Excerpt

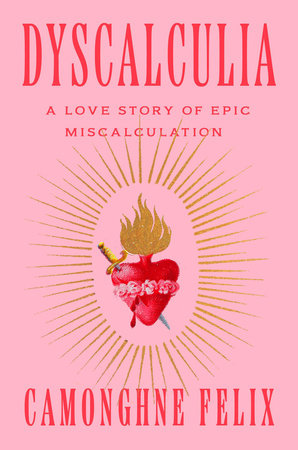

Dyscalculia

As it turns out nature has a formula that tells us when it’s an entity’s time to die.

There’s even an equation for it, where size becomes rule and the laws of expiration must obey: take the mass of a system of organisms (a species of plant, all mammals); its metabolic rate (read: speed of entropy) is equal to its mass taken to three-fourths power.

Pythagoreans believed that numbers were an infinite, invisible, but radically real force in an ultimate but uncreated world of exponentially dynamic beings.

They believed that numbers, and to what rhythms we assign them, give birth to the ineffable, to the faithful. This is how we learn to hear beauty, how we come to know the nature of deficits, how we know what it means to be full, what it means to offer an abundance, and how to quantify the sin of greed.

This faith is what introduces the doctrines of Plato, and through Plato, Aristotle’s incarnations, and through that translation, western consciousness is born, and through western consciousness come these varying systems of order, these strange phenomena of persuasive appeal, then the Self gained a title, lending western civilization a way to feel, a way to comprehend the sequential mechanics of how each individual comes to know for certain their place and purpose in the world.

Of all artistic mediums, mine of choice is one of mathematical impulse, lyrics buoyed by the universal truth of the one and the two.

When I say I wanted to die, I do not mean it hyperbolically, metaphorically, or symbolically—I’m not trying to metaphorize an ache or insult the natural functioning of the mind. Memory makes me flawed in remembering, but this I can tell without mirage, without the phantasmagoria of misery.

One autonomous lonesome entity in a sea of other entities one day ventures out of its home, in which it dwells alone, and stumbles upon its ecological double. Bonded, the two leave their lonesome habitats and choose to reinhabit the orb of the living world as some new, mutated thing. One world, meeting another, entering another anew.

What two lovers do in the room of that third world is the math of it all.

I loved him, and it gave me a fever.

Aight, so boom:

The morning after his birthday, we lie lazy in the deep cusp of our bed, the sun’s tender touch grazing the fur of our bodies. I reach over to check the time on his phone instead of mine, mostly because his was closest, mainly because a pesky impulse primed me to look and I get giddy in my ancestors’ mischief. I press the phone’s home button to illuminate the screen, and as if summoned, one lone text flashes white across the face: “I’m so in love with you bby, I wish you were with me last night instead of her.”

At first, I smile easy at the warmth of it. I love to know the one I love is loved—a natural symptom of narcissism, or of gratitude. After a moment, a dawning flushes over me, the warm wisp of that easy morning suddenly plucked away, my pulse racing into disgust as I realize he lied, realizing I knew exactly who she was, the memory of a girl he’d curiously and opaquely befriended just a few months before projecting from my memory’s drunk archives. On my birthday she offered me a shot of a dry gin, the taste of her guilt like salt on my tongue.

I had asked him. I had asked him then, and he had lied.

Like an instant high, I feel myself losing my sense of time, colors ringing in my ears, the sun brighter than ever before. I shake him awake, shaking him, shaking him.

As he wakes, I see panic fill in on his brow. “Who?” he asks. “What? I’m in love with you, babe, c’mon!” except the tether is missing from his eye, he is lying again, right to my face, his betrothed, his promised one.

Breathing gets difficult then, and with all the ringing in my ears, thinking is an odd task. Something takes over and I lean into my autopilot, calling Her from his phone before I even know who I’m calling. She answers, and I demand precision: I want to know what, I want to know for how long.

(Okay, tea: Apparently, he had been planning on leaving me. Apparently, she had been planning on waiting it out. That whole sad time, I had been planning on becoming his wife, so none of the data aligned, the margins too muddy to reconcile.)

There’s silence. Then the crushing wail of a million mournings. Then a collapse. From a view above the room, I watch myself melt into a foolish rage as I’m being let in on a secret that had canceled me out, that made me the woman unwanted. All of a sudden, I am a child again, up in a flame I can’t stop, an anger I can’t manage.

I wanted him and I wanted him to be sorry and I wanted to be a woman who could go glamorously unaffected by such blatant ignorance, because how dare he eclipse me, make me ugly, how dare she even f***ing breathe. I wanted Her ruined. I wanted Her flattened.

And I wanted to f***ing die.

A fractal is a never-ending pattern—infinitely complex. It’s a simple equation processed over and over again, reproducing itself in perpetuity, hiding around and inside of us, like Russian dolls, like a forest bordered by and stuffed full with trees, like a river that splits and meets itself in another river, like a stamp, like your DNA, like your brain, like your lungs, like their functions.

Where any death, even the tiniest one, is the result of a patterned agitation.

It’s hurricane season. We’re standing in the warm, wet Brooklyn breeze and sharing a lucky cigarette just weeks before our final dance begins, the starry lid of the sky winking down above us.

“Tinder is so weird,” he tells me. “I keep starting conversations with people I can’t finish.”

It’s like that! I tell him. Thank god we don’t actually have to date.

He chuckles, taking a deep inhale on his drag of the cigarette.

I ask him: Have you met anyone?

I reassure him: It’s okay if you have.

“No, of course not,” he says. “You know I can’t see anything but you.”

The nobody of Certeau’s Everyman is truly common twice: once in madness, again in death.

He is leaving the home we share for the last time, and I resist this event horizon with everything I’ve got, tripping as I fumble after the tail of his shirt, arms stretched long, reaching and reaching for any inch of him, him reaching for the exit, my eyes begging for him in the heavy silence of this scandalous peepshow as my two good friends look away like onlookers to a drunken scuffle, embarrassed and slightly afraid. I pull him with me into the bathroom for a bit of humble privacy, begging just talk to me, please. I walk him backwards into the windowless washroom, begging, begging, please, please don’t go, please look at me, I love you so much. He lifts me by the waist, eyes as flat as the bottom of a steel pan, sits me on the bathroom sink, and enters me, one hand wrapped around my neck, one hand muffling my mouth. After three strokes he pushes himself away from me, his breathless release breaking suspension. I fall to the vinyl floor where I crumble into fetal and stay. From this corner of the universe, this single panel of cold tiled floor, I look up and the final scene begins to roll: the camera pans to the bent back of this man who once loved me pulling his pants up over his hips, then shows booted feet as he steps over me, then over the bathroom’s threshold and into the corridor, then pans to his fist as it grips the knob of the front door. Finally we see his face, brown and weathered and strange. He looks down at me through a shroud of tearful, dolorous pity. He whispers, “I really am sorry, I’m so sorry,” and goes.

On the other side of the freeway, traffic stalls to better observe the three-car pileup clogging the middle of the road. We slow down to get a close glimpse at the mangled metal, the twisted roofs punctuating each other with new angles and sharp lines. From where we sit, a mere twenty feet away, heads craning out of our windows, it is impossible still to know who holds ultimate fault in this tragedy, who to send the bill to. All the cars are the same color, same size, same make, 1997 white Acuras—in the end, the fault could belong to any one of them: the one distracted by her girlfriend’s rage text on the way home; the one playfully racing with the station wagon in the lane next to him; the one jerking off behind the wheel. Any one of them could be the fatal other, the one with the confession to make upon meeting their maker, but regardless, in the end, even the one least responsible for the final output had the choice of the input in hand. From over here, all of the victims are villains, and all of the villains are dead.