Excerpt

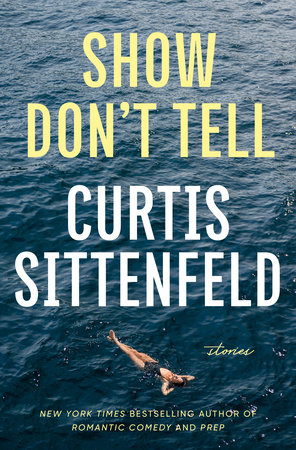

Show Don't Tell

Show Don’t TellAt some point, a rich old man named Ryland W. Peaslee had made an enormous donation to the program, and this was why not only the second-year fellowships he’d endowed but also the people who received them were called Peaslees. You’d say, “He’s a Peaslee,” or “She’s a Peaslee.” Each year, four were granted. There were other kinds of fellowships, but none of them provided as much money—eighty-eight hundred dollars—as the Peaslees. Plus, with all the others, you still had to teach undergrads.

Our professors and the program administrators were cagey about the exact date when we’d receive the letters specifying our second-year funding, but a rumor was going around that it would be on a Monday in mid-March, which meant that, instead of sitting at my desk, I spent the majority of a morning and an early afternoon standing at the front window of my apartment, scanning the street for the mailman. For lunch, I ate a bowl of Grape-Nuts and yogurt—Monday nights after seminar were when I drank the most, and therefore when life seemed the most charged with flirtatious possibility, so I liked to eat light on those days—then I brushed my teeth, took a shower, and got dressed. It was still only two o’clock. Seminar started at four, and my apartment was a ten-minute walk from campus. I lived on the second floor of a small, crappy Dutch Colonial, on the same street as a bunch of sororities and the co-op, where I occasionally splurged on an organic pineapple, which I’d eat in its entirety. I was weirdly adept at cutting a pineapple, and doing so made me feel like a splendid tropical queen with no one to witness my splendor. It was 1998, and I was twenty-five.

I was so worked up about the funding letter that I decided to pack my bag and wait outside for the mailman, even though the temperature wasn’t much above freezing. I sat in the mint-green steel chair on the front stoop, opened the paperback novel I was in the middle of, and proceeded to read not more than a few sentences. Graduate school was the part of my life when I had the most free time and the fewest obligations, when I discussed fiction the most and read it the least. But it was hard to focus when you were, like a pupa, in the process of becoming yourself.

My downstairs neighbor, Lorraine, emerged from her apartment while I was sitting on the stoop, a lit cigarette in her hand; presumably, she’d heard my door open and close and thought that I had left. We made eye contact, and I smirked—involuntarily, if that mitigates things, which it probably doesn’t. She started to speak, but I held up my palm, standing as I did so, and shook my head. Then I pulled my bag onto my shoulder and began walking toward campus.

Lorraine was in her early fifties, and she had moved to the Midwest the same week in August that I had, also to get a master’s degree but in a different department; she told me she was writing a memoir. I’d moved from Philadelphia, and she’d moved from Santa Fe. She was dark-haired and wore jeans and turquoise jewelry—I had the impression that she was more of a reinvented Northeastern WASP than a real desert dweller—and was solicitous in a way that made me wary. I wanted to have torrid affairs with hot guys my age, not hang out with a fifty-two-year-old woman. In early September, after sleeping at Doug’s apartment for the first time, I’d returned home around eight in the morning, hungover and delighted with myself, and she’d been sitting on the front stoop, drinking coffee, and I’d said good morning and she’d said, “How are you?” and I’d said, “Fine, how are you?” and she’d said, “I’m thinking about how the English language lacks an adequate vocabulary for grief.” After briefly hesitating, I’d said, “I guess that’s true. Have a nice day!” Then I’d hurried inside.

It was likely because I was distracted by Doug, and our torridness, that I hadn’t paid much attention at first to Lorraine’s smoking. I could smell the smoke from my apartment, and one day I even pulled out my lease, to check if it specified that smoking wasn’t permitted either inside or out—it did—but then I didn’t do anything about it.

In the fourth week that Doug and I were dating, his work and mine were discussed in seminar on the same day. Mine was discussed mostly favorably and his was discussed mostly unfavorably, neither of which surprised me. The night before, while naked in Doug’s bed, we’d decided to give each other feedback ahead of time. As he lay on top of me, he said that he liked my story, except that he’d been confused by the beginning. I then delivered a seventeen-minute monologue about all the ways he could improve his, at the conclusion of which he stood up, went into the other room, and turned on the TV, even though we hadn’t had sex. I believed that a seventeen-minute critique was an act of love, and the truth is that I still do, but the difference between who I was then and who I am now is that now I never assume that anyone I encounter shares my opinion about anything.

The next night, most people went to the bar after class; it was only eight o’clock when Doug said that he had a headache and was going home. I said, “But getting criticism is why we’re in the program, right?” He said, “Having a headache has nothing to do with the criticism.” Three hours later, after leaving the bar, I walked to his apartment. I knocked on his door until he opened it, wearing boxers, a T-shirt, and an irked expression. He said, “I don’t really feel like company tonight,” and I said, “Can’t I at least sleep here? We don’t have to do it. I know you”—I made air quotes—“have a headache.”

“You know what, Ruthie? This isn’t working.”

I was astonished. “Are you breaking up with me?”

“Obviously, we jumped into things too fast,” he said. “So better to correct now than let the situation fester.”

“I don’t think ‘fester’ is the word you mean,” I said. “Unless you see us as an infected wound.”

He glared. “Don’t workshop me.”

It’s not that I wasn’t deeply upset; it was just that being deeply upset didn’t preclude my remarking on his syntax. I walked to my own apartment, and I spent a lot of the next week crying, while intermittently seeing Doug from a few feet away in class and at lectures and bars.

Also during that week, I knocked on Lorraine’s door and told her that I could smell her cigarette smoke in my apartment and was respectfully requesting that she smoke elsewhere. She was apologetic, and later that day she left a card and a single sunflower outside my front door—when I saw the sunflower, I was thrilled, because I thought it was from Doug—and, judging from the smell, she continued to smoke enthusiastically. I left a note for her saying that I appreciated the flower but would be contacting our landlord if she didn’t stop. On Saturday, I returned home at one in the morning to find her sitting outside in the mint-green chair, enjoying a cigarette; I suspect that she’d thought I was asleep. She giggled and said, “This is awkward,” and I ignored her and went inside. The next day, I emailed our landlord. After that, I’m pretty sure that Lorraine neither smoked as much on the property nor completely stopped, and I continued to ignore her. That is, I said no actual words to her, though, if she said hello, I nodded my head in acknowledgment.

Another month passed, and one afternoon a commercial airplane crashed in North Carolina, killing all forty-seven passengers and crew members. The next day, Lorraine was sitting in the mint-green chair reading the newspaper when I left the apartment, and she said, “Have you heard about the plane crash?” and I said, “Yes,” and kept walking, and I had made it about ten feet when she said, “You’re a f***ing bitch.” I was so surprised that I turned around and started laughing. Then I turned around again and walked away.

Once more, a single sunflower appeared outside my door, along with another note: That outburst is not who I am. I admire you a lot. I had already repeated to my classmates the story of my middle-aged turquoise-jewelry-wearing neighbor telling me I was a f***ing bitch, and the note left me queasy and disappointed. In the next five months, right up to the afternoon that I was waiting for my funding letter, I interacted with Lorraine as little as possible.

It was, obviously, a reflection of how agitated the funding had made me that I’d sat on the stoop. As I walked to town, I began composing in my head a new email to my landlord. I would, I decided, use the word “carcinogenic.”