you,” she said.

“Don’t be mad, Loti, it’s just you look funny, like one of your dollies,” Cachito said. “But maybe the new mayordomo will bring candy and you’ll like that.”

“I doubt he’ll bring candy,” Carlota said.

“Melquíades brought us candy,” Lupe said, and she sat on the old rocking horse, which was too small for any of them now, and rocked back and forth.

“Brought you candy,” Cachito complained. “He never brought me none.”

“That’s because you bite,” Lupe said. “I’ve never bitten a hand.”

And she hadn’t, that was true. When Carlota’s father had first brought Lupe into the house, Melquíades had made a fuss about it, said the doctor couldn’t possibly leave Carlota alone with Lupe. What if she should scratch the child? But the doctor said not to worry, Lupe was good. Besides, Carlota had wanted a playmate so badly that even if Lupe had bitten and scratched, she wouldn’t have said a word.

But Melquíades never took to Cachito. Maybe because he was more rambunctious than Lupe. Maybe because he was male, and Melquíades could lull himself into a sense of safety with a girl. Maybe because Cachito had once bitten Melquíades’s fingers. It was nothing deep, no more than a scratch, but Melquíades detested the boy, and he never let Cachito into the house.

Then again, Melquíades hadn’t liked any of them much. Ramona had worked for Dr. Moreau since Carlota was about five years old, and Melquíades had been at Yaxaktun before that. But Carlota could not recall him ever smiling at the children or treating them as anything other than a nuisance. When he brought candy back, it was because Ramona asked that he procure a treat for the little ones, not because Melquíades would have thought to do it of his own volition. When they were noisy, he might grumble and tell them to eat a sweet and go away, to be quiet and let him be. There was no affection for the children in his heart.

Ramona loved them and Melquíades tolerated them.

Now Melquíades was gone, and Cachito slipped in and out of the house, darting through the kitchen and the living room with its velvet sofas, even stabbing at the keys of the piano, ringing discordant notes from the instrument when the doctor was not looking. No, the children didn’t miss Melquíades. He’d been fastidious and a bit conceited on account of the fact that he’d been a doctor in Mexico City, which he thought a great achievement.

“I don’t see why we need a new mayordomo,” Lupe said.

“Father can’t manage it all on his own, and Mr. Lizalde wants it all in perfect order,” she said, repeating what she’d been told.

“What does the mister care how he manages it or not? He doesn’t live here.”

Carlota peered into the mirror and fiddled with the pearl necklace, which, like the dress, had been newly imposed on her that morning to assure she looked prim and proper.

Cachito was right: Carlota did resemble one of her dollies, pretty porcelain things set on a shelf with their pink lips and round eyes. But Carlota was not a doll, she was a girl, almost a lady, and it was a bit ridiculous that she must resemble a porcelain, painted creation.

Ever the dutiful child, though, she turned from the mirror and looked at Lupe with a serious face.

“Mr. Lizalde is our patron.”