Excerpt

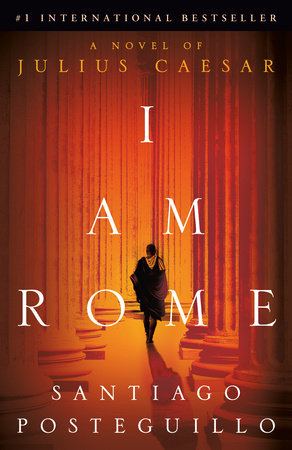

I Am Rome

Prooemium The Western Mediterranean

Centuries II and I B.C. Rome’s growth is unstoppable.

Since the fall of the Carthaginian Empire, Rome has become the dominant power in the Western Mediterranean region. Already controlling Hispania, Sicily, Sardinia, Italy, and parts of northern Africa, it has begun to set its sights farther, on Cisalpine Gaul, the Celtic lands north of Italy, and Greece and Macedonia to the east.

Rome’s expansion has filled the republic’s coffers to the brim, but the distribution of wealth and conquered lands is far from equal. A small group of aristocratic senators accumulates ever more territory, ever more riches, while the vast majority of those governed by Rome remain deeply impoverished. All confiscated lands, gold, silver, and slaves are controlled by a few landowning senators from patrician families.

Such blatant inequality leads to conflict: the Assembly of the Roman People demands a more equal allotment of wealth and power. A few bold men speak out in favor of redistribution. Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus is among them. Son of famed Roman mother Cornelia and grandson of the great statesman Scipio Africanus, he is chosen as plebeian tribune, the people’s highest representative, and sponsors a law of land redistribution in the year 133 B.C. But the Senate ambushes him on one of the city’s main thoroughfares, beating him to death in broad daylight and tossing his body into the Tiber, without a proper burial. His brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, is later elected plebeian tribune and attempts to further Tiberius’s reforms. In response, the Senate passes an unprecedented decree granting the Roman consuls, top leaders of the Senate, the authority to detain and execute Gaius Gracchus or any other plebeian tribune who supports the redistribution of lands. In 121 B.C., finding himself surrounded by the Senate’s assassins, Gaius Gracchus asks a slave to kill him so that he does not fall into his enemies’ hands.

Supporters of the Gracchi brothers and their thwarted attempts at reform join forces to create a group that calls itself the populares, “in defense of the people.” The more conservative senators, in turn, form the party of the optimates, meaning “the best,” since they consider themselves to be superior and favored by the gods. Rome is officially divided into two opposing political factions when a third group emerges. The socii, inhabitants of Rome’s allied cities in broader Italy, demand Roman citizenship and the right to vote so that they might take part in decisions that affect them directly.

The Assembly of the Roman People, time and again, elects new plebeian tribunes who, over and over, try to pass reforms like those initiated by the Gracchi years prior. All of them are systematically killed by the optimate senators. Finally, a young Roman appears, patrician by birth but sympathetic to the demands of the populares and the socii. He understands that a fourth group has entered the fray: the inhabitants of the new Roman provinces that have been annexed from Hispania to Greece and Macedonia, from the Alps to Africa.

This young man believes that it is time for things to change once and for all, but he is only twenty-three years old, with few supporters. In fact, hardly anyone in Rome has even taken notice of him. That is, until a trial in the year 77 B.C. when this man, despite his youth, agrees to prosecute a powerful senator.

The defendant, accused of corruption during his term as governor of Macedonia, is none other than optimate senator Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella, who amassed unthinkable wealth and power as a close ally to the tyrannical Lucius Cornelius Sulla, former dictator of Rome.

Sulla, during his dictatorship, decreed that senators could only be tried by a jury of their peers: other senators. This means that the tribunal set to hear Dolabella’s case is composed entirely of optimates and is expected to fully exonerate Dolabella, who has also hired the two best defense attorneys in Rome: Hortensius and Aurelius Cotta. Seeing the case as a lost cause, no Roman lawyer will agree to prosecute Dolabella. Only a madman or a fool would bring charges against such a powerful senator under such disadvantageous circumstances.

Until one man finally steps forward. Dolabella laughs when they tell him who has agreed to serve as prosecutor in the trial against him. He continues his endless series of parties and banquets, secure in the notion that his case has already been won.

The name of the inexperienced young lawyer who agrees to prosecute him is Gaius Julius Caesar.