Excerpt

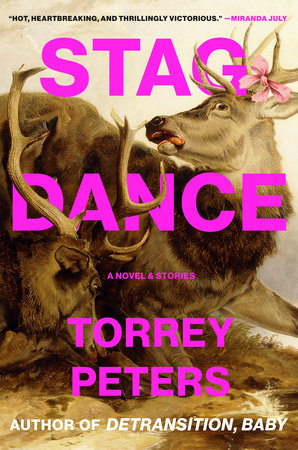

Stag Dance

Tipton, Iowa, seven years after contagionI’m lugging a bucket of grain for the sows, using two hands to keep the weight of it, hung from that thin wire, from biting into my somehow never-callousing fingers, when Keith comes up behind me and hoists it away from me with one hand. He holds it up, still with one hand, and tsks at me. “Looks like you need some help there, little lady.”

He’s got the macho bravado of all the T-slabs, complete with the aggression and rages—plus he’s six foot five if he’s an inch. Our relative heights place my line of vision at his chest, so I’m able to observe from up close how he wears a pair of old Carhartt coveralls unbuttoned down the front to show off his hairy bitch tits. He’s so proud of them that even out here in the country he shows them off, a bit of conspicuous consumption that even the most isolated farmers can read: I’m so flush with testosterone that I overinject. How about that, you low-count ration-dependent weaklings? I’m grateful he doesn’t wear shirts with the chest cutouts, a recent fashion among the slabs.

In business, the customer is supposed to always be right, but Keith takes as his due the notion that he’s in charge, and I’m the little follower. He doesn’t have any idea that before the contagion spread, I was already trans, already injecting estrogen. He just figures I’m another auntie-boy, one of those males who couldn’t afford testosterone after all the hoarding during the Rift Wars and so began injecting poor-quality estrogen. Hence all the “little lady” stuff, which most folks would understand as a gibe about how auntie-boys were said to have survived the war. I let him assume that. I need the black-market estrogen he harvests from those ugly mutant pigs.

With estrogen tightly rationed and regulated, the provisional government allots the good E for women of promising fertility. An older woman would have to have a relative in government or have the money for a really well-placed bribe to get on the ration list. A trans woman? People still believe that we antediluvian trans women started the contagion. Even if we came out of hiding, there’s no bribe large enough to get us estrogen.

Keith is doing curls with the bucket of feed, making the veins in his forearm pop like creeping vines. I wait for him to finish, but now the game is to show that his strength can outlast my patience. I gesture to the sows. “You want to feed the pigs yourself? Go right ahead.”

He hands the bucket back to me. “Nah, I like seeing you prance and scurry away from them.” Feeding the pigs means getting in the pen and scattering all the grain, hopefully before one of the freakish monsters knocks me over to get a whole bucket of feed to herself.

“F*** you, Keith.”

“Ooh, sweetheart. You just let me know when and where.”

I’m paying Keith extra to learn pig husbandry, a pretext, while I wait for an opportune moment to steal a few piglets from him. Then Lexi and I will be able to raise our own drove of sows. Unfortunately, I’ve come to hate the creatures—both Keith and the pigs. Keith for obvious reasons, and the pigs because they’re genetically modified to overproduce hormones bioidentical to those that humans used to produce, back before the contagion. Industrial-grade hormones in my body make me a crazy bitch, and I’m not six hundred pounds with inch-long razors for teeth. A month ago, I broke a toe kicking one of those porcine tanks in the snout. She wasn’t slowed for a second. Just barreled me over and bit a two-inch gash into my thigh when I didn’t immediately dump the feed bucket for her gustatory delight. Another scar.

I manage okay this time—even get a short retaliatory kick in on the black-and-pink one as I hop the fence out of the pen. The monster doesn’t notice, but Keith, leaning against the doorframe at the edge of the barn, does.

“Is it your time of the month or something?” he calls out. As if. He shakes his head. “You’re bitchier than my pigs. Save some supply for the real girls, huh?” He assumes I’m just a typical dealer, selling to women desperate for fertility and pregnancy. That’s what most of his stock goes for—the population is aging, dwindling.

I pick a strand of muddy straw from my pants as I walk over to him. “No periods yet. Are you holding out on the good stuff, Keith?”

He pulls from his pocket a little baggie with ten 5-mL glass vials inside. “This here’s pure. Enough to make a baby factory run for a month. Probably even make an auntie-boy like you preggo.”

I hold out my hand, but he doesn’t move to give me the vials sitting in his fat paw. Just leers at me. “Any of your girls need a stud, you know where to find me.”

“Sure, Keith.” He says this every time I re-up, but for once, I indulge a moment, contemplating the image of Keith trying to seduce and mount Lexi. It’s a funny, satisfying picture. He’d have just enough time, before she ended his stupid existence, to raise those white-blond eyebrows in surprise at what he found.

Seattle, contagion day

Lexi pulls up the hem of her skirt, showing off her thigh, more tattooed than when I last saw it. “See that?” she asks. I’m not thrilled with the vibe. Lexi has to know showing off her thighs won’t have the desired effect on me.

“See what?” I ask.

“Here,” Lexi says, and points. Above a tattoo of a ship is another simpler tattoo, maybe a stick and poke. It reads t4t.

“T4t?”

“Yeah,” Lexi says, “like we used to be. Or maybe you never really were.”

“Lexi, can we not do this again?”

She lets her skirt drop, covering the tattoo. “Fine. Anyway, now it’s different. I’m t4t for you in the abstract. Trans girls loving trans girls. And you’re trans, so you’re included.”

My annoyance flares: Lexi, deigning to include me in whatever she’s up to now. But she’s half right; Lexi’s somehow ended up maven of the Seattle trans girl scene, and I want to be included. The year during which she and I weren’t speaking was a lonely one. “So what do I get to be a part of?”

“The future,” answers Lexi. “In the future, everyone will be trans.”

I resist an urge to roll my eyes. Often, Lexi sounds like a sophomore who’s just enrolled in a critical theory course. I can’t tell if the other girls listen to her despite her super-basic analysis or because of it. Everything with her and her clique is gender theory, or else it’s transphobia, abusers, outrage, and Down With Cis!

I guess I didn’t fully resist that eye roll, because she pulls back and says, “Oh, I don’t mean that everyone will be trans in some squishy philosophical way. I mean that we’re all gonna be on hormones. Even the cis.” She reconsiders the wording of her statement and then revises: “Especially the cissies.” She’s got a plastic canister next to her that she fetched a few minutes before. She picks up the canister and taps on it ceremoniously. “You’ll see. When I say the future, I don’t mean some distant era. I mean in about six months.”

“Lexi,” Raleen says. “Don’t, please, just put it back.”

Her voice is nervous. As always, I’ve forgotten about Raleen, because she barely speaks, and even when she does, she hardly makes sense. Somehow, even though she stands a half foot taller than me, in the unobtrusive way she folds herself she appears to take up less space than a child, receding into the couch that is her temporary home until I forget about her once more.

We’re sitting in the living room of the shared house Lexi lives in, a falling down Victorian on the edge of the Capitol Hill neighborhood in Seattle. Even with the siding falling off, Lexi and her roommates shouldn’t be able to afford it, except that it belongs to the uncle of one of the girls, who rents it cheaply while he waits for a developer to come along and offer the right price. To atone for accepting a cis dude’s charity, Lexi offers the couches downstairs to any passing trans woman without a steady place to sleep. For the past few months, it’s been Raleen, who’s apparently homeless, despite her enrollment as a NSF-funded graduate student in molecular biology at the University of Washington. She began transition halfway through her dissertation research, and her faculty mentor lost interest in advising and collaborating with her. Her parents, back home in Podunk, Nowhere, have no idea about her transition, and it seems to be in order to draw out their ignorance, as much as for herself, that she shows up at the lab from time to time and putters around, while everyone waits for the last of her NSF funding to run out. She’s been on 2C-B half the times I’ve seen her, which Lexi says Raleen has synthesized herself. It’s some hallucinogen that is apparently easier to produce than LSD, at least with the chemicals Raleen has access to at her lab. Maybe she’s on it today; maybe that’s why she’s all nervous? Or maybe she’s just a weirdo.

“Raleen, we talked about this,” snaps Lexi.