Excerpt

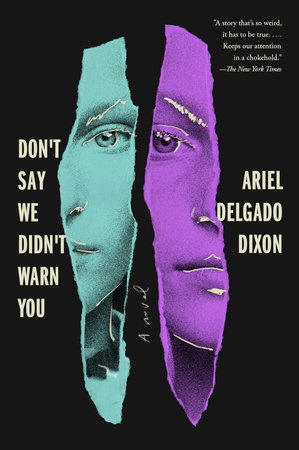

Don't Say We Didn't Warn You

1

My sister always had fixations.

A certain star celebrity, a certain song or food. Anything consumable. She would go at it full tilt for a week or year, however long it took to bleed dry all mystery. She said things that made my mother and I look past her and at each other. Once, driving home from a tearjerker, Fawn mused aloud from the backseat. She couldn’t understand why everyone went on and on after someone died. She was staring out the window, holding her thumb up to the moon. Didn’t they get tired of acting like they were sad? When were you allowed to forget?

It was 2003, and everyone was obsessed with suspicious packages. When the first human appendage appeared—an elbow, somebody’s elbow—I was almost touched. I could hardly believe something so glamorous could happen to us, here in our town.

A postwoman found the limb stuffed inside a duffel bag after nearly running it over on her route. From the raised interstate that cut through Deerie, some culprit had flung away a host of body parts while zooming upstate or down, someone who clearly had no idea there was a rotting hamlet beneath the overpass. The easy off-ramp into town had not yet been built, and the world below appeared as coarse, uninhabited woodland, the scant lights of remaining houses no more than reflections in the window glass. Probably, it seemed like an excellent place for body parts to be tossed, if that was the sort of thing you were trying to do. When the second body part appeared, it came for us. As was her way, Fawn took to it and would not let go.

It began with the dog. He was given to us as a bribe by an ex-boyfriend our mother spurned, and though it was not the first ex to take the tack of wooing her through her children, this bait was extravagant. Fawn claimed him, and I didn’t argue. He came with the name Peanut Butter.

Fawn and Peanut Butter went out for a walk together one morning, the dog nosing around the usual detritus swamped under the highway, when he locked on to one duct-taped bundle. Some sixth sense must have made Fawn think twice. She brought it home under her arm, took the parcel into her room, and shut the door behind her. It might have remained her secret to do with as she pleased, but because our mother was in New York, as she often was, I was left in charge. On this authority, I stormed into Fawn’s room to complain about one thing or another and found her sitting straight-backed at the end of her bed in deep concentration. Her dresser had been cleared but for her prized puppy figurines, and the bundle had been set there, a desk lamp shining over it like an incubator. It was as if she were waiting for it to hatch.

Naturally, and out of earshot, I called my best friend, Zeke, and told him to come right over. I liked my odds when it was two against one.

While I waited for his arrival, I allowed Fawn to expound on her new mystery item and asked a dozen follow-up questions meant to lull her into a state of compliance. She gazed at the taut sheen of plastic.

“What should we do with it?” she asked. The bundle looked complete, like a small wet boulder. “What could it be? What are you?”

The utility door at the street level heaved open. Zeke always took the stairs up to the loft two at a time in a swift, sneakered bound. Fawn swung around and I held my hands up.

“Just wait,” I said. “Okay? Don’t get all crazy. Don’t—”

Zeke banged at the door, and in the time it took me to flick open the lock, Fawn had wedged a chair under the knob of her door. I could hear her pacing, cursing her error in judgment. She shouted through her barricade that I was a traitor, a liar, that she was going to call our mother.

“Does she have a phone in there?” Zeke asked. He had ridden over on his bike, and the heat had glazed him pink, ears and all.

“You don’t have a phone in there,” I shouted back to Fawn.

“You can’t take it,” she said. “It’s mine.”

“Could be drugs,” Zeke said. “Maybe it’s a big brick of drugs.”

“It is not drugs,” I said.

I had anticipated an escalation such as this. For a while, Zeke and I puttered around the kitchen, made snacks with dramatic flourishes, anything to drum up noise and convince Fawn it was safe to emerge. The moment she peeked out, I strong-armed my way in with Zeke on my heels. He snatched the duct-taped bundle from her dresser and tossed it into the air like a baseball to test its heft. It was almost too easy.

Zeke held the package up to Peanut Butter, who had been sequestered in Fawn’s room and was now wagging around our feet, grateful for guests. “What do you smell, boy?”

“Don’t talk to him,” Fawn said. “He doesn’t like strangers. He bites.”

“Zeke is not a stranger,” I said. “Zeke is Zeke.”

The dog licked the package and drooled.

“Maybe it’s a head,” Fawn suggested. “There was a chicken that lived without a head for a whole year. They fed him milk down his neck-hole, but he choked on a corn kernel and died.”

“Congratulations,” I said. “You are disgusting.”

I knew Fawn was looking for an angle in, to shift the situation in her favor. She plucked at soft splinters in the doorframe. “No one listens to me, but I was the one who found it.”

Fresh in our minds were the news reports of the forsaken elbow. I remember the reporter from the local station, the shape of her mouth, coral lipstick, how titillated she was by her first big break. Still, dismemberment was always in our midst. Objects were tossed off the highway in a steady and unremarkable hail. Out of the blue, tricycles rained down, split bags of fetid trash, shipping pallets, smashed bumpers, suitcases, couch cushions, roof tile. Once, a whole toilet. Another time, a bass drum. Wigs were surprisingly common. There was even the sawed-off shotgun Zeke’s brother had supposedly found the summer before. He said he hid it in the woods. He would never say where. Zeke and I agreed. It was like living at the bottom of a landfill. Fawn’s precious bundle was just more junk.

If I doubted this, I was bolstered always by Zeke’s confidence. I trusted him to have answers. He was on his way to becoming an Eagle Scout. He was CPR-certified. I wanted desperately to be in love with him and it was not for lack of trying. It would check a certain box I’d never again have to worry over. That day, he was wearing pre-distressed cargo shorts and a hideous striped polo almost certainly shopped off the mannequin, courtesy of his mother, sunset beach forever stitched across his chest. He liked to dress how he thought Californians dressed. Fawn was still limping through the beginnings of junior high with her baby face, friendless and strange, but Zeke and I were almost free. It was the summer before our senior year.

Behind our huddle, a shatter of glass.

Fawn was standing over a pile of fresh shards. She took one of her puppy figurines in her fist and held it high above her head. “Don’t make me do it again.”

The bundle was in Zeke’s hands. I could see his fingers itching.

“Don’t,” I told him. “She’s showing off.”

“Okay, then,” Fawn said, and smashed her favorite dachshund to the floor. “How about now?”

“You’re just breaking your own stuff,” I said.

“Just give it to her,” Zeke said. “It’s trash. Who cares?”

“I care.” I shot him a look and he bowed his head. It was one-on-one again.

Fawn selected another puppy from her collection and this time pitched a Doberman at the wall behind us. The glass head of the dog skidded across the hardwood. Peanut Butter barked and retreated promptly to Fawn’s closet. He curled himself over her pile of shoes and buried his nose in a moccasin.

I should’ve known Zeke would get queasy over broken things.

“You two figure it out,” he said, and chucked the bundle at Fawn’s feet in surrender. We both lunged for it, but my sister was ready. As soon as her fingers closed around the parcel, she broke into a sprint toward the bathroom, the only other door in our loft with a working lock.

“This is your fault,” I said to Zeke.

“She was aiming for your head.”

“So what? She missed.”

With Peanut Butter trailing behind, we crunched over glass to the bathroom door and waited with ears pressed close as Fawn struggled and grunted against the bundle’s lump weight. Plastic squealed open. She released a sharp breath. All went quiet.

Zeke and I looked at each other and shrugged.

“Fawn,” Zeke said carefully, as if talking down a man on a ledge. “Fawn, listen to me. We should take it to the police. It could be dangerous, okay? Maybe somebody could be looking for it.” He tried the knob. “It could be anthrax.”

“You are so obsessed with anthrax,” I said.

The lock twitched and Peanut Butter reared toward the opening. Zeke snatched his collar and told him to sit, but Peanut Butter didn’t know any commands.

Fawn’s eye appeared in the gap. “You can come in,” she said. “Leave the dog.”