Excerpt

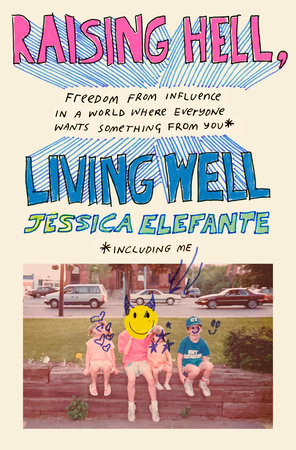

Raising Hell, Living Well

TRACKS (or Our Inner World: Influence Below the Surface, the Direction It’s Pointing Us, & Aspiring to Cross It)

Upstate New York is the bologna sandwich of New York State.

Utica, New York, specifically, is something of a caricature—the satirical target of American cultural cornerstones from

The Office to

The Simpsons, in which Homer famously said that the area could “never decline because it was never that great.” It’s a late show punch line, roasted by hosts. It’s objectively outdated in its architecture, infrastructure, and industry, but also at times, in its beliefs and worldview. It’s like that uncle who’s just a little bit inappropriate, but he’s from another time and mostly means well, so you try to let it slide and love him anyway.

Some would call it a joke. I call it home.

Having been raised in the heart of that Wonder Bread sandwich, I am forever both defending and judging my roots. But in reality, it’s that polarization that created the foundation of who I am and how I approach the world. I am that tension. After all, the influence of where we begin can determine a lot about where we end up.

Borders, zip codes, tracks. Wrong side. Right side. These are among our very first influences that blend beneath the surface of “us.” Let me show you what I mean.

When the railway was first invented, neighborhoods near or downwind of the tracks bore the brunt of noise and soot from the locomotives. Naturally, those areas quickly gained a reputation for being socially inferior. Literally and figuratively, the tracks divided the more prosperous from the poorer. They separated those with good fortune from those who drew short straws. Ever since, tracks have represented a not so invisible line. They are the straight of an arrow pointing in the wrong or right direction, depending on which side you are on, and a reminder of a possible way out if you could only follow the wooden planks beyond their known world. As a little kid, I crossed over the tracks on yellow school bus number 223. When that bus bumped over those tracks, my three siblings and I would lift our feet, cross our fingers, and hold our collective breath, making wishes for good luck. For me, the tracks were everything. They represented the ways in which I didn’t have enough and the ways in which I had more than many. They were my escape route and—to this day—my path home to myself.

Utica itself exists as a kind of “other side of the tracks” to its more well-known and well-loved counterpart, New York City. Or at least that’s how the people who live in Utica feel. In reality, most New Yorkers have barely heard of it. The competition is one-sided, an inferiority complex well earned.

It’s also a mishmash of commingling opposites from opposing sides of the tracks—old and new, rich and poor, Black and white, educated and uneducated, red and blue. Our small footprint is home to a whopping seven universities and colleges, but also faces an intense brain drain when so many of our educated young adults flee after graduation. We have ostentatious McMansions built on tall bucolic hills overlooking valleys with jails on the other side of them. We have a diverse mix of ethnicities and races, but segregated towns. We have centrists and apolitical types—not to be confused with the liberal hippie havens of downstate. And moderate is about as progressive as the majority of people get, living next door to secretly staunch Reagan-era Republicans and die-hard Trumpers. And it’s been a place throughout history for immigrants to start over. But when Utica more recently opened its arms to refugees—in the ’90s to Bosnians following the Bosnian War, in the early aughts to Burmese Buddhist monks after the Saffron Revolution, and, as recently as 2021, to Afghans after the fall of Kabul—it was often the second- and third-generation descendants of immigrants who resisted “those people” coming to “their city” to “steal” their jobs. It was as if they’d forgotten that their families were once from somewhere else too.

I was made there, born to an Irish mother from the “right side” and an Italian father from the “wrong side.” So maybe it makes sense that even my immediate family was rife with contradictions: I was raised to believe there was never enough and always enough at the same time. I was taught to respect authority while also to challenge it. I was sent to a religious school by an at-the-time agnostic father and a now-repentant Catholic school girl who never lost her faith in God but did the church. While conservatism was historically our family’s brand, the beliefs of the household were mostly liberal. I was a “free lunch” kid at the local suburban rich school, hiding my dime stipend below the milk jug. And maybe because of all of that, I was the first kid in the family to gain admission to a fancy liberal arts college—and the first to toss it aside in search of something more. Influence is wily that way.

My parents—who divorced when I was thirteen—will each tell you that their side of my heritage is the better half. Family mythology, spun into lore around our kitchen table, told us that the mix of our genetics—Irish and Italian blood—made for beautiful children with bad tempers and, later, drinking problems. It’s this sort of objective bravado that defines the people from my hometown—slightly self-aware, deeply self-deprecating, and unbelievably stubborn. At once, celebratory and dejected. In my experience, that cocktail makes for really fun, warm people with an edge, great conversationalists full of spirited ribbing and quick wit—but only if they like you. The people have big hearts but also hard noses and chipped shoulders. And it’s one of the reasons I think I’ve tried, and failed, to live happily in many other places. When sarcasm and grit is such an part of your inner makeup—a love language of sorts—those characteristics make it difficult to connect with people who would happily trade irony for a balmy 72-degree, sunny existence. That’s just not the Utican way.

Known as the original Sin City thanks to its history of organized crime and political corruption, my family lineage reflects that in spades. Putting Utica on the proverbial map was a great, great uncle from my mother’s side who was the vice president of the United States under Taft. But it was a more questionable relation—a distant great-uncle on my father’s side who was the proverbial backroom political boss of Utica who took it off. I have experiences of baby grand pianos, afternoon patio cocktails, three-piece suits with bow ties, and Cadillacs. And memories of backyard tin can tomato plants and plastic-covered sofas, dingy bars, old cars, and even older card sharks. Just the right amount of high/low to help me develop “character.”

My hometown is chock-full of upbringings that molded beautiful humans, but also created odd friction. People love it and love to hate on it. Utica is equal parts charming and befuddling hot mess.

At times, you could describe me that way too. It’s not surprising. After all, our origin is one of the greatest influences on us—where our ancestors hail from, where we are raised, where we choose to live, and even where we fall within our family order—origin sets us on a track from which it is hard to veer. Place shapes us. The influence of these chance factors, some fixed and some not so much, is incredibly formative, affecting our Inner World from a young age. For the lucky, this means being born with a horseshoe up one’s ass; for the ill-fated, it’s bad trot.

The first time I got drunk was on some still-functioning but old railroad tracks. They were situated next to the local strip mall at the bottom of McMansion hill. Next door was the police precinct, which should have made it a dicey spot for underage alcohol consumption. And yet, there we sat. In the glow from the parking lot’s single light, my best friend Roxanne and I could see each other’s shadowed thirteen-year-old faces, my apprehensive expression reflected in her Coke-bottle glasses. At the time, I was a somewhat naive rule follower because I hated to get in trouble and had no older siblings to show me the ropes. Also, my parents’ child-rearing philosophy for me, their firstborn, could be summed up as high expectations for everything, low tolerance for bullshit. As is often the case with parenting strategies, this philosophy waned as the years passed and the number of children grew. For my three younger siblings, tolerance for bullshit went way up. I’m still a little bitter about the long-lasting, somewhat unshakable influence of our birth orders. But in the meantime, my friend Roxanne was my “bad influence,” an only child who never really got in trouble and whose father, Tony, doled out twenty-dollar bills from a rubber-banded wad of cash. We were just entering teendom. Yet in the stones and dirt on the railroad ties, Roxanne and I sat, mixing room-temperature vodka stolen from my pop’s liquor closet with too little gas station OJ. Things were headed in a poor direction.

Being on the tracks, as Roxanne and I were on that night, was in some ways preferable to being on either side of them. During my childhood, I had a clear sense of existing just barely on the right side.