Excerpt

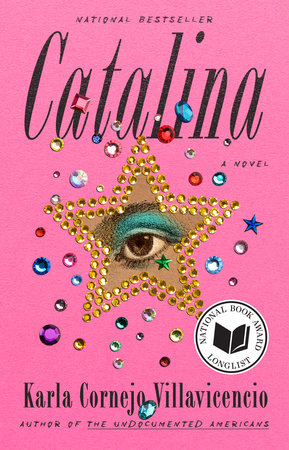

Catalina

Part One

SummerIn the summer of 2010, the year Instagram launched, there was a cricket invasion in Queens. Something to do with global warming and, if you believed my grandfather, yet another sign that America was lagging behind Cuba in scientific advances. He was not a communist, he just had a bit of a thing for Fidel. Dozens of crickets were under the floors and in the walls of our apartment. The landlord sent an exterminator, but it had little effect on their fornication. The sound was intolerably loud. My grandfather said that back in Ecuador, summer nights in Esmeraldas were so loud, it sounded like, well, what it was—a beach and a jungle. I had not been to Esmeraldas, where he spent every summer as a child. Like him, I was undocumented, so I could not go to Esmeraldas, probably ever. I would probably never see the Amazon, and thus I would never really know a summer night. He would always have that over me. He knew in his flesh what I could only read about and I read a lot.

As a kid, I read for escape, and nothing could be further from watching a cockroach lay dozens of tiny eggs on the kitchen sink than Jay Gatsby and his amorous preoccupations. I could relate to some of it—his immigrant hunger and interminable longing; I’d been to Long Island—but the lives of Nick and Daisy and Jordan were incomprehensible to me. I didn’t understand what they wanted or why they wanted what they wanted. Their main problem seemed to be boredom. The cannon was white noise, and it was perfect.

I spent that summer, which was the summer before my senior year at Harvard, interning at America’s third-most-prestigious literary magazine. Does that sound like a setup for a romantic comedy? I thought so, too. My expectations were high. During my commute, every single morning, on the L train between Bushwick and Manhattan, I just had a feeling Woody Allen was going to discover me. Rosario Dawson had been discovered on her stoop on the Lower East Side as a teenager. Charlize Theron was discovered at a bank. Toni Braxton was discovered at a gas station. I needed to be discovered because I wanted to get out of where I was, and according to Jay Gatsby and Joseph Kennedy, Sr., and Theodore Dreiser and Jay-Z, I could do it by becoming a star. It was a long shot but so was everything. If I didn’t commit to Catalina, Catalina, Catalina, I would die of tuberculosis two decades ago, another uninsured girl at Bellevue known only by her wristband. If at any point I stopped believing, the spell would break. To be clear, it was Woody Allen who would discover me because he was a local. Almodóvar lives in Spain, and Sofia Coppola might find me too busty. Plus, if there was someone looking for muses on the train and if that muse was going to be a very young girl, for the verisimilitude of the thought exercise, it had to be Woody Allen.

Four years at Harvard had been presented to me like a trip to Disney World to a terminally ill child and the end was coming. I could not be legally employed after graduation. Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t legally able to work that summer, either, but my lack of papers did not matter because unpaid internships did not pay and I only applied to unpaid internships. Employers argued it was not “work.” Usually, the only people who could afford to do that sort of thing—move to New York for at least three months and live there without making an income—came from some kind of money, which kept that world small. But so long as I was enrolled in school and lived with my grandparents, I could do as many unpaid internships in media as I wanted. They could be like Pokémon cards.

I loved newspapers and magazines as a child. I was the perfect age for Highlights for Children when I came to America, and within a couple of years I graduated to Reader’s Digest and then a couple of years after that I moved on to Time. By high school I was stealing old copies of The New Yorker from the school library. I had favorite writers (Alma Guillermoprieto for The New York Review of Books) and favorite publications (the Oxford American). I had opinions about paywalls and subscription models and the sustainability of relying on billionaire benefactors. But my love for American periodicals was not why I wanted to be a writer.

If you think about it, I never really even had a chance. I was named after the old Manuel Vallejo song “La Catalina,” so I’ve known the tacky-sweet suet of self-protagonism since I was a little baby bird. I grew up with a soft spot for songs named after girls. I liked “Roxanne” by the Police, “Allison” by the Pixies, “Arabella” by the Arctic Monkeys, “Julia” by the Beatles, “Michelle” by the Beatles, “Lovely Rita” by the Beatles. There’s a picture I saw on Tumblr of Bianca Jagger backstage at a Rolling Stones show. It’s actually a picture of her foot in a white platform sandal; tucked into one of the straps is a backstage pass with her name on it. Whatever that was—I wanted to be that. Not Bianca Jagger. Not Mick Jagger. I wanted to be the photograph. I wanted to be Art. I knew it was only a matter of time before a boy in a band wrote a song about me, but that would require patience and I suspected the song would not be very good. Once again, I would have to rely on my own scruples to make things happen. I would have to become a writer myself.

I was on Tumblr since the beginning and eventually started writing myself, a blog that developed a small but devoted following of readers. I mostly wrote about music and made annotated breakup playlists for celebrity couples on the rocks, like Meg White and Jack White, and J.Lo and Ben Affleck. After that, I wanted to move up in the world, to blogs attached to iconic institutions like Interview magazine and The Atlantic. I pitched them coldly using emails I’d guessed from mastheads and did not lie about my age but did not volunteer it. I started covering shows, which gave me entry into twenty-one-plus venues because my name was on the press list. If you think I did not gallop like a newborn pony to the bouncer to say I should be on the guest list with the intended affect of a young Katharine Hepburn, you don’t know Catalina Ituralde!

My grandparents supported my efforts. They had their suspicion of worldly gatherings and entertainments but I told them, had shown them in my heavily highlighted copy of The Fiske Guide to Getting into the Right College, that I needed to have extracurricular activities to impress admissions committees. That’s all it took. My grandma helped me pick out what to wear to shows, and if I got out after midnight, my grandfather picked me up right outside the venue. It was all very wholesome. The three of us were a family that did things together.

The summer of the cricket invasion my grandparents both walked me to the Myrtle Avenue train station every morning. From there, I took the train to my internship in Greenwich Village, and my grandfather took a different train to his job at a construction site in Midtown. My grandmother speed-walked back home, determined to miss as little of Live with Regis and Kelly as possible.

I have long since forgotten the names of the other summer interns except for Camilo Oliveres. We met when the internship director ushered us into the kitchen on the first day to explain that she had an honorary title to split between us. It was named after a slain El Diario editor who was killed by a Colombian crime boss at a restaurant in Jackson Heights. There was no money involved, no special duties or honors or responsibilities. The only stipulation was that the recipient be Latine.

“I’ll step aside if that’s okay,” Camilo said. He spoke English with a Mexico City accent. I wondered if he could place mine. I blushed.

“Catalina, how about you?” the internship director asked. “Can we give this to you?”

“That sounds great, thanks,” I said.

Technically, only I was Latine. Camilo, I would learn, was Latin American. His parents were psychoanalysts from Spain who fled Franco’s persecution of leftist dissidents and resettled in Mexico, where they had him. He looked like he could be anything but he was Spaniard by blood and Mexican by birth. This allowed him to take certain liberties with me, for example, to speak to me in Spanish. When we walked back to the intern pen—that’s what it was called, the intern pen—Camilo motioned for me to walk before him and said, a bit songsongy, licenciada. It was a layered inside joke, requiring a lot of assumptions he was not wrong about, among them, that I was not to be taken seriously.

The magazine’s music editor had been recently fired, so I was assigned instead to Jim Young, the literary editor. Jim was partial to young women, not in a lascivious way necessarily—it was a matter of preserving the delicate balance of his ego. My job consisted of reading all the unsolicited short-story submissions the magazine received and passing any promising ones to Jim—rarely, very rarely. The magazine got a lot of letters from prisoners, and I always sent them copies of the magazine. Whenever I asked Jim to do something menial, like sign a contract or respond to an agent’s query, I suspected I was taking editing time away from his writers, famously difficult men who wrote tens of thousands of words about being sad and horny, writers who couldn’t spare the editing sessions.

When Jim passed by the intern pen, he’d greet me by asking, “Found any diamonds in the rough?”

“No,” I said each time. “Not yet.”