Excerpt

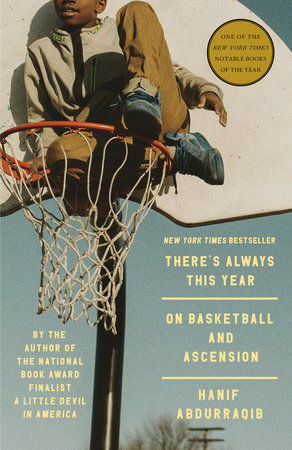

There's Always This Year

5:00 You will surely forgive me if I begin this brief time we have together by talking about our enemies. I say our enemies and know that in the many worlds beyond these pages, we are not beholden to each other in whatever rage we do or do not share, but if you will, please, imagine with me. You are putting your hand into my open palm, and I am resting one free hand atop yours, and I am saying to you that I would like to commiserate, here and now, about our enemies. And you will know, then, that at least for the next few pages, my enemies are your enemies.

But there’s another reality: to talk about our enemies is also to talk about our beloveds. To take a windowless room and paint a single window, through which the width and breadth of affection can be observed. To walk to that window, together, if you will allow it, and say to each other How could anyone cast any ill on this. And we will know then, collectively, that anyone who does is one of our enemies. And so I’ve already led us astray. You will surely forgive me if I promised we would talk about our enemies when what I meant was that I want to begin this brief time we have together by talking about love, and you will surely forgive me if an enemy stumbles their way into the architecture of affection from time to time. It is inevitable, after all. But we know our enemies by how foolishly they trample upon what we know as affection. How quickly they find another language for what they cannot translate as love.

4:25

Our enemies believe the twisting of fingers to be a nefarious act, depending on what hands are doing the twisting and what music is echoing in the background and upon which street the music rattles windows. Yet there is a lexicon that exists within the hands I knew, and still know. One that does not translate to our enemies, and probably for the better. Some by strict code, some by sheer invention, but I know enough to know that the right hand fashioned in the right way is a signifier—an unspoken vocabulary. Let us, together, consider any neighborhood or any collective or any group of people who might otherwise be neglected in the elsewheres they must traverse for survival, be it school or work or the inside of a cage. Let us consider, again, what it means to have a place as reprieve, a people as reprieve, somewhere the survival comes easy. Should there not be a language for that? A signifier not only for who is to be let in but also who absolutely gotta stay the f*** out?

There are a lot of things our enemies get wrong, to be clear. But one thing they most certainly get wrong is the impulse that they should be in on anything, and that which they aren’t in on is the result of some kind of evil. But please believe me and my boys made up handshakes that were just ours, ones where we would slap hands and then make new, shared designs out of our bent fingers, pulled back and punctuated with a snap. We would break them out before parting ways at the bus stop to go to our separate schools, and break them out again upon our return at the end of the day. The series of moves was quick, but still slow enough to linger. Rarely are these motions talked about as the motions of love, and since we are talking about our loves over our enemies, lord knows I will take whatever I can to be in the presence of my people. To have a secret that is just ours, played out through some quiet and invented choreography. A touch between us that lingers just long enough to know we’ve put some work into our love for each other. We’ve made something that no one outside can get through. I do not waste time or language on our enemies, beloveds. But if I ever did, I would tell them that there is a river between what they see and what they know. And they don’t have the heart to cross it.

4:10

And since we know our affections well, we also know the granular differences between their movements—the moment when an existing sweetness is heightened, carried to a holier place, particularly when orchestrated by someone we know that we love. For example:

3:55

The difference between enjoying food and enjoying a meal. I believe there is a sliver of difference between being naked and being bare; I believe that difference also exists between those who enjoy food and those who enjoy a meal. A meal is the whole universe that food exists within—a universe that deserves its own type of ritual and honoring before getting into the containers of it. As a boy, I got into the habit of watching my father eat. At dinner, our table was circular, and on the nights when it was all of us, four kids and two parents, my mother and father would sit in the two chairs on one side of the table. I would sit directly across from them, along the other side. I loved being an audience to my father’s pleasures, a man who did indeed have a deep well of pleasures to pull from, but a man who was also kept from them far too long, for far too many days, working a job he didn’t love but needed. Of the many possible ways to do close readings of pleasure, among my favorite is being a witness to people I love taking great care with rituals some might consider to be quotidian. And my father was a man who enjoyed a meal. Our dinner table was mostly silent, save for the pocket-sized symphony of metal forks or spoons and among them, my father, the lone vocalist, mumbling or moaning through bites weaving in and out of the otherwise mechanical noise with sounds of his present living. But even before a meal, my father would prepare, slowly: blessing the food in Arabic, seasoning it, stretching a napkin wide. There was a point I always loved watching, when he first set upon his plate, deciding exactly what he was going to allow himself to enjoy first. The moment never lasted more than a few seconds, but it was always a delight. To know that even he was at odds with his own patience, wanting to measure his ability to sprint and his ability to savor.

My father is a man who has no hair atop his head. I’ve never seen my father with hair, save for a few old photos from before I was born or shortly after where, even then, his head is covered by a kufi—only revealing that there is hair underneath by some small black sparks of it fighting their way out of the sides or down the back. It is because of one of these photos that I know my father had hair when I was a baby, too young to remember anything tactile about my living. In the photo his head is covered and he is holding me, but there is, unmistakably, hair in this photo. There is no way to tell how abundant it is or isn’t, no way to tell if it was ever robust enough for me to have run a small and curious hand through it while resting in his arms and fighting off sleep.

But in my conscious years, I never knew my father to have hair, which is, in part, why watching him eat was such a singular delight. No matter the level of seasoning that was or wasn’t on his food, small beads of sweat would begin to congregate atop his head. A few small ones at first, and then those small ones would depart, tumbling down his forehead or toward his ears to make way for a newer, more robust set of beads. This process would continue until, every now and then, my father would pull a handkerchief from what seemed like out of the air itself, dabbing his head furiously with one hand while still eating with the other. The sweat, I believed, was a signifier. This is how I knew my father was somewhere beyond. Blown past the doorstep of pleasure and well into a tour of its many-roomed home, an elsewhere that only he could touch. One that required such labor to arrive at, what else but sweat could there be as evidence?

I never saw the old photos of my father with hair until I was in my teenage years. I don’t remember when it was that I realized that the bald black men I loved had hair once. Or that they put in work to keep their heads clean, to stave off whatever remnants of hair might try to fight their way back to the surface. My father and grandfather both had clean heads. And they both had thick, coarse beards that they cared for rigorously. The scent of my father’s beard oil arrived in rooms before he did, lingered long after he left. He approached his beard care with a precision and tenderness—his fingers shuffling through his beard when he spoke or listened intently, a beard comb peeking out of his front pocket at almost all times, hungry to once again tumble through the forest of thick hair, be fed by whatever remnants clung to the teeth on the way down.

Because I came into the world loving men who had no hair on their heads but cared for what hair they did have—bursting from their cheeks, or curved around their upper lips like two beckoning arms—it seemed that this was a kind of sacrifice made in the name of loving well, of having something that a small child could bury their hands in, something closer to the ground those hands might be reaching up from.

If my father worked in the backyard washing his car or hauling some wayward tree branches, his bald mound laid out for the birds to circle around in song, I could see the sunlight find a spot to kick its feet up, right at the crown of his head. I was so young, and so foolish, and knew so little of mirrors. I imagined that if I crawled high enough, on the right day, I could look down from above and see my own face reflected back to me from atop my father’s shining dome. And nothing felt more like love to me than imagining this. A man whose face I hadn’t grown into yet, wielding an immovable mirror which is, always, a sort of promise which, through your staring, might whisper to you Yes, this is what you have now. Yes, the future has its arms open, waiting for you to run.