Excerpt

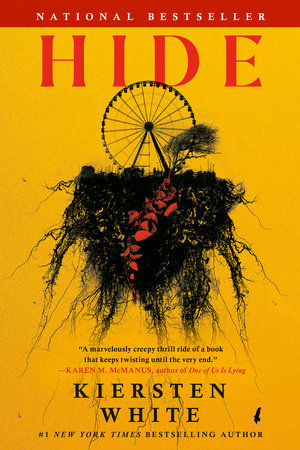

Hide

The Amazement Park opened in 1953.

get lost in the fun! posters advertised, and it was true: Crowds surged through the gates in the morning and didn’t stumble out again until the sun had set, and spotlights at the exit guided them free. The maps were useless, the You Are Here guides impossible to find. It was a park designed to swallow. Trees loomed over lush grounds. Signature topiary lined every walled and wandering path, adding to the sense of wonder. Roller coasters, swings, carousels, games, houses of love and fun and terror—though the house at the very center was always closed for refurbishment.

The park was open from mid-May until early September. whites only was on signs in the early years, heavily implied when such a thing became harder to officially declare. And, for one week every seven years, it was free. The gates would swing wide, and the summer migrant workers and distant relatives of the wealthy townsfolk, normally too poor to enjoy something designed purely for escape, would wander in, wide-eyed. There were no ticket sales, no attendance numbers, just a joyfully packed park.

In 1974, during the free week, a prominent businessman from upstate decided to visit. He hadn’t been invited, but he was considering investing since a cousin-of-a-cousin owned the park. He wanted to see the attractions for himself first, though. He brought along his wife and two children and made it a holiday.

Their little girl, five, was never seen again.

One of the migrant workers was arrested for her murder, but the negative publicity left a stain that didn’t wash out. So the Amazement Park closed its gates.

Eventually, the rumors died. The plants grew. Nature slowly co-opted the buildings, the rides, the roller coasters. What didn’t crumble rusted, and what didn’t rust leaned, and what didn’t lean sagged under the weight of ivy and neglect.

Somewhere, very close to the center—the house that was always closed, where few ever even got, owing to the odd layout of the park—a shoe had caught on the low branches of a topiary. Unchecked, the verdant beast slowly grew higher and higher until the shoe was eye level.

It was patent leather, dulled and cracked with weather and time. The perfect size for a five-year-old foot.

It takes money to make money, her dad used to say.

He also once said Come out, come out, wherever you are, dragging the knife along the wall as music to accompany the dying gasps of her sister. Mack might have imagined the gasps, though. Who could say.

She couldn’t, and even if she could, she wouldn’t.

She’s not saying anything right now, either, sitting across from the manager. The meeting was mandatory, a “shelter requirement,” though she’s been here several months now and this is the first one.

“Come on, Mackenzie. Help me help you.” The woman’s smile is painted on like her cheekbones and eyebrows, and just as artfully. Her expression doesn’t shift at all in the face of Mack’s silence. It’s impressive. Does she do stamina reps in the quiet dark of her bedroom, lifting the corners of her lips over and over, careful not to disrupt her eyes?

The manager clasps her hands together, fingernails painted dark red. “I’ll be honest with you. Things are going to change around here. I believe that we can help only those willing to help themselves. These shelters have stagnated—no hope, no progress. How can we live in a society without progress?”

The voice is animated, but the eyes remain untouched by the sentiments or the smile. Expressionless. Like they’re hidden behind something. Mack feels an odd affinity for this woman, alongside an instinctive wariness. But she disagrees. The point of a shelter isn’t progress. It’s shelter.

“I’ve looked at your file.” The woman gestures to a blank manila folder on the desk. Mack suspects it’s empty. She hopes it is. “It’s bad luck you’re here. I understand. No social safety net to fall back on. A few months without a job, without rent, and it’s hard to dig yourself out. You need to move on with your life. Contribute to humanity. All you need is a little good luck first.”

“Donation bins could use tampons more than luck.” Mack’s voice is soft and dry with disuse.

The woman cracks, something triumphant behind her eyes. Mack shouldn’t have spoken. The woman holds up an envelope. “It just so happens, some luck has come in the mail. Whether it’s good is really up to you. Right now, it’s an opportunity. And I think you’re perfect for it.”

Mack has never been perfect for anything in her life. Perfect feels like a foreign word, stiff and uncomfortable. But maybe it’s a job. A little money to get presentable and she’ll have an actual chance. As long as they don’t pry. As long as they don’t look too closely. She could make it work.

She takes the sheet of paper the woman slides across the desk. It’s thick. It feels expensive. Mack is suddenly aware of her hands—her bitten fingernails, her shiny burned palms, her ragged cuticles. If she sets down the paper, will she leave a smudge? It’s hard to be embarrassed at this point in her life, but the idea wriggles beneath her skin.

She’s so worried about leaving a fingerprint—one that will somehow count against her in this imaginary job interview—that it takes her several seconds to process what she’s reading.

“Is this a joke?” she whispers.

The woman’s smile doesn’t budge. “I know it sounds like one. But I assure you it’s legitimate.”

“Who told you?”

Finally, the woman’s cheeks relax, and her eyebrows draw close. “What do you mean? Who told me what? That it’s legitimate?”

About me, Mack thinks. Who told you about me? But the woman’s confusion can’t be feigned. Can it? If she can paint on a face, can she paint on emotions, too? Mack drops the letter. There are no fingerprints. But the words have left smudges across her mind.

“Why are you giving this to me?” Mack knows how lost she sounds, how scared, but she can’t help it. “Why me?”

The woman laughs, a single dismissive burst. “I know it seems silly. The Olly Olly Oxen Free Hide-and-Seek Tournament. It’s a children’s game, for god’s sake. But it’s a chance to win fifty thousand dollars, Mackenzie. You could use that to actually move up in the world. You’re young. You’re intelligent. You’re not a thief, you’re not an addict. You shouldn’t be here.”

No one should be here. They all still are.

The woman leans forward intently. “It’s run by an athletic company, Ox Extreme Sports. I can put in a good word and get you registered. There’s no guarantee you’d win, but—I think you have a shot. It’s more about endurance than anything else. Besides, you strike me as someone who’s good at hiding.”

Mack’s chair scrapes back, jarring them both. But Mack can’t be in this room, can’t think, not while she’s being looked at. Not while she’s being seen. The woman doesn’t know about Mack’s history, and still, somehow she knows.

“Can I think about it,” Mack states. It’s not a question.

“Of course. But let me know by tomorrow. If you don’t want the spot, I’m sure someone else will. It’s a lot of money, Mackenzie. For a silly game!” The woman laughs again. “I’d enter it myself, but I can’t go more than twenty minutes without needing to pee.” She waits for Mack to laugh, too.

She’s still waiting as Mack slides out through the door, not even a whisper in her wake.

Everything about the shelter is designed to remind them that nothing is theirs. There are no lockers. No alcoves. No closets. No bedrooms. In a featureless box of a space, the ceiling looming so far overhead a bird lives in the beams, there are cots. Each has the same stiff white sheets and scratchy blankets. The area beneath the cots is to be kept clear at all times. They are not allowed to use the same cot more than two nights in a row. Anything not cleared by nine a.m. will be confiscated and thrown out, so they can’t even leave their meager possessions on the cot that is not theirs.

When the cots are all filled, Mack is as good as hidden. She’s small. She’s quiet. But now she feels as though a spotlight has been trained on her. Everyone else has already cleared out for the day. Some will go to whatever work they’ve found. Several will sit outside on the sidewalk until they’re allowed back in at four p.m. The rest, who knows. Mack doesn’t ask. Mack doesn’t tell. Because she goes somewhere she doesn’t want any of them to know about, either.

Hidden behind a half wall, choked with the scent of burning dust, an old water heater sizzles and rages. She has permanent shiny burns on her hands from where she scales the water heater, wedges herself between walls, and shimmies up.