Excerpt

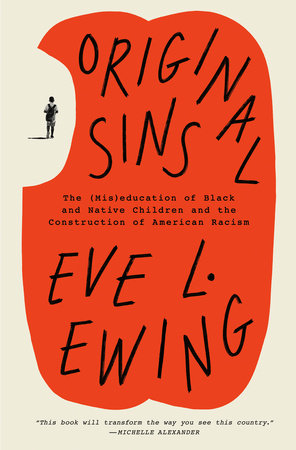

Original Sins

Chapter 1Jefferson’s GhostHow does it feel to be a problem?

W. E. B. Du Bois famously posed this haunting question in 1903, in his classic work

The Souls of Black Folk. I think of it often, especially whenever I encounter one particular line from Thomas Jefferson’s

Notes on the State of Virginia: “Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry.”

It’s stinging in its candor. It strikes me every time, sending me spinning through my own vignettes of the Black poets who set a course for my thriving. In eighth grade, my class took a three-day trip to Washington, D.C., my first time traveling without my family. We visited Monticello. No one brought up the poetry line. I would go through elementary school, high school, college, and my first master’s degree, and no one would ever bring it up. Parts of Jefferson’s legacy were omnipresent in my experience of schooling, and other parts were completely absent.

Before we dive into the three pillars of racism that I described in the introduction, I want to spend some time thinking about Jefferson as a titanic figure in American culture and the impact of his legacy on how we think about racial hierarchy in the United States; we’ll then talk about how this vision has shaped the purposes of schooling along racial lines.

There’s nothing coincidental about how Jefferson does and does not show up in schools and in curricula, or the fact that roughly half of U.S. states have schools named “Thomas Jefferson” (seventy-one total, more than schools named “Abraham Lincoln”). Jefferson’s beliefs about Black and Native people, and the ways he enacted those beliefs as a leader of singular magnitude, laid a cornerstone for the edifice of American racial hierarchy and the contours of American schooling in a distinct way. In the era of Jefferson, Black and Native peoples on Turtle Island posed a mighty problem for the shapers of the new republic. They were an existential threat. And in his writings, Jefferson aimed to tackle that threat through rhetorical moves that would frame the nation and its schools for years to come.

Those who celebrate Jefferson have struggled to reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable ideas that he put forth into the world: On the one hand, he is viewed as the esteemed father of the Declaration of Independence, the champion of the

Bill of Rights and the liberties we hold dear. On the other hand, he held enslaved people as property, and his ideas and policies were crucial in establishing the dogma of Black and Native inferiority. For many people in the United States, faced with the contradiction of Jefferson as a paragon of rational thought who also believed in the inhumanity of Black and Native peoples, Jefferson the erudite intellectual has seemingly won out. In our collective consciousness, the ways Jefferson grievously harmed Black and Native people don’t really matter—he still gets to be the “Sage of Monticello,” representing the zenith of gentlemanly intellect, statesmanship, creativity, and genteel society.

The pedestal of the U.S. presidency is widely understood to represent leadership, moral fortitude, and strength of will. That’s why people love to tell kids they could grow up to be president someday if they work hard enough. But even among presidents, Thomas Jefferson is considered exceptional for his intelligence. In 2006, Dean Keith Simonton, distinguished professor of psychology at UC Davis, published a peer-reviewed journal article purporting to determine the IQ of forty-two American presidents. Simonton declared Jefferson to be the second-most intelligent president, after John Quincy Adams. At a 1962 dinner honoring Nobel Prize winners, John F. Kennedy quipped, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone. Someone once said that Thomas Jefferson was a gentleman of thirty-two who could calculate an eclipse, survey an estate, tie an artery, plan an edifice, try a cause, break a horse, and dance the minuet.”

Jefferson retains a powerful image in the American consciousness, still lauded not only as the progenitor of our democracy but also as an emblem of intellectual excellence. However, two of Jefferson’s key interventions in our country laid the groundwork for anti-Black and anti-Native ways of viewing the world, both inside schools and beyond their corridors.

Notes on the State of Virginia is the only full-length book Jefferson ever authored. In a definitive edited version of the text, historian William Peden called it the “best single statement of Jefferson’s principles, the best reflection of his wide-ranging tastes and talents. It is, in short, an American classic,” “unique in American literary history,” and “probably the most important scientific and political book written by an American before 1785.” While the

Declaration of Independence is certainly the document for which Jefferson is best known, the

Notes were his magnum opus. The text is massive in scope, with twenty-three chapters addressing topics vast in their scale and variety. Jefferson wrote of Virginia’s waterways, its mountain ranges, its militias, its legal system, its fiscal system of income and expenses.

And he wrote of its people.

Historian Arica L. Coleman has posited that the

Notes “may well contain the most disparaging remarks regarding people of African descent ever written.” When I first read these words, I was startled, thinking immediately of all the hateful and vulgar words I have seen deployed against Black people. The more I thought about it, though, the more I had to concede that Coleman may be right. Jefferson’s writings are cloaked in civility and the artful turn of phrase; the aptitude for language that has made him a beloved cultural figure obscures the true violence of what he is saying. Jefferson described Black people’s faces as having an “eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immovable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race.”

He continues:

They secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour. This greater degree of transpiration renders them more tolerant of heat, and less so of cold, than the whites . . . They seem to require less sleep. A black after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning. They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But this may perhaps proceed from a want of fore-thought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present. When present, they do not go through it with more coolness or steadiness than the whites. They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection. To this must be ascribed their disposition to sleep when abstracted from their diversions, and unemployed in labour. An animal whose body is at rest, and who does not reflect, must be disposed to sleep of course. Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.

Such ideas would be hurtful enough if they were merely bigoted perspectives coming from an idly opining individual. But the

Notes represent something on a much grander scale. Jefferson was a son of the Enlightenment, a period characterized by efforts to systematically describe the order of the observable world. The work reflected his character as someone prone to obsessive enumeration, botanical experiments, meteorological observations, and dutiful record keeping. He viewed naming, numbering, sorting, and categorizing as natural strengths to which he was called in life.

Notes on the State of Virginia was not only a treatise espousing Jefferson’s political opinions. It was his attempt to organize the world.

In the

Notes, Jefferson chastises himself and his peers for the fact that “though for a century and a half we have had under our eyes the races of black and of red men, they have never yet been viewed by us as subjects of natural history.” He argues that such study is imperative. Shortly thereafter, he introduces his plan for a system of education to best serve the nation: Every county in Virginia should be divided into school districts. Each year, an expert would choose a brilliant boy whose parents were poor and send him forward for further schooling, to be paid for collectively. “By this means twenty of the best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish annually,” Jefferson explained.