Excerpt

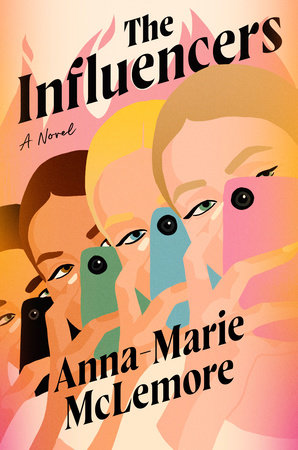

The Influencers

we the followers of Mother May IWhen the news first broke, everyone wondered: Who was May Iverson? And why did she look so familiar?

But we already knew her. We’d been watching her for years.

Mother May I’s very first post had been almost twenty-five years ago, on a platform that didn’t even exist anymore. She’d started with tricks for bad hair days, the fastest way to frost a cake, last-minute Halloween costumes, stunning table decor from things you probably already had around your house. May Iverson, the woman behind Mother May I, was a mom of three, and then four, and then five daughters (at the time of that first post, the eldest, April, was four, twins June and July had barely started walking, and January and March would be born over the next couple of years).

May Iverson was both maddeningly glamorous (how were her nails never chipped?) and relentlessly encouraging. She reminded us all that we were doing the best we could. She told any of us who needed to hear it, “You are a good mom. And all this is optional. Your kids’ happiness doesn’t depend on a wire-ribbon bow. This is all for fun. Remember, you’re already a good mom.” That became her reassuring catchphrase at the end of every video. Remember, you are already a good mom.

As her following grew, so did her ad revenue and her rate for sponsored content to show off a new planner or setting powder. Mother May I would tell us about the lipstick that stayed all day so a busy mom didn’t have to reapply, as though she was sharing a secret with a friend. She’d detail the benefits of the meal-kit service that made her evenings “just so much more relaxing. This has turned my routine into a gourmet ritual.” Until she was, increasingly, making her living by telling us how to live.

Cosmetic companies sent her KitchenAid stand mixers in the latest colors, ostensibly as birthday (and later, wedding shower) gifts, but more likely so she’d give their new bronzer a good review instead of saying that it skipped on application. Designers delivered free gowns and jewelry for fundraisers, hoping she’d show them off in front of the step and repeat. A fragrance line made a perfume bearing her name, pennies’ worth of ester chemicals in a fancy bottle, surrounded in the ad by flowers and billowing fabric.

In two and a half decades, May Iverson had turned herself into a name that drew both sneers and aspirational sighs. She had turned her content into an empire, complete with makeup, swimsuit, and kitchenware collaborations. She had—thanks to the work of surgeons, aestheticians, coaches, and trainers—kept her fifty-three-year-old face and body looking so astonishingly young that no one could believe her eldest daughter was now twenty-nine.

A lot of us thought she’d changed in the past five, seven, maybe even ten years, and not in a good way. It didn’t ring true anymore, her still giving tutorials on the flood-iced cookies she used to make for school bake sales. It wasn’t just that her children were all adults, all in their twenties, long gone from the world of locker-room linoleum and PTA fundraisers. It was that the designer bag on her kitchen counter declared she could have just as easily bought immaculately frosted cookies, or made a donation.

She made stabbing tries at being relatable by talking about the puffiness under her eyes, and then showed off tricks with spoons chilled in the refrigerator, even though she could afford weekly facials and frequent microneedling. She relayed her favorite ways to mix and dilute essential oils, even though we all knew she had home fragrances blended especially for her by a famous parfumier in Lyon.

She said she never dieted—“it’s more about being in harmony with your body, listening to your body, loving your body”—but then did sponsored posts for appetite-suppressing tea. The few times she cried genuinely on camera threw into harsh relief how different it looked from when she faked it, and how often she had. There was the time she complained about caterers not bringing out micro-batch cheeses early enough, so they didn’t soften properly by the time her first guests arrived. Even those of us who still adored her cringed remembering her post about how so many designer boutiques didn’t carry heels in a size as small as hers, that they had to special-order them. She said this shyly—“I’m not even short, I don’t know how I ended up with such small feet”—though with a smile she couldn’t quite contain, like a humble-bragging Cinderella.

But when it came down to it, she didn’t need anyone’s forgiveness for being fake. She knew what she was doing, and so did we. With every display of metallic-painted Halloween pumpkins, with every holiday ribbon adorning the banisters of her mansion, with every time she documented getting one of her daughters ready for a ballet recital, lipsticks and juice boxes spilled across her vanity, she was producing a specific version of herself. May Iverson was constructing Mother May I. And we watched because, whether we admitted it or not, we wanted to know how to do the same thing.

It wasn’t so much that we all wanted to sew our children one-of-a-kind tutus, or make grocery lists so ornately decorated that they could have gone into scrapbooks. Sure, some of us did. But most of the time, it was far simpler than that.

Life requires artful lying. It just does. You have to tell your husband how much you loved catching up with his mother. On a bad morning, you put on a little extra blush to make yourself look less miserable than you are. You run into someone from the gym you haven’t gone to in months and tell them you’ve switched to a 5 a.m. workout, that must be why you keep missing each other.

You get coffee with a friend you haven’t seen since elementary school, suddenly realize you have nothing in common, that every minute together feels stilted without the mortar of jump ropes and sticker trading. But when both your cups are empty, you still have to say We should do this again soon or Let’s not let so much time pass next time. And you hope she is lying just as much as you are, because if you have to do this again, you might need defibrillating levels of espresso or to snort lines of sucralose off the café table.

May Iverson was good at fake. She made fake look good. And whether we admitted it or not, we watched to learn. We wanted to learn how to lie and make it look that pretty.

June Iverson

Guess he finally pissed off the wrong person.

The words were almost out of June’s mouth.

Then June read the room. Or rather, the only other person in it.

July sat on the edge of the distressed vegan leather sofa, almost crying but not crying, facing the TV but not really watching it anymore.

August was dead. And the neighbors were all sniffling on TV, pretending to be surprised. Were they f***ing kidding? August had screwed a lot of people out of a lot of money, often with nothing but the twist of a contract clause. Former partners. Investors. Men who were basically loan sharks in Givenchy. What did he think was gonna happen? Seriously, white guys with eight-packs thought they could get away with anything.

But her poor mother. August had been the one making bad decisions, yet it was her mom’s house that got torched. It would probably be five years and fifty thousand dollars in therapy before Mom realized this was a blessing in disguise. Whatever six-pack sorcery August had cast on her mother (Who had he been trying to fool? He’d never had an eight-pack in life or in death), it would take some concerted deprogramming to get her mom back to normal.

June decided right then that she and July would take their mom out of town. Tomorrow. That new spa in Sedona. Red rocks, turquoise pools, desert air purified by cactuses. If their poor mother was going to cry on a bathroom floor, it might as well be manganese Saltillo tile.

July was wrapping her arms around herself, palms on her goosebumped elbows, as the sound and the light of the broadcast washed over her.

“If you’re cold, put on a sweater,” June said, and she knew as soon as she said it that she sounded like a bitch. So to make up for it she pulled a peacock-blue cardigan from July’s sweater shelf and threw it at her.

Then June called their mother. No texts. Not right now. Nothing written down.

June was always the one calling their mother, putting the phone on speaker for both her and July. Even on the best day, July was tragically timid about bothering their mother, like she was an interruption as unwelcome as an underpaid sponsorship opportunity. Plus, July was constantly losing her phone under the five thousand pets that lived in this loft with them. The dogs flopped on it without noticing, and the cats curled up on it like it was a heating pad. Once, Buttons the rabbit had tried to chew on it but had quickly lost interest, luckily for both Buttons and the phone warranty.

Their mother didn’t pick up.