Excerpt

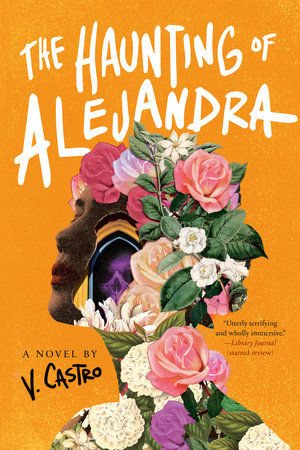

The Haunting of Alejandra

Alejandra

Philadelphia—2019Alejandra sat beneath the square showerhead in their newly refurbished bathroom. Her feet touched the glass, and her head leaned against the tiled wall. The bathroom was the only place in the house where she could lock the door.

She felt numb as she imagined her mind and body crumbling, her every cell fragile as limestone. The image came to her of a skull, like the ones from centuries ago at the bottom of cenotes in Mexico. For the last four years, she had been that skull.

The doorknob jiggled.

“Mom, Mom, hurry up,” a small voice called for her over and over.

Just five minutes. One minute.

Please.

One second alone to breathe?

She looked toward the door. Her body trembled with the overwhelming desire to shrink to the size of the blood clots trailing down her legs.

Her period arrived like clockwork every month—the only thing she could predict after her tubal ligation. No more children. Never again.

She already had three children. Each birth had left an open wound where each of those pieces of flesh had been hacked off from her.

Since then, Alejandra’s inner world had felt like the scary part of death: They say nothing exists after the brain short-circuits to darkness and the heart squeezes out its last bloody tears. And that was her. For years she abandoned herself to be a willing sacrifice to please everyone around her, and now nothing existed within her anymore. Even her own hand was not a hand at all, but a blade she used to carve her heart for anyone who asked her for it.

Beyond the beaded veil of water on glass, a white form appeared in front of the towel rack.

Alejandra didn’t have her glasses or contact lenses on. It was likely just steam. Or was it her towel? She could have sworn she’d hung it on the hook behind the door. She glanced in that direction. The towel was there. She turned back to the rack, her neck popping from the quick movement.

The form lingered.

What could have been a towel now appeared to be a torn dress. It looked almost like a white mantilla. Her poor vision moved in and out of focus.

From the center of the silhouette rasped a voice so minute it might have come from her own mind.

“You want to end it. Let me help you.”

Alejandra whispered back with the sensation of hot water burning her throat, choking her: “No.”

The steam billowed with the water. It reminded her of the day she’d tried on wedding dresses.

A loud bang on the door made her head jerk and legs tense as they folded into her body. “Alejandra, it’s dinnertime. Are you coming down to cook? The kids are hungry.”

Her eyes broke from the amorphous figure to the door then back again.

The figure was gone.

“Give me a minute,” she called out as best she could through her tearful confusion.

“All right, but you’ve been in there over twenty minutes.”

Matthew’s voice brought her back to the present, the reality she wanted to escape from. His voice had a childish whine. His footsteps down the stairs could be heard through the door. She was relieved he would not be lingering in the hallway to question her further. She rose from the floor to rinse the blood from her legs. Her duties waited, leaving her no time to wallow. Now all she could think about was her hope that the children would actually eat what she cooked. Or would it be another mealtime of watching them spit it out? Every time they did, a feeling of rejection burrowed into her like termites.

Alejandra turned off the water and stepped out of the shower to dry herself quickly before they called to her again from outside her door. She couldn’t stand to hear any of them repeat her name. Her anger would flare up—aimed at herself for being weak. Sometimes her knees threatened to buckle when she thought of how she didn’t own a single thing in the world. She had no money of her own. No job. Her name was not even on any of the bills. Half her life lived as a shadow.

As she ran the towel down her legs, she noticed a slimy substance on the glass door where the hallucination had appeared. It’s probably from the children, she told herself. Alejandra put on sweatpants and a T-shirt, then wrapped her hair in the towel.

Before leaving the bathroom, she paused with her hand on the light switch. Something as deep inside her as the lining of her uterus told her what she already knew: What she had seen was not a hallucination. The presence of something or someone lingered in the heat of the room. She could tell by the way the mist parted and shifted.

Alejandra held no illusions of having any value in the world. But her emotional and mental instability felt monumental, like a large wave in the distance. She felt it gaining height and speed before it crashed onto the shore and pulled her into the depths of the unknown.

She switched off the light, then rushed to the kitchen. The staircase creaked beneath her feet with each step. She paused when she reached the bottom. The stained-glass window in the front door caught her eye. Fractured yellow-and-red light splayed across the floor in broken shards. Her maternal instinct told her to sweep them up to prevent anyone getting hurt by them. A darker instinct told her to use one of them on herself to no longer feel the pain.

But even if they had been real glass shards, would she have had the energy to grab one of them and plunge it into her flesh to end it all? She remembered the encounter in the bathroom and the imagined words, “You want to end it. Let me help you.” She placed both hands over her face as if to block the images and sounds her mind was conjuring that could not possibly be real. Only her pain was real, because it was always sitting on her shoulder.

From the kitchen, the voices of the children bickering and Matthew telling them to stop broke her thoughts of death.

You are still adjusting to the new house. Get a grip, she told herself.

Just three weeks ago, they had moved from Texas to a quiet and leafy suburb of Philadelphia. Matthew had gotten a new job that offered a salary and bonus that they could not turn down, and this large six-bedroom house was one of the many luxuries afforded by his new position.

She had tried to overlook the fact that she didn’t much like the neighborhood, the school run commute, or the repairs that would inevitably fall to her to oversee. But the move made sense for Matthew, and the space was more than most people could hope for. Be grateful. Don’t start, Alejandra, she told herself. It was meant to be a long-term, putting-down-roots kind of home. So why didn’t it feel like home?

She had brought just two things to remind her of her birthplace. One was the Frida Kahlo coffee table book she found at a secondhand store before leaving Texas. The cover was the painting of Frida in her white back brace and flowing white skirt against a barren background. Tears streamed from her eyes, yet her face remained stoic. Inside of her was a crumbling Doric pillar.

The second was a photo of Alejandra and her birth mother, Cathy, displayed in the hallway. It had been taken in the coffee shop they regularly met in. They were both smiling. Alejandra wanted to smile like that again. And she wanted to tell Cathy what was going on inside her, but she didn’t want to spoil their budding relationship; they had only just met when Alejandra moved away.

The bickering in the kitchen grew louder. Matthew stood in the kitchen with the same curious look as the children as she entered. “What took you so long?”

She inhaled a deep breath. Her impatience with him was something not easily washed away in a shower. “You could have started making dinner.”

He gave her a wide smile and furrowed his brow. “But that’s your thing. I don’t know what you have planned because you buy all the groceries. You always do the cooking.”

Her belly sank as she envisioned a snapshot of cooking for him for the next fifteen years. But the children were listening to their conversation, especially nine-year-old Catrina, who was waiting for her mother’s response with an expectant stare. Alejandra couldn’t deal with this now. The steam from the shower had somehow carried itself into her head in the form of a heavy exhaustion. “Can you at least wipe down the table?” she asked Matthew.

He glanced back at the glass tabletop. “Yeah, sure. It’s disgusting from whatever they ate earlier.”

Alejandra walked to the fridge to take out something that would expire soon and would make a meal with minimal effort. She used to love to cook, but it had become a chore. The thought of ordering food crossed her mind until she imagined the conversation that would ensue as they tried to decide what to order. They had reached a place in their relationship where they couldn’t even agree on Indian or Chinese.

She grabbed a bag of prechopped vegetables and an easy roast-in-the-bag chicken with new potatoes. One pot for the vegetables and the one roasting tray for the chicken to toss in the oven. It would take just over an hour for it to be done. Two episodes of some cartoon on Netflix would keep the kids quiet with Matthew sitting next to them. She hoped that they would remain in the other room because her patience had evaporated like water left to simmer to the bottom of a pot. It wouldn’t be long before something inside of her burned.