Excerpt

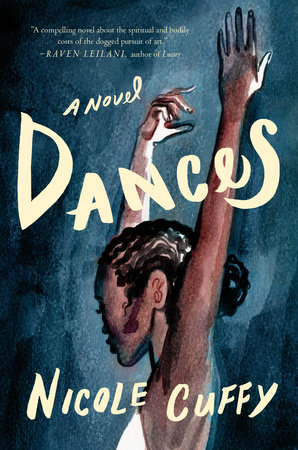

Dances

[barre]

The princess has shed some of her earlier shyness and learned to trust her suitors. Her smile is as confident and bright as a new coin; gone is her earlier hesitation. There is plain, fresh-faced gratitude as she accepts a rose from each of her suitors. The roses are bright, white, scentless. She throws them, not cruelly but joyfully, almost ecstatically. It has been some fresh miracle, learning to trust these four princes, a dawning. No one has hurt her yet. She has not been hurt a day in her life, in fact, never so much as pricked her finger. She suspects that there is no such thing as suffering. She understands suffering in the abstract—it is what made her shy of her suitors at first, but that they have not caused her pain makes its possibility even more remote. No one has let her down yet. She can almost believe there is no such thing.

I am the princess.

My reality is dual: I am Aurora, the white princess, just turned sixteen, who knows no suffering, and I am also Cece, the Black dancer of twenty-two, whose toes are screaming from being en pointe for so long, who is sweating like a slave, and whose ankle is throbbing distantly from a slow-healing sprain. I am counting as I dance—there is little room in my head for much else, though for a flash I do wonder if I feel up to holding that last balance for a couple of extra beats. I step forward, taking my suitor’s hand as I rise en pointe in attitude derrière, ready for the first promenade. I am turned 360 degrees like a figurine, pivoting on the toes of my pointed foot, ankle protesting just outside the gates of my attention. I won’t hold the balance too long, but I’ll make sure to get my leg up nice and high in the arabesque to make up for it.

My second suitor approaches, and I steady myself, signaling the first suitor with a quick squeeze when I am ready for him to let go of my hand. For a brief moment, I am unsupported—or rather, I support myself—balanced on one leg. I bring both arms overhead in fifth position, the space between them an imaginary crown, and then I bring my arm back down, give my hand to the second suitor. Second promenade. I do this four times in total, ending with my high, unsupported arabesque. The music is swelling, the orchestra creating a big inhale. I tease the conductor a little bit by making the last supported pirouette a triple—he controls the music to match me. I smile mischievously at an audience I can’t see beyond the lights. The music thuds to its dramatic conclusion as I flourish my arms in third position.

Oh Tchaikovsky, I think.

At the barre, I drown out the clunky, repetitive accompaniment by playing Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto in my mind. Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich—those were Paul’s favorites. Demi-plié and then grand plié, butt low to the ground, knees reaching over the second toes. Tendus, foot caressing the floor and then pointing:

front, front, front fifth, front fifth, side, side, side fifth, side fifth, back, back, back fourth, back fourth, temps liés. And then dégagés, slow and fast, the foot caresses and then flies—

front, side, back, side, side, back, side, front. Rond de jambe, the foot sweeping graceful half circles into the floor, and fondus and développés, the legs growing long now, delicious bloom in the hips and the inner thighs. Frappes, the legs loose at the knees, the feet playful. And finally, grand battements, lifting high, throwing the leg front, side, back, side. Company class is both repetitive and vital.

Alison is one of my favorite ballet mistresses at the company. She is perpetually in a good mood, her combinations are thoughtful, her corrections precise and gentle. She is in the middle of the room now, humming to herself and doing a kind of half dancing, sketching. I barely have to listen as she sets the next steps. I have been taking class with Alison since my student days at the School of American Ballet. The New York City Ballet does not hold open auditions; it pulls its dancers from SAB. Every class was a battle raged against imperfection. I remember the desperate thrill of it, the hunger. I stood out because of my Blackness, and I was determined then to obliterate it, to render my Blackness irrelevant with perfection.

Kaz, NYCB’s artistic director, took an interest in me early. He would slip into a class of young dancers, study us with his trademark stare. And he’d stop in front of me, watching me up close, very rarely offering a correction—only looking. To have Kaz’s eye on you was like an anointment, his very gaze material, an investiture. His fascination with me was unnerving, terrifying. His visits to classes were unpredictable. I never knew when he would be watching me, and so I had to constantly be perfect, beautiful. I was the only Black face in a sea of white and tan; I could not be anything but visible.

The pressure was enormous. I couldn’t have a bad turn day, or a fat day, when, no matter which clothes I wore, which mirror I checked, which angle I viewed myself from, all I saw was my body taking up too much space. When my knee started to ache, I couldn’t sit out for the big jumps at the end of class. I was a brick-brown kid from Brooklyn. There were people around me—students and faculty alike—waiting for proof that I couldn’t be graceful, that I was too heavy, too muscular, that my feet were too big, too flat, that I wasn’t classical. Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

I mark the little flourishes, the movement phases with my hands and feet, and then my body knows what to do. This has always been a skill of mine, remembering. I have been doing this routine—or variations thereof—every day for seventeen years. It is as ingrained in me as the movements required for tying my ribbons. I don’t have to think about it. Instead, I return to a favorite daydream of mine: I see the curtains rising, and the violin concerto is inflating, an orchestral bubble, and I can never work out whether it is I who appears first or my brother. Dwelling on Paul is a precious and carefully rationed indulgence. I just want him to see me now.