Excerpt

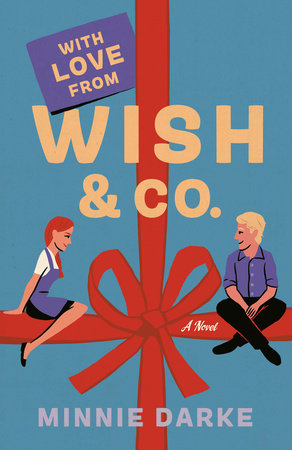

With Love from Wish & Co.

Part OneNine days before the implosion of the Charlesworth marriage Alone in the quiet of Wish & Co after closing time, Marnie Fairchild decided to give it a try. With the shop’s front door locked and the blinds drawn to shut out Rathbone Street’s evening rush, she reached beneath the counter for a magazine of a kind she did not, officially, read. Marnie wasn’t the type for crystal healing, moon-phase gardening or the study of tea leaves. But since she’d already done all the sensible, practical things she could think of to do, and none of them had worked, she was now prepared to try anything—even ‘Manifestation for Beginners’.

First, the magazine instructed,

make sure you are in a pleasing space. Marnie frowned, feeling the urge to argue. The precise problem, she wanted to tell the magazine, was that her shop was not a pleasing space. It was what had brought her to something as airy-fairy as manifesting in the first place; the very reason she had blown her grocery budget by slipping into her basket a magazine with a title like

Celestial Being. There was not, and never had been, any beholder alive who would have said Wish & Co’s rented premises were any kind of beautiful. Too old to be modern, and too young to be charmingly vintage, the shop had cheap fibreboard walls, flimsy aluminium windows, and nothing interesting waiting to be discovered under the linoleum flooring.

Marnie had done her best with paint, furnishings and taste. She’d had a wall fitted out in nicely battered recycled timber shelves, so that now, when the ladies of the eastern suburbs were hosting the kind of dinners where the candles matched the napkins, they found themselves standing at those shelves, trying to decide between the equally luscious colourways of Wish & Co’s quality party supplies. Sea Glass or Rose Quartz? Moonstone or Onyx?

In the section of the shop that was set up as a wrapping studio, Marnie had covered the walls with racks of luxury gift wrap and installed a huge, rustic table to distract from the floor. But despite all her efforts, the shop continued to prove the old saying about sow ears and silk purses.

As a gesture towards making the space more pleasing, Marnie lit a pillar candle from the Rose Quartz range and switched off the fluorescent overheads. The edges of the store softened to a circle of candlelight, and she read on.

Focus your mind. Make sure you have a clear vision of what it is that you want. Easy. For there it was, in the framed photograph she kept propped on the countertop, in all the glory of its heyday. She could see it only dimly in the candlelight, but Marnie didn’t really need to look. She knew the old shop by heart. In her sleep she could have sketched the mullioned front window with its twentyeight gridded panes of glass. She’d have been able, blindfolded, to draw the three neo-Gothic arches of the top-storey windows, as well as the ornamentations on the steeply pitched bargeboards that framed them. F

airchild & Sons was still standing, also on Rathbone Street, seven blocks away in the direction of Alexandria Park. But just barely. To Marnie’s uncle, who now owned it, the shop was nothing more than a heritage-listed irritation taking up space on a square of valuable real estate. If it hadn’t been earmarked by the council for preservation, Lewis Fairchild would long ago have had it demolished.

The place was already in a serious state of disrepair when, two winters ago, it had almost burned to the ground. The morning Marnie had woken to news of the fire, she’d flung a coat over her pyjamas and run up the street. Behind a hastily erected barricade, she’d joined local business owners and other bystanders, and watched as the brightly clad firefighters rolled away their hoses and the last twists of smoke drifted out of the broken front windows. Arson was the verdict of the investigations that followed, though nobody was ever convicted.

The shop had been saved, but every time Marnie walked past she grieved the charring on the beautiful bargeboards and the graffiti on the hoardings that now covered the main window. Her uncle seemed content to leave the old building in its dilapidated state, perhaps hoping that it would fall down of its own accord, or that a second arsonist would come along and do a better job than the first.

Marnie pulled her sleeve down over the heel of her hand and wiped a fine layer of dust from the glass of the framed picture. In her great-grandfather’s day, the store had sold groceries. When her grandfather took over the business, he’d transformed it into a high-end shoe shop, with stock both imported from Europe and handmade on the premises. This photo had been taken on the day of the shoe shop’s official opening, and the grandfather she had known less than half as well as she should have done stood proudly in his cobbler’s apron, arms crossed, in the doorway.

Archie Fairchild hadn’t lived long enough to see the opening of Wish & Co, but Marnie felt sure he’d have been proud of her, for taking the risk of starting her own business in the first place, and also for the way she’d grown it from a simple retail outlet into a diversified enterprise that included custom gift-wrapping, gift-wrapping workshops, and—most profitably—a boutique and highly personalised gift-buying service. All of which now needed a better, more substantial, more beautiful home.

Marnie breathed in the rose scent of the candle and brought her vision into focus. When the old shop was hers, the weatherboards would once again be painted in crisp, fresh white; her gift-wrapping papers on their racks would be backgrounded by traditional lathe and plaster walls; the wrapping table would stand on the kind of rustic floorboards it deserved. She would no longer have to go out the back at the end of a workday and climb metal stairs to a tiny flat with a cupboard-sized bathroom and a foldaway bed. Rather, she would ascend a circular timber staircase at the back of the shop to find herself at home in a tastefully renovated retreat, with sloping ceilings and pine floors that glowed in light softened and shaped by a triplearched window.

Now, the magazine article instructed,

picture what needs to happen for your vision to become a reality. Be very specific. Marnie closed her eyes. She would be standing at the wrapping table, wearing her gingham apron, sleeves rolled. Her mobile phone would ring and the sight of her uncle’s name on the screen would give her a little jump of excitement.

‘Lewis!’ she’d say. And he’d say, ‘Marnie, how are you?’ But they wouldn’t chat, Marnie decided. Mostly because she could not imagine anything she and her uncle would have to chat about. Instead, he’d cut right to the chase.

‘I’m ringing about Fairchild and Sons,’ he’d say. ‘It’s past time I did something with the place, and I reckon your grandfather would have wanted you to take it on.’

But was that exactly what he’d say? She was supposed to be very specific, and Marnie wasn’t sure her uncle would use a matey word like ‘reckon’. It was hard to know. She’d been in Lewis’s company four or five times in her entire life. One of those was at her father’s memorial service, which she had been too young to remember, and another was at her grandfather’s funeral, where Marnie and her mother had stood at the back and slipped out before the coffee and Scotch Fingers.

The last two times she’d seen her uncle were when she’d made appointments, through his personal assistant, to visit him at the top-notch financial advice firm Fairchild & Rooke. Both times, he’d leaned back in his big leather armchair, bow-tie askew, and failed—if he was even trying—to hide his expression of bemusement. That the daughter of his black-sheep younger brother seriously thought she was in the market to buy, outright, a property at the Alexandria Park end of Rathbone Street clearly struck him as smirk-worthy.

Both times, he’d told her he wasn’t selling. However, she had managed to extract from him a promise that he would contact her if ever he changed his mind. To keep herself in his thoughts she sent an email every month—each one slightly different, but always respectful and brief. By the time he made the phone call she was now manifesting, he would have realised that she was serious. Her persistent emails would have impressed upon him that even if borrowing the kind of money the shop would fetch would be a stretch for her, it was not an impossibility.