Excerpt

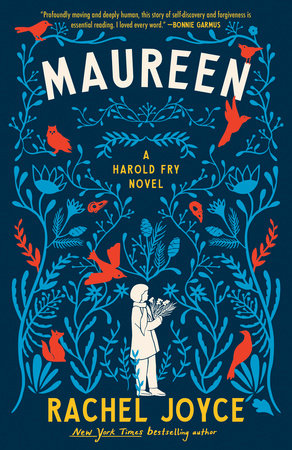

Maureen

Chapter 1

Winter JourneyIt was too early for birdsong. Harold lay beside her, his hands neat on his chest, looking so peaceful she wondered where he traveled in his sleep. Certainly not the places she went: if she closed her eyes, she saw roadworks. Dear God, she thought. This is no good. She got up in the pitch-black, took off her nightdress and put on her best blue blouse with a pair of comfortable slacks and a cardigan. “Harold?” she called. “Are you awake?” But he didn’t stir. She picked up her shoes and shut the bedroom door without a sound. If she didn’t go now, she never would.

Downstairs she switched on the kettle, and while it boiled, she got out her Marigolds and wiped a few surfaces. “Maureen,” she said out loud, because she was no fool. She could tell what she was doing, even if her hands couldn’t. Fussing, that’s what. She made a flask of instant coffee and a round of sandwiches that she wrapped in clingfilm, then wrote him a message. She wrote another that said “Mugs!” and another that said “Pans!” and before she knew it, the kitchen was covered with Post-it notes, like small yellow alarm signals. “Maureen,” she said again, and took them all down. “Go now. Go.” She hung Harold’s wooden cane from the chair where he couldn’t miss it, then slipped the Thermos into her bag along with the sandwiches, put on her driving shoes and winter coat, picked up her suitcase and stepped out into the beautiful early morning. The sky was clear and pointed with stars, and the moon was like the white part of a fingernail. The only light came from Rex’s house next door. And still no birdsong.

It was cold, even for January. The crazy paving had frozen overnight and she had to grab hold of the handrail. There were splinters of ice in the ruts between stones, and the front garden was no more than a few glass thorns. She turned on the ignition to warm the car while she scraped at the windows. The frost was rough, like sandpaper, and lay as far as she could see, slick beneath the street lamps of Fossebridge Road, but no one else was out. It was a Sunday, after all. She waved at Rex’s house in case he was awake, and that was it. She was going.

Road-gritters had already passed through Fore Street, and salt lay in pink mats all the way up the hill. She drove north past the bookstore and the other shops that would be closed until Monday, but she didn’t look. It was a good while since she’d used the high street. These days, she and Harold mostly went online, and not just because of the pandemic. The quiet row of shops became night-lit rows of houses. In turn they became a dark emptiness with a closed-down petrol station somewhere in the middle. She passed the turning for the crematorium that she visited once a month and kept driving. Now that she was on the road, she felt not excitement, but more a sense that, even though she didn’t know how to explain it, she was doing the right thing. Harold had been right.

“You have to go, Maureen,” he’d said. She had come up with a list of reasons why she couldn’t but in the end she’d agreed. She’d offered to show him how to use the dishwasher and the washing machine because he sometimes got confused about which buttons to press and then she wrote the instructions clearly on a piece of paper.

“You are sure?” she’d said again, a few days later. “You really think I should do this?”

“Of course I’m sure.” He was sitting in the garden while she raked old leaves. He’d done up his coat lopsided, so that the left half of him was adrift from the right.

“But who will take care of you?”

“I will take care of me.”

“What about meals? You need to eat.”

“Rex can help.”

“That’s no good. Rex is worse than you are.”

“That is true, of course. Two old fools!”

At this, he’d smiled. Only, something about the completeness of his smile made her miss him without even going anywhere, so that he could be as sure as he damn well liked, but she wasn’t. She had put down her rake. Gone to him and redid his buttons. He sat patiently, gazing up at her with his delft-blue eyes. No one but Harold had ever looked at her like that. She stroked his hair and then he lifted his fingertips to her face, and drew her down to his, and kissed her.

“Maureen, you won’t feel right unless you go,” he’d said.

“Okay, then. I’m going. I’m going, and nothing will stop me! Though, if you don’t mind, I won’t walk. I’ll take the more conventional route, thank you very much. I’ll drive.”

They’d laughed because they both knew she was doing her best to sound bigger than she felt. After that she went back to raking the leaves and he went back to watching the sky, but the silence was filled with all the things she did not know how to say.

So here she was, with Harold in her head, while she traveled further and further away from him. Only last night he had cleaned her driving shoes and set them, side by side, next to the chair with her clothes. “I won’t wake you in the morning,” she’d promised, as they got into bed and said good night. He had held his hand tight round hers until he fell asleep, and then she had curled up close and listened to the steady repeat of his heart, trying to take in some of his peacefulness.

Maureen drove slowly but there was hardly any traffic. If a car came toward her with its headlights shining, she saw it in plenty of time and pulled over in the right place—she even waved a polite thank-you—then the lanes were dark again, just the swing of hedge and tree as she passed. From there, she joined a dual carriageway and that was even better because the road was straight and wide and still pretty empty, with lorries parked in lay-bys. But as she got closer to Exeter, there were lots of roadworks, exactly as she’d dreamed during the night, and she got confused by the detours. She was no longer on the A38, but instead a chain of bypasses and residential roads, with many mini-roundabouts in between. Maureen drove for another twenty minutes before it occurred to her that the yellow diversion signs had stopped a while back and she had come to the edge of a housing estate. All she could see were blocks of flats and bony trees growing in spaces between paving slabs. It was still dark.

“Oh, well, that’s great,” she said. “That’s marvelous.” It wasn’t just herself she spoke to. She also had a habit of talking to the silence as if it were deliberately making things difficult for her. Increasingly she could not tell the difference between what she thought and what she said.

Maureen passed more flats and more tiny trees and cars parked everywhere, as well as delivery vans on the early shift, but still no sign of the A38. She turned down a long service road because there was a row of bright street lamps in the distance, only to find herself at the bottom of a dead end, with a large depot to her left that was surrounded by a set of open gates and spiked fencing.

She pulled over and got out her road map but she had no idea where to start looking. She turned on her mobile but that was no use either, and anyway Harold would still be asleep. For a moment she just sat there. Already confounded. Harold would say, “Ask someone,” but that was Harold. The whole point of driving was that she wouldn’t have to deal with people she didn’t know. “Okay,” she said firmly. “You can do this.” She would take her map and be like Harold. She would ask for help at the depot.

Maureen got out of the car, and at once she felt the cold against her face and ears and inside her nose. As she crossed the car park, security lamps snapped on to her left and right, almost blinding her. She could make out light from a prefab cabin to the left of the main building but she had to go cautiously, with her arms shot out to keep her balance. Maureen’s driving shoes were those flat suede ones with a bar across the top and special gripper soles; they were good on wet pavements but nothing was good on black ice. There were notices with pictures of dogs, warning that the premises were regularly patrolled, and she was afraid they might come running out. When she was a child, the local farmer had let his dogs roam freely. She still had a little scar beneath her chin.

Maureen rapped at the window of the hut. The young man on night duty wasn’t even awake. He was hunched in a fold-out camping chair, the turban on his head crushed against the wall, his mouth agape and his legs sprawled all over the place. She knocked again, a bit louder, and called, “Excuse me!”