Excerpt

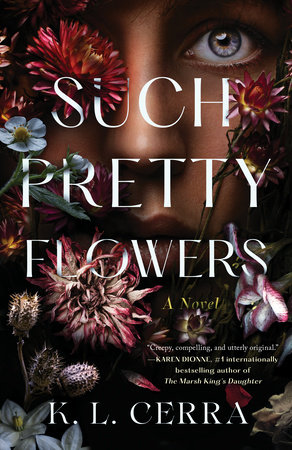

Such Pretty Flowers

Chapter 1Maura brought pomegranates to Dane’s funeral reception. It was an odd choice and I mentioned this to Rachel, the hard pew edge biting into my thigh.

“What’s wrong with pomegranates?” Rachel said.

I pictured a halved pomegranate. Those wreaths of slick, pink organs made my skin scuttle over my bones, just like when I looked too closely at a wasp’s nest or a strawberry. I’d googled the sensation: trypophobia. Fear of holes and circle clusters. But this felt too exhausting to explain in a whisper.

“Haven’t you heard of Persephone and Hades? Referencing eternal damnation to the underworld feels a tad insensitive, today of all days.”

Rachel’s cheek puffed. “Okay, Holly.” Her eyes were fastened on the pulpit where Maura stood.

I had no choice but to look, too.

My brother’s now ex-girlfriend was adjusting the stem of a tiny microphone. She had a face that made your mind itch as it tried to pinpoint what felt off. There was definitely something threading under the luminous skin. Inky princess tresses, black eyes, and sharp, birdlike bones that jutted at her clavicle. She wore a birdcage veil with pearled netting at an angle that fell a smidge short of jaunty. Seeing it—seeing her—gave me a jolt, like missing a step on my way down a staircase. Even speaking at my brother’s funeral, Maura needed to enrapture.

Dane had brought his new girlfriend to meet the family over Easter brunch, five months ago now. Back then, the two of them had been dating only a few weeks. Maura complimented the plasterwork of my childhood home in that musical voice of hers; uncharacteristically, Mom had nothing critical to say afterward. She has polish, was all she provided. It was undeniable: Maura had dazzled both of my parents. I think, on some level, they’d doubted Dane’s ability to land a girl like her.

As I sat in the pew, my fists fizzed with heat. We’d all doubted him, and now, here we were. How would things have turned out differently had we listened? It was a cruel game I often played during the long nights after his suicide when I knew sleep was futile. What if we’d tried a little harder? Rachel told me I couldn’t get swept away in what-ifs, but really, who was she to tell me that? She wasn’t the one fighting the riptide, feeling like the past was a puzzle. One that maybe, put together a different way, could have kept my little brother alive.

Maura slid a piece of paper over the podium.

Rachel put a hand on my knee as Maura started speaking. To my left, my mother’s shoulders rounded under her cardigan. I noticed a tiny, slack space between my dad’s lips. It reminded me of the way he’d looked when he’d told me what had happened to Dane two weeks ago—like he’d lost control of the bottom half of his face. It was the first time I’d seen his dad-armor slip, and I hated it.

The paper was, it turned out, an excerpt from

Charlotte’s Web. I had no idea why she’d chosen this. If we’re talking animal books, Dane had much preferred

Jumanji, leaning toward that edge of danger evident from the very first pages. Until his symptoms became evident a few months ago, he and I had been devastatingly close. I knew his taste in books.

Maura read from the paper with the voice of a jewelry-box ballerina. The quote she had chosen was from the spider’s point of view. I dug my fingertips into my thighs. Every word drove another hairline crack through me, fault lines multiplying and branching like veins. Then Maura flicked her eyes up at me. Saw me. It made me feel naked, my every thought exposed, and my throat closed in response.

I surged to my feet and pushed past my family in the pew.

Rachel found me doubled over in a restroom stall. I stared at the toes of her Mary Janes under the door, seeing stars.

“Holly,” she said. “Let me in.”

“No.”

“Come on. Open up.”

I unlatched and cracked the door. Rachel handed me a cup of tepid water. I took it and wet my bristly tongue. “God, this is embarrassing,” I said.

“What are you talking about? This is your brother’s funeral. You’re allowed to be upset.”

She was right—not to mention the fact that I’d been on the opposite side of the bathroom stall for Rachel more than a few times back at Emory in Atlanta. After graduation, though, the scripts flipped. Rachel met Henry when she stayed on at Emory for grad school, and all too soon, she claimed that trifecta of adult accomplishments: a master’s degree, an apartment, a fiancé. Thankfully Henry’s family hailed from Savannah, too, so I’d jumped at the chance to reclaim my college roommate. These days, Rachel was the singular grounding force in my life. But sometimes I missed the feeling of her leaning on me, the way she had back in college.

My hand shook as I pulled the cup away from my mouth, slopping a bit onto the bathroom tile. I wanted to tell Rachel that there was something else bothering me, but I couldn’t scrounge up the words. I set the empty cup on the back of the toilet and braced my palms on my thighs.

“I still don’t get what happened to him, Rach. That time I visited him in his dorm room, I had no idea he was so sick—”

“I know.” She let out a stream of air as her eyes jumped to the bathroom door. “I know.”

Something molten leapt up my windpipe. Rachel seemed more concerned about someone walking in and witnessing my breakdown than comforting me. As a therapist, shouldn’t she have been more adept at being—or at least appearing—present? I turned toward the toilet, feeling that heaving thing inside me. Somehow I’d managed to keep it at bay these past few days; I feared what might happen when I couldn’t any longer.

Sure enough, the restroom door flapped open, making us spin. An usher with prominent marionette lines at her mouth glanced at us before turning on the sink. As she soaped her hands, I stared at Rachel, smoldering. The left side of my roommate’s face jumped.

“I’m sorry,” she said, when the usher left. “I know this is hard, and we can talk more about this later. Okay? You wouldn’t want to miss what your brother’s girlfriend has to say, right?”

“No,” I relented, following Rachel out of the bathroom stall. My breath and heartbeat had smoothed by now, but my legs still felt liquid. I paused at the mirror to swipe at the bruise-colored hollows beneath my eyes. Today, their gray shade looked like an absence of color, a photograph negative. “Of course not.”

Mom, Dad, and I were the last to leave, just as the ushers descended on the tray of picked-over cucumber sandwiches. In line to exit the parking garage, Dad drummed his fingers on the steering wheel. It took him a few tries, inserting his parking slip into the stern metal machine mouth, until our fee registered.

“Third time’s the charm,” he said to the parking attendant who glared down at him from her glass tower. How would she feel if she knew this man had just left his son’s funeral? Would she dare look at him like that?

Mom sat silently in the passenger seat, rubbing her temples like she did when she felt a migraine coming on. As Dad eased us onto the main road, streetlights slivered in through the windows, illuminating the half-empty backseat. Dane always sat to my left. When he was little, he’d kick the back of Dad’s seat during long road trips. Dad would roar, threaten to pull over and make us change seats. These days, all I saw were the gashes that Dane had left in my life. I ran a finger around the rim of the cup holder between our seats, my throat thickening.

“Well,” Dad said, “I thought some of those speeches were really heartfelt. That kid from his class—Jordan?”

“Jacob,” Mom said. She didn’t turn to face him.

“Jacob, that’s right. Hope he’ll be coming to Dane’s showcase next month. But I didn’t see Dane’s friend Lauren. Did she make it?”

“I’m not sure.”

Silence.

“Anyway,” said Dad, trying again, “I thought the funeral home did a nice job putting everything on, didn’t you, Holly?”

“Yeah,” I said, at the same time that Mom said, “Hardly, Arthur. The food was mediocre and the sound system was unreliable. The floral arrangements were the only redeeming part of the event, and that’s only because Maura graciously stepped in and offered her services.”