Excerpt

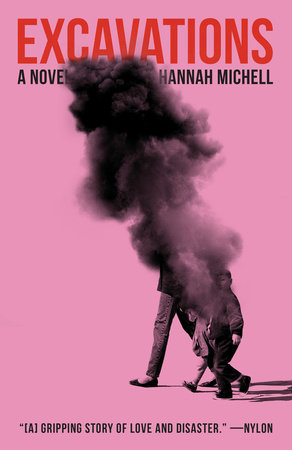

Excavations

Collapse

1992 Jae was a man of his word, and he had promised Sae he would be home at six o’clock. Sae glanced at the green cuckoo clock in their kitchen, waiting to see the small bird pop out to announce the hour. The last half hour before he returned every evening was the hardest. It was so close to the end and yet still so much in the thick of waiting. The children were growing tired, their careless movements more and more wild in their too-small apartment.

She imagined Jae crossing the barricades, about to board the subway, moving toward them. Hours earlier, when she was reunited with her children, she had been delighted to see them. Pausing at the preschool gates, she watched them basking in the schoolyard, unaware of her watching them. Then there was the moment she loved the most—when they noticed her and let out squeals of delight before giddily jumping into her arms.

She could not get used to being called someone’s mother, the way it erased her name, made her a stranger to herself. Yet in these moments of reunion when her younger son, Hoon-min, clung to her, she felt alive and powerful—a captain rescuing those from a sinking ship—a feeling that lasted only for a while before her nerves started to fray in the unspooling hours and she began eyeing the clock for their father’s return.

The boys were hungry, but she wanted to wait for Jae. For weeks his work as an engineer at Aspiration Tower had been keeping him on-site at all hours. Tonight, he had promised to come home early so they could eat together, though by six-fifteen there was no sign of him. She was like an overfilled kettle, and Hoon-min’s whining was the flame threatening to boil her over. Having checked that the boys had not unplugged the phone from the wall again, Sae looked at her silent pager, feeling herself begin to rattle with fury. Shouting for the boys to sit at the table, she prepared rice and seaweed, shrugging off the guilt of offering them such a paltry meal. It’s not as though we do this every day, Jae would say. He knew exactly how to defuse her. She felt herself soften toward him, so she willed herself to stay angry.

By seven o’clock, Sae had no choice but to surrender to Jae’s absence. She considered leaving him a message on his pager, but he would call soon, she thought, with an excuse about being tied up at the Tower. Taking command of the evening, she started a bath, instructing the boys to stop touching each other’s penises, to stop splashing water at her or in the other’s eyes. They ignored these instructions. Seung-min wanted to get out; he was too warm, he said. Hoon-min wanted to stay in. She took a deep breath, her patience flickering like a weak flame. She sat on a low pink stool with her back against the wet tiles as they splashed around. When she could no longer ignore the ache in her back, she announced that it was time to get out, only to be ignored again.

“Listen!” she hissed. “Out!”

The knife’s edge in her voice froze them instantly. Obediently stepping out of the bath, they stared at her, wide-eyed. Sae turned from them, already sorry. She hated destroying their spirits, but she felt extinguished and they needed to be in bed.

“Where’s Appa?”

“I don’t know.”

“I want Appa.”

Hoon-min began wailing. Seung-min ran out, leaving a wet trail behind him as he leapt on the bedding on the floor. Dressing the boys quickly, she turned off the light, threatening to leave them to fall asleep alone if they didn’t calm down. The words had the desired effect. They both fell onto the bedding as if wounded, and Sae got down to lie between them. They writhed, tossed, and fidgeted in the heat. The boys gripped her earlobes. She was their jungle gym, their plaything, their anchor. Hoon-min’s hand grew heavy as he rolled over and yawned, sleepily tugging at her T-shirt. At two years old, he was still in the habit of nursing himself to sleep, but she had resolved to wean him. She held his hand and squeezed it. No. Seung-min’s breathing changed, calmed, but his eyes remained open at some fixed point on the cracked ceiling.

Hearing a noise outside, Sae held her breath, fearing Jae had chosen this very moment to come home. All her hard work to calm them would be undone if the boys saw their father. But moments passed. There were no creeping steps, only the sounds of the whirring, aging refrigerator in the kitchen, the low white noise of distant traffic on the freeway, the boys’ rhythmic breathing. They had finally stopped squirming, their long eyelashes lay still. How beautiful and miraculous they were in the darkness, with sleep between them. The first thing Jae did when he came home late was to look in on the boys, huddled together in their slumber, like a thief reassuring himself of the safety of stolen jewels. She loved that he never took them for granted, that he did not share in her ambivalence spending hours loving them and longing to be apart from them, to be distant and present at once. She wanted them to grow up, she wanted them to stay small. Jae’s devotion was a source of wholesomeness in their relationship, but in his treasuring of them she also saw a specter of a childhood spent wanting—for him family was an elusive thing—a fish slipping out of his grasp.

Stillness did not suit the boys. Sae felt an anxious tangle in her stomach. A premonition, perhaps. She left the room to resist the impulse to wake them. As she lit a green coil to ward off mosquitos, the anger she had felt slid into worry. It was eight-thirty. She paged Jae. It wasn’t like him not to call. All day the air had held in its fist the threat of an unforgiving summer. Soon the monsoon season would arrive, bringing with it the unwelcome lodger, a humid creature who would come to live in their books and bedding, clothes, and cushions. There was glory in the stickiness; the way it invited them to peel off their layers, soaking in the humid evening heat, unable to sleep, suddenly open to each other. He had never been a man of many words, but for months Jae had seemed preoccupied and distant, troubled by his project at Aspiration Tower, and was even quieter than usual. Then recently, a series of power cuts had seized the city and in the evenings, when there was no light to work, they had taken to sitting on the balcony, passing a can of cold beer between them, and she had felt him return to her.

Sae stepped out onto the balcony, looking at Jae’s empty seat. The countless windows of the apartments in the block facing hers appeared to her as a stack of miniature screens projecting similar lives. These glimpses were the closest thing she had to the interviews that she had conducted for work—when she’d gathered tumultuous accounts of life under dictatorship. She missed the pace of working at the newspaper, feeling the pulse and beat of breaking stories, but there was a reassuring comfort, too, in the ordinariness of her days at home with the boys.

She was pulled from these thoughts by the ring of the phone, and she picked up immediately, afraid the sound would wake the boys.

But it wasn’t Jae. It was Bo-ra—who lived in the apartment two floors above her.

“Just checking in, making sure Jae got home all right. You said he was coming home early,” she said. Sae could hear that she had food in her mouth and frowned, struck by the formality of a phone call.

“What do you mean?”

She heard the twist of the phone cord. Bo-ra’s voice was suddenly a little louder in her ear. “He has come home, hasn’t he?”

“No, he’s late, actually . . .”

There was a pause. Bo-ra’s voice had a strange quality to it when she spoke again. “Turn on the TV,” she said and then, quietly, “It’s all over the news.”

The TV flickered to show the image of a car turned upside down on a street that was littered with debris. Uniformed workers were stepping over glass, their hands over their mouths. The camera panned out to display rising plumes of dust and smoke.

A bespeckled interviewer held his mic to a man who wore a suit covered in dust.

There was a loud boom, and the middle of the building just came down. I’ve never seen anything like it. I knew I had to get out when I first heard the noises. It was like some strange groaning animal. But there are others, he stammered, wiping the sweat from his face with his hand. There are still people trapped there.

The room began to sway, and she gripped the side of the TV stand with both hands. The phone receiver slipped onto her shoulder and she had the sensation of shifting pressure in her ears, distorting all sound. Bo-ra’s voice sounded distant.

“Have you heard from him?”

Sae jerked her head to her shoulder to stop the phone from falling and pressed it against her ear.

“That’s not . . . it’s not . . .” Sae could not quite bring herself to say it out loud. Aspiration Tower. “When did this happen?”