Excerpt

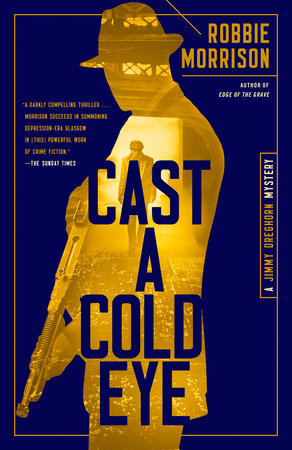

Cast a Cold Eye

1 Glasgow, Wednesday, 29 March 1933 In the countryside, or far out at sea, the water was no doubt clean and fresh, but when it reached the city it was as dark as sin, punctuated occasionally by cheerful rainbow swirls of oil, leaked from the battered boats that plied their trade on the canal.

Inspector Jimmy Dreghorn stopped at the lock gates, glanced one way and then the other. A couple of weans were walking a dog on the opposite side of the canal. One of them threw a stick and the mutt followed fearlessly, launching itself into the water despite the icy temperature, springtime or not.

Dreghorn looked at Police Constable Ellen Duncan, who pointed west, in the direction of the Kelvin Aqueduct, where the canal crossed over the River Kelvin.

“Just along there’s where everyone goes winching, sir,” she said authoritatively. “Or at least, they used to.”

“Notice I don’t ask how you know that, constable.”

She gave him a cheeky, knowing look. “Please, I wasn’t always a—”

“Fine upstanding member of society?” Dreghorn interrupted.

“Police constable.” She spoke over him. “And I do have a life off duty, you know.”

Dreghorn raised his hands. “Whoa, I’m scandalized enough already.”

The Forth and Clyde Canal cut across the Central Lowlands, joining the two Scottish coastlines, from the Firth of Forth at Grangemouth in the east to the Clyde at Bowling in the west, both rivers then leading out to open sea. When first opened in 1790, business was booming, with timber, oil, and coal transported from one side of the country to the other. Barges and other working craft bobbed happily alongside yachts and pleasure boats, an unlikely camaraderie between the classes as they navigated the locks and sluice gates.

As the influence of the railways grew, transporting greater quantities of freight more swiftly, and the trend in shipbuilding veered toward vessels too large for canals, the Forth and Clyde had fallen into decline, not helped by the Depression, which had engulfed the country four years earlier.

A lumber boat was approaching the lock, heading west toward Bowling, and the lock-keeper emerged reluctantly from his cottage to assist at the gate, breath misting in annoyance as he buttoned up his overcoat. He saw the dog swimming toward the stick, right in front of the boat.

“Get that dug oot my river,” he yelled, “or I’ll chuck you in after it!”

He spotted Dreghorn and Ellen, straightened his cap, and asked suspiciously if there was anything he could do for them.

“Aye,” Dreghorn growled, “don’t draw attention to us.”

They walked in the direction Ellen had indicated. Two barges were berthed on the same side of the canal as them, so decrepit they could have been mistaken for derelict, if it hadn’t been for the peelie-wallie-looking family glimpsed through the windows of one, and the skipper of the other halfheartedly scrubbing his deck. With a guilty air, he pretended not to notice them as they passed.

As legitimate trade had dwindled, so the smuggling of black-market goods had flourished along the canal, although that wasn’t why Dreghorn and Ellen were there; in piratical terms, it was hardly

Treasure Island. They walked a little further, scanning the long grass at the side of the path. The handlebars of a motorcycle came into view, the grass around them swaying and rocking, although there was little breeze. Dreghorn stopped, put his finger to his lips, and pointed.

Two pairs of feet, one male, one female, protruded from the grass at the edge of the path; the woman’s on the bottom, splayed awkwardly, kicking and struggling, the man’s on top, toes down, scuffing the earth to gain purchase. The man rolled away suddenly, revealing the black-and-white sheen of his spats—completely inappropriate for Scottish weather, but easily identifiable as the shoes the suspect they were seeking was described as wearing.

Dixon “Dixie” White: robbery, assault and battery, and, looking increasingly likely, manslaughter, if not murder.

The case had dragged on with painfully slow progress for almost a year. It wasn’t an investigation Dreghorn was particularly keen on, but Chief Constable Sillitoe had insisted that he take charge, as it was an important test of the new Fingerprint Department, recently set up to replace the ink-spattered, index-free shambles of the previous regime.

The first robbery had been at the Kingsway Cinema in Cathcart Road, May 1932, with several nights’ takings swiftly and efficiently snatched at around 1 a.m., while the watchman enjoyed a supper break that ended up costing him his job. Sergeant Bertie Hammond had succeeded in lifting a full set of fingerprints from the safe, but there was no match with the paltry samples in the files. Hammond, whose eagle eyes Sillitoe had brought with him from Sheffield, dispatched copies of the prints to Scotland Yard in London. Again, no match.

Four more picture houses were robbed over the following months, before the bandit moved further afield with the same modus operandi—to Paisley, Greencock, and Troon. At every crime scene, prints were discovered, sometimes fragmentary, but all matching.

The bandit had to be young, fit, and something of a daredevil, due to the rooftop acrobatics many of the crimes demanded. He was likely to be a bachelor of no permanent abode, moving freely from district to district and spending time in each as he planned his heists. Beyond that, and the fact that he was a fan of the pictures, they had little to go on.

The case had become more serious on 25 March this year, when the night watchman of the King’s Cinema in Sauchiehall Street was found unconscious at the bottom of the stairs that led from the foyer to the auditorium, presumably after encountering the cinema bandit. The man’s skull was fractured; doctors feared the worst.

Two days later the manager of the Blythswood Hotel had contacted CID about one of his guests, a young man named White, resident in the hotel for over a week. On check-in, he had asked to be awoken each morning at eight sharp with a cup of tea, a service the hotel charged threepence for. Each day, along with some risqué flirting, White gave the waitress who served him the tea a half-crown tip.

This largesse aroused the suspicions of the spendthrift manager: White didn’t appear to work, but wasn’t short of money and, in the midst of the Depression, had just bought a new Matchless Silver Hawk motorcycle, the roar of which disturbed other residents.

Dreghorn’s informant Bosseye, a skelly-eyed bookie who boasted that he could see in opposite directions at once, asked around his punters and learned that White was originally from Partick, but had gone off to London in 1927 to make his fortune.

He had recently returned, sporting spats and fancy suits, and was often to be found standing his old pals drinks in the Windsor, the Hayburn Vaults, or Tennent’s Bar. By all accounts, his newfound gallusness rubbed them up the wrong way, but drinks were hard to come by in the Depression, so if you had to suffer some shite patter to get one, so be it. Patience was wearing thin, though, because of White’s habit of tempting the local girls with a flash of his wallet and a ride on his motorcycle.

Dreghorn had recruited WPC Ellen Duncan to question the Blythswood waitresses, figuring they’d be more likely to open up to her than a hardened thirty-five-year-old detective. It hadn’t taken her long to establish that White was tipping all the female staff generously and was—unknown to each of the others—“stepping out” with three of them. Where did they go on these romantic excursions? The pictures.

Hammond had been keen to get a sample of White’s prints, but without more substantial evidence, there was no legal means of forcing the suspected burglar to hand them over, although Dreghorn made a couple of illegal suggestions.

Sillitoe snapped testily, “I know you Scots have a reputation for being tight-fisted, but we can’t arrest a man simply because he’s a generous tipper.”

“Agreed, sir.” Hammond cocked his head conspiratorially. “But we can arrest the teacup.”

Ellen had collected the potentially incriminating china from the Blythswood’s manager that morning, but by the time identification was confirmed, the dapper White had left the hotel, scooting off on his bike.

Dreghorn stationed a pair of uniformed officers at the hotel, in case White returned unexpectedly, then drove to Partick, taking Ellen along, somewhat against regulations, in gratitude for the good work she’d already carried out. They scoured the pubs and cafes White was known to frequent, but animosity toward the police won out over ambivalence to the motorcyclist and they met only a stony-faced silence.

Finally a little fellow slinked out of the Hayburn Vaults after them. Glancing over his shoulder, he whispered, “If I did know where he was, what’s in it for me?”