Excerpt

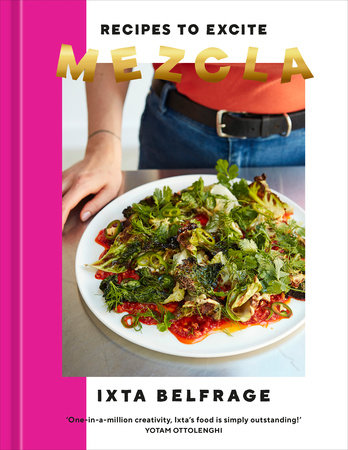

Mezcla

IntroductionThe word

mezcla (not to be confused with the delicious drink mezcal) means “mix,” “mixture,” “blend,” or “fusion” in Spanish. It’s a beautiful word that has meaning in food and cooking, and also in music and art.

Within the context of this book, it’s about mixing flavors and ingredients, but it also goes beyond that. It’s about how my mixed heritage and upbringing have shaped the person that I am and, ultimately, the way that I cook.

There’s inspiration from around the world in these pages, but this book is largely an ode to three incredible countries that taught me to love food: Italy, where I lived as a child; Brazil, where my mother is from; and Mexico, where my paternal grandfather lived. Three countries that I grew up traveling to, eating in, obsessing over—three countries whose cuisines and ingredients have come to overlap in my subconscious over time, leading me to create food that has been described as “quintessentially Ixta.”

So, here’s a little bit about my life so far, and how it’s shaped the way I cook . . .

From Italy, Brazil, and Mexico, with love My story begins halfway up a mountain in Tuscany. When I was young, my father’s job was cultivating relationships with Italian wine producers, and so we moved to Tuscany when I was three.

We lived in the old servant quarters of a beautiful fifteenth-century villa, surrounded by rolling Tuscan hills, vineyards, and olive groves as far as the eye could see. My sister and I spent our days roaming the countryside with our dog, Giacomino, and life was pretty damn good.

I quickly became best friends with a girl I met at school, Giuditta, whose family changed my life by introducing me to the best Tuscan food, which is arguably the best food (along with Mexican and Brazilian food, but we’ll get to that). Giuditta’s uncle was the chef-owner of a restaurant called La Casellina, which served dishes that I came to fall madly in love with. Dishes like chicken liver crostini, tagliatelle with duck ragù, ravioli with crema di rucola, fritto misto of rabbit, zucchini flowers and sage leaves, and so much more. Giuditta’s grandfather, Ferruccio, used to make all the pasta for La Casellina in the laundry room of their family house, so whenever I went over, I would hang out with Ferruccio and watch him make pasta. I’ll always associate the smell of clean laundry with fresh pasta.

I am forever grateful for this beautiful part of the world where I spent my formative childhood years, the only place I feel truly at home. In the summer, the air is heady with the smell of ripe fruit, cypress trees, dust, and grass. The sun shines brighter and time goes faster and slower all at once. The air is thick, dry, and hot but, somehow, so much easier to breathe. I am not Italian, and in the grand scheme of my life so far, I didn’t live there very long, and yet deep in my bones I feel that this mountain in Tuscany, more than anywhere else, is home.

The Brazilian influence comes from my mother, who is from Natal, in the northeast of the country. We visited many times when I was growing up, and I lived in Rio de Janeiro for a year when I was nineteen, one of the best years of my life and the last time I remember having absolutely no worries. I woke up to eat, go to the beach, drink, and party, and slept just so I could do it all over again. It will come as no surprise that what I love most about Brazil is the food. I could write a whole book about my experience of the food in Brazil, but I need to condense my feelings to just a few paragraphs, so I’ll tell you about one of my death row meals (of course, there is more than one).

When we used to visit my mother’s hometown, we would stay near Ponta Negra beach. It was idyllic, peppered with palm trees and punctuated by Morro do Careca, an enormous and majestic sand dune down which people happily plunge all day. The beach was home to a few fish restaurants, and we had a favorite, of course, a rudimentary shack in the sand, the tables of which were close enough to the sea that the water would lap around your bare feet as the tide came in and the meal stretched into the late afternoon. Plastic tables were first loaded with moqueca (seafood stew), pirão (a sort of porridge made by beating hot seafood stock into coarse cassava flour), macaxeira frita (fried yuca chips), and an endless flow of guarana and caipirinhas. Next came whole fish and giant shrimp, pulled fresh from the sea in front of our eyes and grilled next to our table. This was the meal of dreams.

Brazil holds a very special place in my heart, and you’ll see its influence throughout these pages.

My father was born in the US to English parents. He grew up in the Bronx, an avid Yankees fan, during the McCarthy era. When he was fourteen, his father was accused of being a communist (he had been for a time, and still held allegiances) and was deported.

This might seem irrelevant, but the fact that my grandfather was deported from the US led him to settle in Mexico, where he spent twenty-eight years of his life in a beautiful house in Cuernavaca, just outside Mexico City. Along with his wife, Mary, he ran this as a halfway house for political refugees, a halfway house where my mother and her family would find safety in ’66, having fled from the Brazilian right-wing military regime.

From the garden of this house in Cuernavaca you can see the volcano Ixtaccíhuatl (sometimes spelled “Iztaccíhuatl”), which is my namesake and explains my affinity for volcanoes. My parents first met in my grandfather’s garden in Cuernavaca (although they didn’t end up together until decades later) and that’s how I ended up with my name, although luckily they dropped the “ccíhuatl” and just called me Ixta.

Because of all this, Mexico was also a huge part of my upbringing. I have never lived in Mexico (a fact I will one day correct), nor do I have Mexican blood, but it is very close to my heart. The country and its food feel like a part of my identity. I felt this connection before I ever went there, most likely because of my Mexican name, but also undoubtedly because of the significance of the country as a place of political refuge for both sides of my family.

When we visited my grandparents’ house, there was nowhere I wanted to be more than the kitchen. It was quintessentially Mexican: decorated with tiles, terracotta, and concrete in shades of deserts and sunsets. Their cooks were Gumer and Maria Concha, two short ladies with long gray hair, the kindest eyes, and the widest smiles. By the time I met them, they had been cooking for my grandparents for twenty years. I hung at their elbows, marveling at their speed and skill in stuffing and frying my favorite chiles rellenos (stuffed peppers), rolling corn tortillas, and pounding chiles and spices for moles and salsas in a huge molcajete (mortar and pestle) made from volcanic rock. Made from a little piece of Ixtaccíhuatl, I always liked to think.

Growing up, I always found myself in the kitchen. Watching. Learning. Little did I know that I was soaking up food traditions like a sponge, because when I started cooking at a young age, having never been properly taught, it all just came naturally, like muscle memory from a past life.