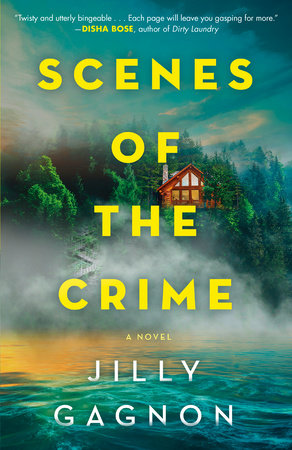

Excerpt

Scenes of the Crime

1I’d made it about thirty percent of the way through the most glaringly inane round of script notes known to man when a ghost walked into the coffee shop.

Actually, let’s back up about five minutes. As a screenwriter, I should know to set the scene at least slightly.

I closed my eyes, breathing deeply in through my nose, out slowly through my mouth, trying to let the white noise of the coffee shop fall away, let my mind go blank, keep my focus on the breath moving through my body, all the way down to my fingertips, weaving through my leg muscles on its way to the soles of my feet, slithering along my vertebrae and pooling in my tailbone, whispering up into the tips of my eyelashes. Calm. Lower your vibrations and be calm.

It would be weird anywhere but LA.

But eventually I had to open my eyes again, and that same idiotic script note was still staring back at me, maddening in its Feedback 101 simplicity.

Motivation? Why is she still here? Let’s dig deeper.

She’s still here because this is an episode of Back of House, the broadest of network comedies, a slurry of gender stereotypes, cheap sight gags, and plotlines so dull they couldn’t even cut the mental mashed potatoes we’ve been serving up for five seasons now, Mike. She’s here because the loving but slightly exasperated wife character—literally, in early versions of the pilot her name was Wife—exists exclusively as an eye-rolling sounding board to her husband’s constant string of wacky mishaps in the restaurant they run together.

And not for nothing, you don’t need motivation to stay when the A story for the episode is “Hector accidentally locks himself and Maria into the staff bathroom before an all-important VIP dinner. But Maria’s new get-fit focus on hydration means soon she’s gonna have to go . . . when neither of them can go anywhere!”

I could feel a thin layer of my molars sanding away as I tried to cling to those “breathe deep” vibes. Useless. Say goodbye to your enamel, Emily.

I reached for my brownie, breaking off a large corner and stuffing it into my mouth as I sank into the too-deep armchair I’d set up in for the day, letting the chocolatey goodness do what meditative exercises alone couldn’t manage. I looked out over the coffee shop, my favorite in LA not only because it was walking distance from my Los Feliz condo, but because the dim, windowless, sagging-velvet-upholstered-furniture ambiance seemed to scare off some of the would-be actors perpetually posing for the candid shots no one was taking of them. Instead, it attracted my people: the huddled screenwriters actually eating the indulgent baked goods, the blue-light glow of their screens only highlighting the vampiric pallor, unkempt hair, and smudged eyeglasses that formed their personal rebuttals to the famous promise of carefree SoCal sunshine. I always came to Grandeur in Exile when it was my week to write the script. It was impossible not to get work done surrounded by so much hushed intensity.

And occasionally, like now, someone so unexpected would appear that it revived that tiny flame deep inside me—perilously close to snuffing out after five years in the Back of House writers’ room—that flickered with What’s that abouts? and Wait, reallys? and in this particular case, a What’s she doing in here? The tiny moment of not-quite-rightness that feels pregnant with an untold story.

The woman at the counter had the elongated proportions of a designer’s sketch, all willowy limbs and swanlike neck, its slim length accentuated by the sharp line of her near-black bob. Even I could tell that her outfit—trendy black booties and a long-sleeved raw silk sheath, the demure hemline seemingly contradicted by the way it clung to her slim figure, highlighting every curve—was expensive, in a Beverly Hills way you rarely saw in this part of town. And she was carrying a fricking Birkin. What was someone like that doing in this dungeon—albeit a dungeon with plush amenities and excellent wifi—for creatives?

And then she turned to glance toward the heavily curtained windows and I almost choked to death on gooey chocolate.

It was Vanessa. But it couldn’t be.

Vanessa had been gone for fifteen years. I should know. I was one of the last people to see her alive.

And it was possible I was the one who had killed her.