Excerpt

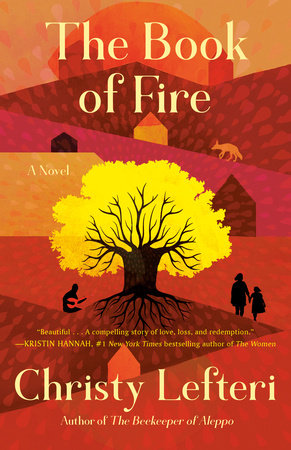

The Book of Fire

1 This morning, I met the man who started the fire.

He did something terrible, but then, so did I.

I left him.

I left him, and now he may be dead. I can see him clearly, exactly as he was this morning, sitting beneath the ancient tree, his eyes blue as a summer sky.

The man I left to die was never the type to come to the Kafeneon for a Greek coffee and bougatsa. He kept himself to himself, so I’d only ever greet him in passing, usually as he walked from his massive villa down to the sea and I went up to the top of the mountain with Rosalie, our greyhound. Even then, he hardly made any effort. He smiled with distracted eyes and didn’t bother to say a word.

He was a property developer who had moved here from the city. None of us in the village liked him that much, even before the fire. And we have been justified, really.

Was it Aristotle who said that man is a political animal? Not that we are all born to take an active interest in party politics, but it is in our nature to live in a

polis, a community. So, as a joke, we called this guy Mr. Monk, because he seemed to live like the monks in the monastery in Olympia, except that he was rich and very well dressed. I can’t even remember his real name.

In mythology, Zeus gave Hermes two gifts for humankind: shame and justice. When Hermes asked if he should distribute these gifts to some and not others, Zeus said no. Every single person should possess these gifts, so that they could all learn to live together. Even in the distant past, people understood the importance of community, so they infused their stories with these morals. Zeus even said to Hermes that if someone was without a sense of shame or justice when doing wrong, they should be put to death by their community.

But that was centuries ago, and we’ve come a long way since then, right?

Mr. Monk stole the world. At least, the part of the world that I call my own. He obliterated beautiful mornings.

For many years, I was in the habit of waking early as the sun rose over the firs. I’d open the window, summer or winter, to take in their smell, to watch them stand so tall and silent. In the winter, they appeared like ghosts through the fog, and in the spring, they were green and fresh and bright, and heather bloomed by the thousands in their shadows. In the summer, light fell upon them so peacefully. At such an early hour, everything was soft and harmless. I used to make a cup of tea and stand for a while, looking out of the window. My husband was nearly always still asleep. He was the type to work into the night. Only the birds could be heard. Nothing else. Autumn was my favorite season, the way the trees looked like flames upon the hill and the air was crisp. I loved sensing the coming cold, the whisper of it on the wind.

He took all this, the man who started the fire.

The point is that Mr. Monk lacked humanity.

To live our lives with a sense of justice in our hearts would inevitably mean seeking fairness in the way people are treated by others—or indeed by us. It’s not that Mr. Monk hasn’t acknowledged what he’s done; it’s just that he has been trying to get away with it. As for shame—shame is a tradition in Greece! But perhaps Mr. Monk would not feel bad for doing wrong had he not been caught in the act. My question is, does he feel guilt? Is he suffering for what he has done to us all?

Then, there’s this: yesterday, ash rained down from the sky. My daughter and I both saw it. It is January now, five months since the fire. We were standing at the window that faces the forest. All you can see from that window are the endless skeletons of pines, some taller, others merely stumps. Over this fell the ash.

“It looks like snowflakes,” I said to Chara, who was standing by my shoulder; I could hear her breathing, but she said nothing. My lovely, sweet Chara, too old for her age. Her name means

joy. Chara with a silent C. She loved it once, loved how its happiness was a secret kept from all who didn’t know its origin, like a secret summer garden. There are many secret places in her mind, even at such a young age, and some are not full of light or color or ancient trees: some are dark; some are empty; they are stark.

The ash began to settle on the fig tree in the garden, the only living tree, where my husband, Tasso, sat quietly, staring out toward the slope of the mountain, his bandaged hands resting on his lap, palms facing up, as if he were waiting for something to fall from the sky. I saw him shudder from the cold, but he did not move to come in; instead, he inclined his head and looked up. Rosalie sat by his feet, as always. His protector.

“The ash is settling,” I said, as if Chara couldn’t see it herself.

“It’s snow, Mamma,” she huffed and walked away.

I heard her footsteps along the old wooden floor, then silence.

Was it really snow? I looked more closely, strained my eyes. Indeed, it was. It glimmered, sparkled beneath the midday light. It brought new life. Of course, ash would not be falling from above months after the fire. But my mind was playing tricks on me.

I found Chara in her bedroom, sitting cross-legged on the bed, her back facing the mirror, naked from the waist up, her tiny ten-year-old breasts just appearing, round and soft, egg-like, brand-new. She doesn’t pay them any attention. At her age, I was dying to buy my first sports bra from C&A. But Chara doesn’t want to focus on her future; her eyes are on the past.

She was peering over her shoulder, eyes fixed on her reflection.

“I can’t really see it,” she said. “How does it look now?”

We do this every day: record the changes with words. In the last two weeks, less has changed.

I sat down beside her and ran my fingers along her scar, which stretched from shoulder to shoulder and down her spine.

“It’s such a beautiful tree,” I said, “almost exactly like the ancient chestnut tree in the forest. Can you feel the bark?”

She nodded.

“And the branches?”

“Crooked and long,” she said.

“Without leaves,” I added.

“And no chestnuts yet.”

“It’s a bare tree,” I said. “You can see its bare beauty, its grooves and curves and all its potential for new life.”

Chara was no longer looking over her shoulder; her gaze had settled on the magnolia flowers on the duvet cover. She was lost in thought. Then she said, “Thanks, Mamma,” and turned to give me a kiss on the cheek. It was the most tender kiss. A whisper. It held secrets of both love and resentment, hope and fear. It was so soft, as if she was afraid to assert any of those feelings too strongly.

Since the fire, her love has become delicate: she lives life as if she is holding a butterfly in her palm, afraid that it will die. Before the fire, she was fierce, yes, with everything out there—or at least as much of it as she could already understand; her love was wild and ruthless. If she believed something, she would make sure she was heard. If she felt something, she expressed it with passion. This was how I had taught her.

Now, she is as quiet and subdued as our surroundings.

I thank the heavens that my daughter is alive. But she is a ghost of herself. The fire has stolen her, too.

So, this morning, I was out for a walk, as usual. Rosalie must have smelled him, because she ran off the dirt path, panting; I followed her paw prints.

Mr. Monk was leaning against the ancient chestnut tree, staring up at the sky. His blue eyes.

No. I can’t think about this now.

Seeing him has brought it all back. It’s pressing in on me, the fire. It’s seeping in around the doorframe of my bedroom; it’s making the necklace around my neck tingle with heat, turning the whites of my eyes red, filling my lungs.

But I won’t cry. I have cried too much.

Maybe I can write it down. Maybe, that way, I can allow myself to remember without burning. Remember it as if it is a story from long, long ago. A fairy tale with a happy ending, like one of those in the beautifully illustrated books on the shelf in Maria’s Kafeneon.

I will call it

The Book of Fire.