Excerpt

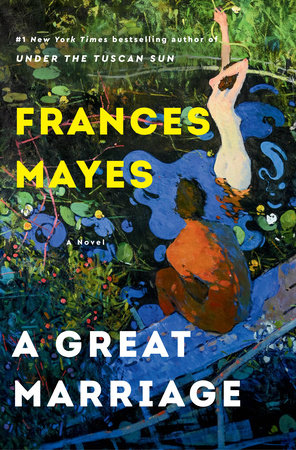

A Great Marriage

1The wine spilled. As I reached across the table, my sleeve grazed Austin’s glass and the big globe fell over, quickly spreading a circle of carmine red on the white tablecloth. Austin shot up fast, chair tipping backwards. He grabbed his napkin and spread it over the stain. I glanced at my daughter, bride-to-be Dara, her eyes widened, the slight quiver of her thin nostrils, a response Rich says she must have learned from her horse. She shot me a look—she knew I’d spent the afternoon lavishing my attention on every place card and dessert spoon. Rocco woke up from his nap by the door, barking and circling the table.

“Oh, no. Sorry!” I pressed my napkin into the dark stain, too, and moved the flowers and water carafe to cover it. Rich shooed Rocco out the door.

Austin dabbed at his tie with a cloth I grabbed from the kitchen. “Doesn’t matter, Lee—good as new,” he said. Austin’s unusual eyes—hazel, yes, but it’s the way he looks at you rather than their river-water color, as if he’s surprised to find you in front of him. But glad. (I’ve had the odd thought that he might say, I see you. Do you see me?) I rinsed his glass in the kitchen and Rich refilled. Austin raised it: “To Rich and Lee and Charlotte! I’m a lucky guy. Thank you for this feast, and thank you, Amit and Luke, for making the trip. And everyone,” he slightly bowed toward our friends, “I will be privileged to get to know you. Dara, you have my heart.” Nothing broke but the glasses all around clinked hard.

All solved, except not. Damn, the spilled wine seeped into the napkins.

For some moments, I just want perfection. Tonight was one, the intimate celebration—family and best friends—of my Dara’s imminent wedding to Austin. Dara, finally. After all her are-you-kidding-me romances—don’t think of the waiter with big buttons distending his ears, the modern dancer always slipping out of recovery, the too-blond scuba diver that time in Key West. Mama always said she’s glad of her granddaughter’s high spirits, but she’s one to overlook consequences. If we expressed misgivings, Dara always snapped, “Quit! Leave me alone. I’ve grown up in Hillston! And it’s not Thrillston here. I need life.” Many brief disasters, my bright bird, all soars and plunges. Now this opening into an exhilarating future. I was blessed, as they say around here, with meeting Rich, someone special. And now that’s her great fortune, too.

Her menu, my table—white linens monogrammed with Mama’s and her mother’s initials. The Waterford candlesticks we brought home from our honeymoon in Ireland, and two silver champagne urns (one borrowed from the florist) filled with apricot roses. Rich’s welcome-to-the-family toast, Mama on good behavior, for god’s sake, and Dara and Austin’s best friends, along with our dearest neighbors, Fawn and Charles, Elizabeth and Eric. Long and sparkling, two tables abutted, and the seam didn’t even show. Her intimate party: now marred. The night of the first photographs for the wedding albums—Jerry, our photographer friend, came for half an hour—to be pored over decades later, when I’m up floating in the clouds and they’re still walking the beach, paying taxes, and figuring out the great mystery ride that is marriage.

A small blip. No explosive political rants. As a state senator, Fawn can get going at times, and Eric, the town mayor, is often drawn into inflammatory discussions. Thankfully no oversharing or boring childhood anecdotes. A wine stain is not important. Rich is probably just mourning the waste of good Brunello.

Why am I careening in the sheets? Life right now seems a sweet unfolding. Dara’s radiance—her eyes, the aqua blue of the inside of a glacier, the only genetic gift from Rich’s overwound father. When she was small, I sometimes looked at her and wondered if she were an alien. Well, my cranky father-in-law did have those same eyes, but his were shaded by a burly monobrow, and his jaw was like the side of a meat cleaver, so you didn’t really notice the sublime aquamarine. Tonight, luminous, she looked at everyone with a vibrancy and joy I’ll never forget. We love Austin. Son we never got to raise? (My stillborn son when Dara was five. In thousands of moments I imagine our boy, Hawthorn Willcox, at six on a pony, at ten on the swim team, awkward at fourteen with peach fuzz. After all these years, I can barely say his name.) Is Austin my projection, is that why I attached to him from the start? The only solace for that lost oval face with faint blue-veined eyebrows and a fringe of eyelashes? I never saw his eyes but imagine them the color in that astronaut photo of Earth taken from space, swirling dark blue orbs.

Beside me, Rich sleeps like the newly dead. I almost laugh because his mouth in an O looks as if he’s about to blow a bubble. Just before he went to bed, he threw a few things in his bag for—where is he going? Investigating an environmental disaster in Alaska, I think he said. Oil. A spill. At least better than the last trip into Somalia, where the engine stalled and a gang of bandits tried to overtake the boat he and the photographer hired. Every night, as his head touches the pillow, he conks out for dreamless hours. I don’t envy him that—there’s something primitive about it—though my insomnia is crazy-making and something equally primitive lurks there, too. His snoring does make me laugh. Alpha bear guarding the cave entrance?

Rich hears the bedroom door creak, then click shut. She’s wandering, as usual. Lee often doesn’t know what sleep is. I left her a melatonin by her toothbrush before I signed off. This day lasted a week. I think the kids would have preferred to throw steaks on the grill, but I was told this had to be an occasion. Lee damned made sure it was. Dinner was memorable, those quail from our shoot down in Thomasville, near where Charlotte comes from. Odd to think of Lee’s mother as a South Georgia girl once upon some godforsaken time down in the pineys. At least the old bird behaved tonight. Unlike at Big Mann’s wake. Lord, when she stood by the casket at the funeral home and burst out with “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Flabbergasted the visitors who were there to offer condolences. And not only. She’d arranged for church bells to ring all over town after the service. Nothing grand enough for Big Mann. Rich smiled in the dark. A mother-in-law for the books. Someone should write a book. Her breed is disappearing—or never was. Who could write, Lee? Not me, no way. Being son-in-law is enough. Tomorrow—three flight changes to get to Fairbanks. A four-wheel waiting, the map in my backpack already marked. Lee will be alone, as much as she ever is, with Dara and Austin on their uncharted way and her mama heading south to her eagle’s nest at Indigo Island. Too damn bad Big Mann croaked. He was a right SOB, bigger than life.

Rich closes his eyes and lets himself travel around the table, looking at every guest, pegging each into the picture of Dara’s future. Best and brightest? Some of them. Moira, maybe not anymore. A future here in town writing for the Regulator News? So much for the Vanderbilt summa cum laude. Married to poker-face, frizzy-hair, what’s his name? Ear specialist in Lee’s dad’s old practice. Carleton, that’s it. Moira might turn into one of those who suck lemons for a living. He flashed on her and Dara bonding at nine over horse madness. Camps. Overwrought thoroughbreds snorting fog on winter mornings. Dara’s mess in the kitchen when she concocted grain and cereal mixes for the stable horses’ Christmas breakfast. Those tedious dressage shows. Hauling the horse in a wobbly trailer over to Winston and Charlotte. Dara, small on that beast Chelsea, sailing over jumps, trotting off with a big smile. Except when she didn’t. Two falls. Dislocated shoulder and jammed knee. Those gone days, thank you, Jesus. That horse we bought off the racetrack out to pasture somewhere. Mei Hwang, fragile. Thin as a straw. When I dropped off the dry cleaning, she was always there, little thing cutting out paper patterns, her parents taking in the shirts. Now she designs. Even making Dara’s wedding dress. Rich smiled again, remembering Dara telling him Mei used to try on the dresses and sweaters women brought in to be cleaned. Daringly wore some to high school games. Spunky girl. The two guys, Austin’s friends, arriving today, out tomorrow early. Big lives under way. Luke something, the American one, from Florida somehow got himself to Cambridge. Architect, too. All architects wear black and those thin glasses? Big smiles to match big lives, especially the Indian guy, Amit something. Luke seemed to lean toward the Hwang girl. Humble family, but this girl emerged with a cool natural dignity and poise.