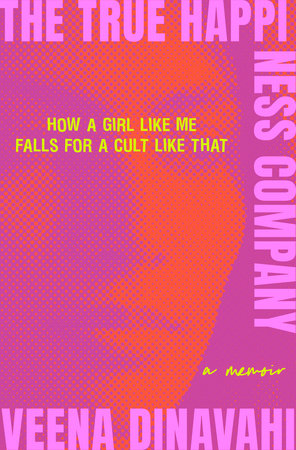

Excerpt

The True Happiness Company

1June 2011I didn’t know what to expect from the True Happiness Company—crystal healing? bloodletting?—but I didn’t expect Bob Lyon.

Amma first found Bob on one of her infamous late-night Google searches. Amma—my very sweet, very bright former cancer research scientist mother—has two master’s degrees, in biochemistry and biotechnology. She also once nearly accepted a job scooping eyeballs out of dead bodies, despite the fact that she faints at the sight of blood. People think it’s easy to know yourself, your boundaries and fears and limits, but decision-making is a convoluted process. Necessity has a way of overpowering all other considerations. A frequenter of Tony Robbins seminars and an inspirational speech addict, Amma has a long-standing history of finding sketchy people on the Internet and paying them too much money to do whatever they promise to do: turn our sad, dying lawn into a lush blanket of green, teach her how to get rich quick in the stock market or, in this case, save her daughter’s life.

She called Bob on her way to work.

“Pull over,” he instructed. “Pull over right now.”

Alarmed, Amma pulled over on a side street of Baltimore.

“If you do not bring your daughter here, she WILL be dead.”

It is one thing to have a worst fear nebulously haunt the back of your mind and quite another to hear it pronounced as an inevitability by a strong, commanding voice who has published more than a dozen books and hosted seminars worldwide. Emails were exchanged. An appointment was made.

I didn’t know it at the time, but Amma hadn’t found Bob’s website on her own; she’d first found a blog written by a woman whose son had been suicidal. Amma called her, and the woman said, “Take your daughter to see Bob Lyon now.”

If you are a parent, if you have ever been confused and desperate and aching for your children, then you know the tug of a fellow mother’s heartfelt advice. Amma made all her parenting decisions based on these kinds of recommendations; I ended up playing the violin because she sat next to a woman at my first orchestra concert who insisted that once you allow a child to quit one thing, they become a quitter for the rest of their lives. I was in the third grade and spent the next ten years taking private violin lessons in the home of a woman who collected hot sauce and owned eight cats. Shelves and shelves of hot sauce filled the entryway, the living room where I had my lessons, and the kitchen, of course. This teacher fed squirrels out of her hand on her back porch during my lesson while I dreamed of playing the flute. When I asked Amma years later why I hadn’t been allowed to switch, she shrugged and answered, “I sat next to this woman who said . . .”

If the confident word of a stranger could dictate what instrument I played, imagine how much more weight it carried when Amma was faced with a suicidal daughter she could not seem to save.

The first thing I said to Bob Lyon was, “I don’t have to do shit,” as I flounced into the soft corner creases of a once-white couch in his living room.

At least, that is his version of our first meeting: me waltzing into his home in back-country Georgia and cursing before he can get a word in edgewise. Though I’m certain he spoke first, I’ve since forgotten what he said that put me on the defensive. At age nineteen, I didn’t typically curse at adults—part of that Indian “respect your elders” thing—plus cursing tended to go over poorly. But Bob Lyon was unperturbed.

“No,” he said. “You really don’t.”

I flinched. His response was disconcerting because he was the first adult I’d met who I couldn’t unnerve. Had he not spoken first? Was I making it up? Was I the kind of person who dropped expletives unprovoked? This feeling of disorientation—this constant second-guessing of myself—pervaded our entire relationship. My memory buckled under the force of his confidence.

Bob Lyon looked like a giant, unamused teddy bear when I showed up in his living room that day. “Living room” was a misnomer: nothing about that room inspired the will to live. Instead of the framed diplomas you’d find on the walls of a typical psychologist’s office, his walls boasted gold-framed animal prints—one of a Siamese cat and another of two intertwined peacocks. The two couches formed an L shape facing the center of the room. A plastic chandelier was fixed to a stippled ceiling overlooked by the past two decades of decorating trends. To my left sat a textured gold floor lamp that looked like it worked weekends at the Olive Garden. A tiny statue of Jesus on his fireplace was the only indication that he was Mormon—but I wouldn’t learn of this fact for another four years.

In the center of the room sat Bob, this big, old white man in a rocking chair. The chair was wooden, the kind you’d expect to find on a wraparound porch with Buffalo Bill kicking up his cowboy boots, resting a rifle on his lap. Bob wore an untucked plaid shirt and blue jeans. He wore no shoes, just thick, white socks. My first impression of him was “redneck.” This is also my final impression, though my feelings toward him have taken a wild detour to arrive back where they started.

“You’re right. You don’t have to do anything. But,” he said lightly, “I know something you don’t.”

“Okay.” I knew I was being set up. Still, I wanted to get to the punch line more than I wanted to fight. “What?” I conceded.

His eyes bored into me with such intensity that I felt like I’d been caught naked on the shoulder of the expressway. I wet my lips and averted my eyes.

“I know how to be happy.” He spoke quietly now. “Look, kid, you’re stuck here for three days. Your parents won’t let you leave. You’re welcome to go back downstairs and watch TV. Or go outside and walk the grounds. We’ve got some nice woods out here and a lake behind the house. But you are so miserable that your life couldn’t possibly get any worse. You’ve got absolutely nothing to lose.”

That was it. His big pitch. Looking back, I did have things to lose: my agency, my values, the sanctity of my body. How could I have known that a shot at his version of happiness meant trading it all in?

In the eight years that I was in his orbit, he would recount this story of how we met so many times, to so many different people, that it became canon in the True Happiness community. He’d emphasize how I “flounced” to convey my spunk and how much he liked it: She didn’t just sit, she flounced. He’d flick his wrists to illustrate my miniskirt bouncing onto the pleather surface of his couch. Then he’d point to the corner where I sat. Here, he’d interrupt himself to observe how he remembered exactly where everyone had sat the first time they’d met him. He always phrased it that way: they met him. There was an air of immutability and pleasant anticipation in his telling. The meeting of two great minds.

But very different feelings pervade my memory of our first meeting. Anger, as I climbed into the back of my mom’s minivan in our Maryland suburb. Resentment, as the ride progressed, and I approximated how far south we had traveled by averaging the number of Cracker Barrel signs on the roadside. Fear, as we pulled into a nondescript driveway in the middle of nowhere at midnight. Disbelief, as my mom fished a crumpled piece of paper out of her handbag and smoothed it against the dash, insisting she had instructions to “follow the lighted stairs to the basement guest quarters.” Unease, as I watched my parents disembark and do as they were told.

I did not choose to be in his living room, but choices become limited when you have spent the past three and a half years sort of trying to die. There is some debate over whether my actions were suicide attempts or suicidal gestures. I am unclear on the distinction here. All I can tell you is that killing yourself is harder than it sounds. Between the ages of fifteen and nineteen, I swallowed pills over and over. I drank ant poison (doesn’t work on mammals). I tried to hang myself but didn’t know how to secure the rope to the ceiling.

Living is hard and dying is harder.