Excerpt

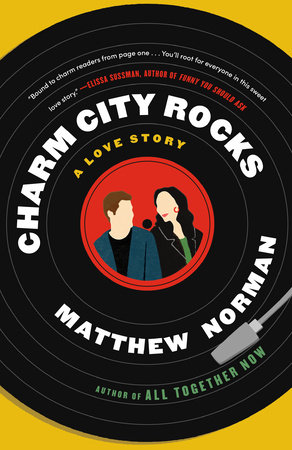

Charm City Rocks

Chapter 1Here’s an interesting fact about Billy Perkins: he’s happy. No, for real, legitimately. It’s kind of his thing, actually. If a person can have a thesis statement, that’s Billy’s: I’m happy. And, well, why wouldn’t he be?

For starters, he has the most fantastic apartment. It’s the perfect size—just big enough—and it’s directly above a record shop called Charm City Rocks, so the place vibrates gently with music, as if the walls are living things that hum along. He loves his neighborhood, Fells Point in Baltimore, with its cobblestone streets and loud bars and the gourmet pretzel stand that makes his block smell like baking bread. He even loves Baltimore, because there’s something thrilling about living in a city that the rest of the country assumes is on the verge of collapse. There’s a bumper sticker he sees around town, Baltimore: Actually, I Like It, and Billy couldn’t agree more.

He’s an independent music teacher—the founder of Beats by Billy LLC—and he loves that, too, as far as jobs go, because he gets to set his own hours and spend his days teaching people the sheer joy of rocking out, and he can wear whatever he wants. He goes with jeans and sneakers, mostly, along with an array of band T-shirts that his students have given him over the years. He’s been really into cardigans lately, too, because cardigans are the perfect garment, like, the convertible of sweaters.

He teaches kids and teenagers mostly, which is rewarding work, because he gets to shape young minds and pass on an appreciation for the arts. But there are some adults mixed in there, too, which is also gratifying, because it’s never too late to learn something new, right? His oldest student is a seventy-year-old widow named Alice who always wanted to play the guitar. She meets with Billy twice a week instead of the standard once because she’s determined to play a rock-and-roll medley at her daughter’s wedding reception this summer. Plus, as she told Billy during their first lesson, “Once you hit seventy, it’s best to get on with things.”

Many of Billy’s students came to him after flaming out with more traditional music teachers. Consequently, they often arrive to their first lesson shy and sullen, convinced that learning to play an instrument is lame or boring or just too much work. Billy always manages to break through, though. He’s not sure why; he’s just got a knack for it, he supposes. Or maybe it’s the cardigans. Along with being the perfect garment, cardigans are very disarming. We can probably thank Mister Rogers for that.

Back to Billy’s apartment, though.

The place is neat and clean and full of books and music and local art, and there’s a wildly complicated espresso machine that Billy inherited from his grandma that looks like something built by NASA in the sixties. As great as all those things are, the true star of the place is Billy’s Steinway & Sons grand piano. It’s the most expensive thing Billy owns, and it’s a straight-up showstopper. Even if you know nothing about pianos, and most people don’t, you know that the Steinway is something special. Plumbers or electricians will be over to fix something, and they’ll stop and say, “Jeez, look at that thing.”

Most mornings, particularly when it’s sunny, Billy opens his windows wide and loudly plays the most epic piano parts of classic rock songs, like “November Rain” or “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and people wave up at him while they walk their dogs or shuffle off to work. The beer delivery guys are some of Billy’s biggest fans. They sometimes shout requests, and he obliges as best he can, because playing music is such an easy way to make people happy. For example, just try listening to the intro to “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” by Journey without feeling at least a small rush of joy.

The thing Billy loves most, though—more than his apartment or his confusing espresso machine or even the Steinway—is his son, Caleb.

Caleb is goofy and sweet, and he pokes fun at the things his dad likes, but never unkindly. And on this particular Saturday night in early spring, Caleb is stretched out on Billy’s couch like a young giraffe in repose. Billy is sitting across from him in his rocking chair, which Billy refers to as “The Rocker,” and they’re watching a documentary series on Netflix called The Definitive History of Rock and Roll.

At this exact moment, 9:25 p.m. eastern standard time, there’s nowhere Billy would rather be, and there’s no one he’d rather be with. Billy hasn’t always been this blatantly sentimental, but Caleb is a senior in high school, so lately Billy has been thinking about the finite nature of . . . well, everything. But especially childhood.

If it were possible, Billy would go ahead and pause time right here. His apartment would hum on, the streetlights outside would hit the Steinway through the window just right, and his son would be here every other week forever, stretched out and lanky, being young and silly.

But that’s not how life works, is it?

“Did you get enough to eat?” Billy asks.

Caleb makes a noise—like a grunt of general affirmation.

“Come on,” Billy says. “Use your words.”

Caleb laughs, one of those fed-up teenager laughs. “Dad, stop it. I told you, I’m fine.”

“I bet Gustavo still has some pretzels left.” Billy goes to the window and opens it. Street sounds, like a ragtag orchestra, flood the apartment. “Hey, Gustavo!” he shouts. “You still have some warm ones?”

Down at Hot Twist, which is a pretzel stand along the brick sidewalk across the street, Billy’s friend Gustavo reaches below the counter like he’s checking, but when he pulls his hand back up, he gives Billy the finger. This has been Gustavo’s favorite running joke for more than a month now.

“That’s really funny!” Billy calls. “You should be proud!”

“Yeah, man, I have warm pretzels!” Gustavo shouts. “Having warm pretzels is literally my job! You guys should come down. We can eat, and you can watch soccer with me.”

From the window, he can see the TV mounted on the back wall over Gustavo’s shoulder. Elite athletes on a vast green field run and run. Billy gives his friend a thumbs-up and returns to The Rocker.

“He flipped you off again, didn’t he?” asks Caleb.

“He did.”

Caleb laughs. “Classic Gustavo.”

“Anyway,” says Billy, “if you want a pretzel, I’m buying.”

“Nah,” says Caleb. “I crushed three quarters of that pizza. I could probably barf.”

Billy looks at the picked-over remains of the Johnny Rad’s pizza on the coffee table. “You did, didn’t you? Where do you put it all, anyway?”

Caleb shrugs. “Maybe I’m still growing.”

What a thought that is. Caleb doesn’t do anything useful with his six-foot-six-inch body, like fight crime or play in the NBA. Still, his height is a source of constant pride for Billy, just another weird thing he loves about the kid.

Billy was barely in his twenties when Caleb was born. Being that young and a single dad had its challenges—like something in a think piece about woefully unprepared fathers. The upside, though, is that they’ve essentially grown up together, and now their relationship is like a parent-friend hybrid.

The documentary, which moves along chronologically, is currently analyzing the nineties, so Eddie Vedder is on the TV in a giant flannel mumble-yelling the song “Jeremy.”

“I don’t get the whole grunge thing,” says Caleb. “Was it, like, in the bylaws that clothes had to be way too big? And what’s he saying? You can’t understand him.”

Caleb has had a lot of opinions about the documentary series. His most unforgivable comment a couple of episodes ago was that maybe David Bowie should’ve just picked one look and gone with it.

After Pearl Jam, U2’s mid-career evolution comes up. Bono is dressed like a fly in a leather suit and wraparound sunglasses. “And what even is that?” asks Caleb. “Was he trying to be an asshole?”

“He was being ironic,” says Billy. “And don’t swear.”

This is something they’re working on: Caleb’s swearing. Billy is all for the subtle use of profanity, but too much just seems excessive, like saxophone solos in rock songs.