Excerpt

Lucky Me

1

R&J Confectionary My story begins in 1978, with a young woman walking toward the corner of 125th Street and Edmonton Avenue. She’s recently arrived in Cleveland from St. Louis, looking for a fresh start at age twenty-four. A beauty with chocolate skin, a body shaped like a Coke bottle, a walk that’s impossible to ignore, and a taste for the kind of street life her new city is known for. Her name is Minerva Norine Martin.

There’s a store on the corner, and Minerva opens the door. She loves to dress, so she’s probably wearing a skirt and some pumps, a couple rings on her fingers, with her trademark dyed streak of blond in the front of her straightened hair. The small, narrow store is clean and well stocked. It has coolers with eggs, milk, cheese, soda, and beer. Shelves with candy, bread, chips, cereal, and baking soda. Cigarettes behind the counter. Some video games, big consoles almost as tall as the coolers, like Defender or Pac-Man. A coin-operated pay phone is attached to the wall.

A man wearing a dress shirt and pleated slacks stands behind the counter. He worked his tail off to get there: Served in the army in Korea, sweated in a factory that made stamping machines, drove a jitney car, installed roofs, took some college courses in business administration, ran numbers, and had all kinds of other side hustles. It took him fifteen years to save up to buy the store’s building for twenty-five thousand dollars cash, which back then was major paper. The man has a natural mind for business, for what people need and how to sell it to them, whether that’s milk on credit or Acapulco Gold weed. Now he’s thirty-three years old and a pillar of the neighborhood as the owner of R&J Confectionary. The J comes from the name of his wife, Justine. The R stands for Richard--Richard Paul.

Richard takes stock of Minerva. He knows everybody in the neighborhood and everybody knows him, but this is something new.

“How you doing, sweetheart,” Richard says. “How can I help you?”

“I’m fine, thank you. Y’all got Newports?”

“For sure, baby. I never seen you around here before, where you from?”

“St. Louis. We just moved in down the street.”

“Welcome to the neighborhood. I’m here 24/7/365 for the most part, baby. We got an after-hours thing upstairs starting at ten, bring whoever you want. Just ask for Rich, you won’t have no problems. So what’s your name?”

Their eyes lock. My future mother answers:

“Peaches.”

That’s what everybody called her: Peaches. Wasn’t much soft or sweet about her, though. My mom was a firecracker, the center of attention in every room, always ready to set the party off. She grew up in St. Louis, the fifth of eleven children born to Mickey and Ruth Martin. In a family that big you had to go for yours, so my mom learned at an early age to be aggressive. If she wanted something and none of her brothers or sisters could legitimately claim it, she’d grab on to it like a pit bull. But she was a giver, too, and loved her family to death. She enjoyed taking care of her younger siblings, so she learned early how to cook amazing meals for them. When she got older, it was nothing for her to whip up a whole Sunday dinner on a random Tuesday. She worked jobs from fast-food restaurants to nursing homes and always had something moving on the side. She sold clothes or shoes that she obtained from different places--don’t leave your winter coat at her house, it might end up in a yard sale that spring. She’d buy a half dozen bottles of liquor, mark them up a couple dollars, and pocket the difference. She’d bake cakes and pies and sell them up and down the street, or cook up a bunch of food, drop it into Styrofoam containers, and roll through the local bar telling people, “C’mere and give me seven dollars for this fish dinner.” Pot roast, cabbage, macaroni and cheese, she could cook it all. When it came to that hustle, that grind to get money? Peaches was about that work.

She was also about those streets.

My mother liked attention. In a family of eleven kids, twelve if you count her extra stepbrother, attention was in short supply. She found it out partying. My mom started popping pills when she was thirteen years old, what they called “blues,” which were like Xanax or Valium. There was a lot of weed around, too. This was the late 1960s into the early ’70s and heroin was starting to hit big, but my mom was scared of needles so she didn’t get into that. Her boyfriend Ralph did, though. They had two children together: my sister Brandie, who was born in 1975, when my mom was twenty years old, and my brother James, who was born in 1977.

Everybody calls my brother Meco (rhymes with “free throw”). After Meco was born, my grandfather got a job at a factory in Cleveland. He moved there, my grandmother followed him soon after, and then they broke up. Things got rough for my mom in St. Louis, with two kids whose father was addicted to heroin, so my mother brought Brandie and Meco to Cleveland, and they moved into my grandmother’s house at 12617 Edmonton Avenue.

That house was half a block from Richard Paul’s store.

Actually, R&J Confectionary was way more than a store. Richard Paul was the type of person who liked to take care of everybody, so R&J was also a credit union, food pantry, taxi stand, community center, and more. Parents knew their kids were safe there buying penny candy and dropping quarters into the Donkey Kong game. You could get some bread and eggs a couple days before your paycheck arrived. This was before cellphones, and guys who got locked up would use their one call from jail to ring the store pay phone and tell my dad to tell their people to bail them out. R&J Confectionary was a neighborhood institution, and Richard Paul was a caretaker of the community.

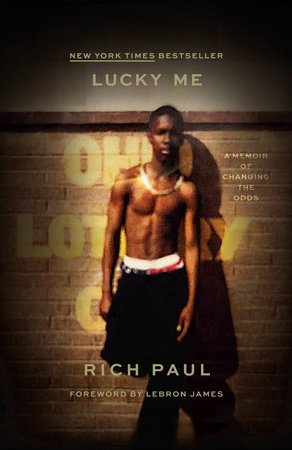

Richard took such good care of Peaches that I was born on December 16, 1980. He insisted that I have his name.

My dad was already married to Justine; they had a daughter, my sister Nicki, and they lived in a house on Ardenall Avenue in East Cleveland. But Richard Paul Sr. was not the type of man to ignore his responsibilities. He was a stand-up guy, and whatever he did, he owned it. He was always the fullest of full-time fathers to me. A few years after I was born, when Brandie and Meco’s father died, Richard assumed the responsibility of raising them, too. They call him Dad to this day.

When I was a baby, Dad got my mom a place on Woodworth, not far from his house. At this time, Cleveland as a city was close to rock bottom. Once upon a time, in the late 1800s, the city was a center of American industry, the place where John D. Rockefeller built his Standard Oil empire back when Euclid Avenue was known as “Millionaires’ Row.” We became a factory town with strong labor unions, plenty of good working-class jobs, and a thriving Black community filled with bars, restaurants, and chitlin circuit clubs--105th Street was our version of the famed 125th in Harlem. But as the city moved through the 1970s, a lot of the machines, steel, and cars we manufactured became obsolete, or could be made cheaper in other countries. Businesses and residents left for the suburbs. Dad used to work in the Addressograph factory, which manufactured devices that stamped addresses on paper, using ink and rubber letters. That was a recipe for bankruptcy. As the jobs dried up, neighborhoods got run-down and houses were abandoned. Legal ways to make money became harder to find. People needed to survive, so crime increased.

All of this happened just in time for the arrival of crack cocaine.

A lot has been said about how crack devastated the Black community, but I’m here to testify that unless you lived through it, you really don’t know. Crack had a destructive power that was unique in the history of narcotics. It was worse than the pills my mom popped, because the high was more intense but shorter in duration. It was worse than heroin, because it hyped you up instead of nodding you off. And crack smokers needed their hit so frequently, the sheer amount of product that was moving flooded the streets with cash, more than the hood had ever seen before. All that money flowing through the neighborhood increased the levels of violence in the city. So in addition to our people getting hooked on this horrific substance during the 1980s, young Black males started killing each other at an unprecedented rate.