Excerpt

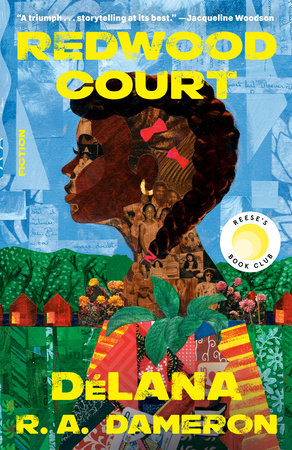

Redwood Court (Reese's Book Club)

Redwood CourtIt took thirty-two breaths to walk from Weesie’s front porch on the farm in Thomson, Georgia, to the county line, where the postman delivered their mail. Mostly bills, but sometimes a postcard or letter from her aunt Barbara who lived in “Chee-cago,” saying, Things are good, or Send money if you can, or Snow reached our windows for the third day in a row.

When Weesie stood on the porch, there weren’t any other houses for as far as the eye could see. There were other things she liked: being at the end of the singular road, so that if she heard the sherr and crunch of rocks under tires, that signaled someone was coming all this way intentionally to see about them; you don’t just pass by the end of a country road. And Weesie liked company. She felt her family didn’t get enough of it and wanted more. Even from the little glimpses of whatever life Aunt Barbara lived in Chicago, Weesie was jealous of her escape from farm life and its cyclical monotonies. That’s what happened with the younger generations. Yes, yes, Barbara was an “aunt,” because she was Lady’s little sister, but she was born a few years after Weesie. Because of the times and the place, Weesie, as young as she was, had to care about a harvest season, reaping and shelling the butter beans, cutting and drying the tobacco leaves. The long, drawn-out days of it all.

She never saw it with her own eyes, thank God, but the white folks were closing in on her family’s little piece of farmland, increasing their public acts of violence in an attempt to recover their dignity, first post-Depression and now post–World War II. Nothing was ever enough. Weesie couldn’t go into town unaccompanied, and Mann (what everyone called her father) had to teach her how to hold a steak knife in her waistband—instructed use: for emergencies only. Mann himself had to make sure all of his steps were ordered just to go and pay a bill or get some nails from the hardware store, lest he, too, be disappeared, and the family read about some hunter finding his body in the woods an indeterminate amount of time later. Lady (what everyone called Weesie’s mama) scoffed: Won’t it the tail end of the first half of the twentieth century? Still, they felt the need to tiptoe around. Was there anywhere Black folks could go to be free like they said they were supposed to be?

It was the body found hanging from the light pole that had sealed their fate in Georgia. He was so gone—the maggots having done their maggoty thing—no one who saw the body knew who he was. Signature white-folk moves. Story was told that whoever he was had been caught stealing a stamp from the post office. Later, folks learned Jacob was trying to write a letter to his cousin in Detroit, to see if any money could be sent down because the harvest won’t as strong this June ’cause of the drought and the air was as dry as a sack of flour and even the drought-resistant crops gave up the ghosts and burnt. Could you believe it? That’s what prompted Lady to start packing. Mann won’t dare picture himself in the city or noplace where you could see into your neighbor’s house just looking out the window, so he said he didn’t know where she was going—whatever this place was called Columbia—but he won’t be going with them. He had his shotgun, he said. Let them white folks come.

A month later Lady, Weesie, and her brother Pete were in Columbia, South Carolina, in temporary housing. They chose Columbia because it was due east and the first “big city” they got to, and also because some other family had made their way there in 1946 after the war dust settled. It had taken Lady two years to make the leap herself. Compared to Thomson, there were so many houses and buildings with multiple stories, you had to look up where you were walking to know where you were going. Everything in Columbia was hard roads and manicured trees. Folks were closer together; it was hard to see where you could go and where you couldn’t. Everywhere signs were shouting colored only / whites only and so forth. In Thomson, you knew on one side of the railroad tracks was for the whites and on the other side of the railroad tracks, down the road and around the corner, was for Blacks.

Here, you’d have a department store for whites, and across the street a department store for Blacks. When Lady got a job at Woolworth’s and needed something for the house, she had to clock out, walk across the street, and pay full price for the tea towels or frying pan. Then the white folks decided they wanted downtown to themselves, so she had to drive across town to buy the things she sold ten hours a day—only those items were whites-only items; she had to go use up her gas in search of the Black ones.

For Weesie, though, it all felt shiny, different. The front-lawn grasses were watered so much that it was too green to look real. Even the brick rows of two-room residences felt like a luxury: the bathroom was inside the building, even if you had to share with a neighbor. You knew you had arrived if you had one of those plug-in stoves to get cooking, and maybe best of all, some of the houses were hooked up so you turned a knob over the washtub and the water was hot. Even though it came out brown first and they had to run it ’til it ran clear, it was hot, automatic water.

So this was heaven.

Weesie loved to tell the story of how she’d first met Teeta at the collard-green stand. She’d say, “At the collard green in nineteen and fifty-two.” Teeta was unloading the truck early one Saturday morning and Weesie was coming for her bundles for Sunday supper. Teeta was pulling out a patch of mustard greens just as Weesie was walking up, and before he could put the bundle on the wood table, Weesie scooped them up.

“These my favorite. They sweeter than collards. Don’t need the sugar to take out the bite,” Weesie said. She smiled at him. Teeta tipped his hat and kept unloading.

If Teeta were there when Weesie was reliving those days, he’d say something about how he didn’t even know what Weesie was talking about. Greens is greens. He was just trying to make his five dollars for the day, so he could go to the pool hall later that evening before heading back to Green Sea on the coast until the next weekend. It won’t until she kept coming back and kept trying to grab his hands and the mustards that he started to think something. Finally, one day she asked his name. “Teeta,” he said, smiling. By then, Weesie had decided she would always be the one to make the collard run every Saturday, and every Saturday like clockwork, Teeta was there.

Until one day he wasn’t.

When word got around that they were requesting more men to support in Korea, Pete suited up for the navy. Lady did some scheme with the other Negro women managing the enlistment paperwork and her baby Pete came back beaming: he could stay stateside and clean the ships and manage the goings on in the shipyard. He only had to go an hour and a half away. This was relief enough for Lady and Weesie, though it felt eerily familiar to the tension in the air in Thomson just before they fled: every day, another Black man raptured into the sky. The third Saturday came and went without any sighting of Teeta. And then a new gentleman arrived managing the collard-green stand. He was older, probably not draft age—Weesie could tell because of all the grays and the ways his jowls hung low like Mann’s did the older he got. She asked the collard-stand owner where the young gentleman Teeta was these days and he said only, “They shipped him off.”

The sweet potatoes in her hand just about fell straight to the ground.

Of course, whole lives were lived in the years before Weesie and Teeta got married. But when Weesie tells it, it’s as if her life started when Teeta came back to Columbia five years after they first met and looked for her at the collard stand. Truth was the army shipped Teeta back to Green Sea, where he floundered for some time trying to land but couldn’t find a drop a work and didn’t want to necessarily go back to the fields. He yearned to get back to the big city.

Teeta couldn’t remember exactly what Weesie had looked like, only that there was a buttered-cornbread-colored young woman who always bought two collard bunches and one mustard, and took her time picking through the largest and roundest sweet potatoes. When he finally wandered his way back to Columbia, every Saturday he’d roll off his army brother’s mother’s couch and say he was going to work. It was something like work. He would go and help the elderly carry a week’s worth of fresh vegetables to their trunks and get a few coins in thanks. He would walk up the road to the Winn-Dixie and offer to help bale the empty vegetable boxes, sweep—anything. Sure, he was getting whatever thanks the service offered for years of his life and pieces of his brain—and he gave up most of that for his share of the rent, for a few cans of Schlitz or Olde English, his ration of Marlboro cigarettes from the Shamrock Corner Store, and a few rounds of pool at night. It was when that routine got old and folks kept asking when he would settle down that he remembered the woman he had wanted to get to know before he was sent off to the war. Just when he had gotten the nerve to ask her to go steady, he turned eighteen and immediately was served papers. He figured it won’t no use starting something only to go off and die in Korea and leave her broken.